In the last six months, the American Library Association has seen a spike in book challenges and bans in both school and public libraries, mostly targeting books that center on race and LGBT identity. At the end of 2021, Wake County experienced its own high-profile censorship controversy.

Gender Queer, a graphic memoir about author Maia Kobabe's journey towards identifying as transgender, was removed from Wake County Public Library in December after complaints that it was pornographic. The removal was met with outrage from some in the Wake County community, including an open letter from librarians in protest. In response, WCPL announced on January 10 that they would return Gender Queer to the shelves and work on revising their removal policy.

In October of last year, a video surfaced of Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson's remarks calling books about LGBT identity “filth.” When many North Carolinians expressed outrage, Robinson defended his comments and targeted three books specifically for removal: Gender Queer, Lawn Boy, and George, which he described as “pornographic” and inappropriate for schools and libraries.

Last fall, Wake County residents complained about these same books. Jessica Lewis spoke on behalf of a group of parents at a December Wake County school board public meeting.

“Why do our kids have access to this obscenity in our libraries? Who is going to be held accountable for this?" Lewis asked as she quoted segments of the books. "No matter what gender you are, these books have no business being in our libraries.”

Nine mothers filed a criminal complaint against Wake County Public School System in December. Among them was Julie Page, who called the books “R-rated, if not X-rated,” and said that having them available in the public school system was a violation of state and federal statutes protecting minors from obscenity.

Wake County librarian Megan Roberts, who is also a member of the American Library Association, says that it’s difficult to accept the argument that these complaints aren’t about race and LGBT identity when they most often target books with those themes.

Book challenge boom

Although book challenges and bans have a long history, a representative of the American Library Association's Office of Intellectual Freedom said they saw an "unprecedented" number of book challenges in the fall of 2021. From September 1 to December 1, the ALA received 330 book challenge reports, more than twice the number of reports for the entire year of 2020.

Six of the top ten most challenged books in 2020 were about racism, books which not coincidentally were also on many of the antiracist reading lists being passed around that year. The complaints described these books as "divisive" or "containing an anti-police message."

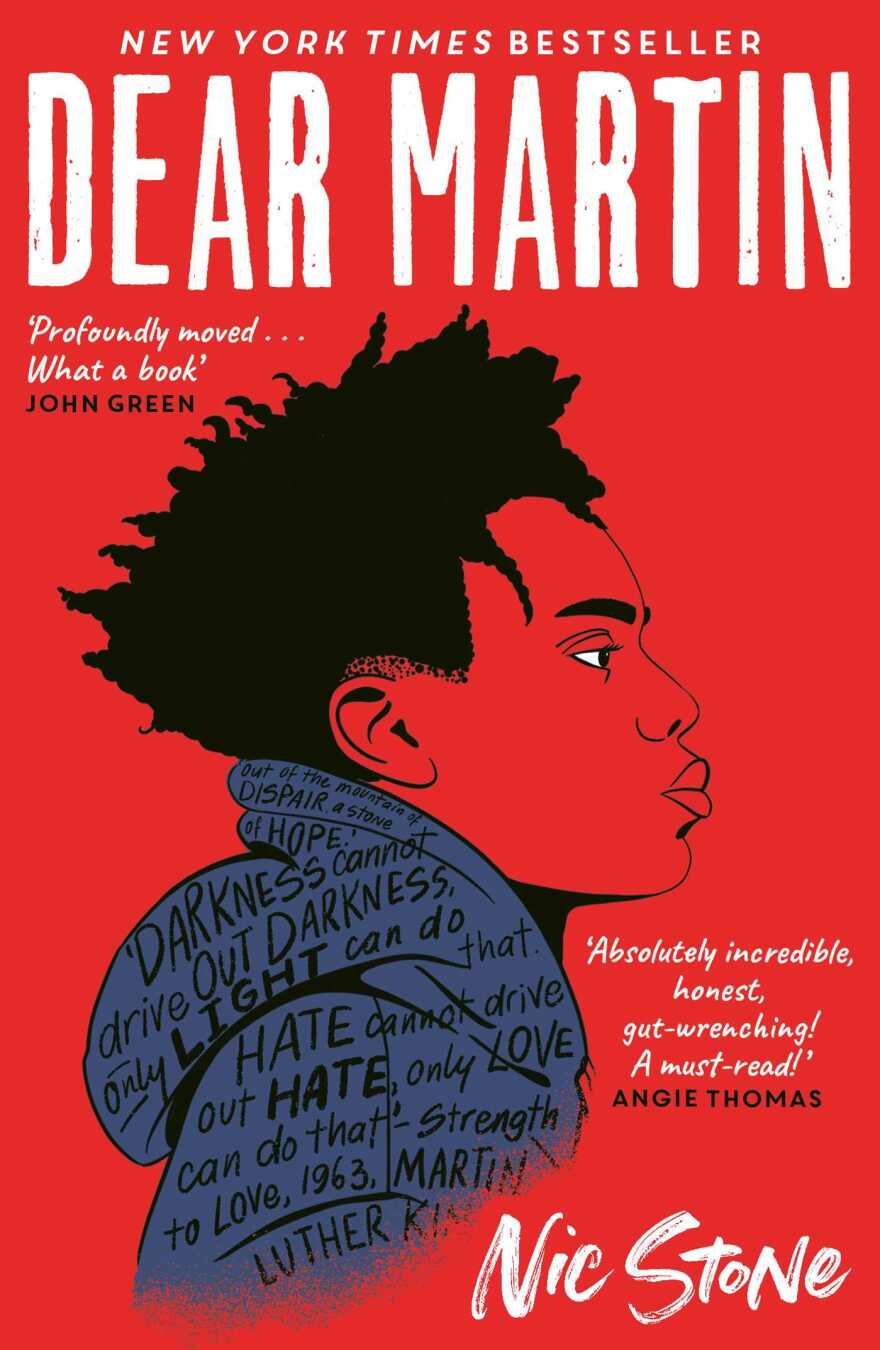

Last Thursday, Maus, the acclaimed graphic novel about the Holocaust, was banned by a Tennessee school district. In North Carolina, in just the last week, Dear Martin, about a Black student in a white school who writes letters to Martin Luther King, Jr, was pulled from assigned reading at a high school in Waynesville after a complaint. George, a children's novel with a transgender protagonist, was unsuccessfully challenged in Moore County.

Richard Price, associate professor of Political Science at Weber State University in Utah, is an expert in censorship, particularly through book challenges, and runs a blog called Adventures in Censorship. They agree with oft-banned children’s author Judy Blume, who has often said that book challenges were driven by fear.

“When it comes to representations of people of color and civil rights concerns, or queer inclusion in literature, the attack is contextually about something else,” said Price. “They dress it up and claim it's about swearing, or the book has sex in it. But in reality, most of this is driven by … parents who don't like seeing their world change.”

Price sees this recent uproar as a confluence of three things: the nationwide moral panic about the myth that Critical Race Theory was being taught in schools, which picked up around 2019 with the release of the 1619 Project; then, the pandemic causing more tension between parents and schools with shutdowns, online schooling, vaccine and mask requirements; and in 2021, a return to in-person school in most districts.

"Representation is really important. And it's a way to understand yourself and those around you. And I think that matters, and everyone should be able to see themselves in a book at the public library."Megan Roberts, Wake County librarian

The ALA has said that restricting access to books is a violation of minors’ First Amendment rights, but Price said that it’s not always simple. In the 1982 Supreme Court case Board of Education v. Pico, a plurality of judges ruled that a politically motivated removal of books violates free speech rights, but that removal based on grounds of “pervasive vulgarity” or educational suitability” would be constitutional — and that leaves room for interpretation.

Still, Price feels that schools and libraries have a responsibility to accurately represent the truth. “There's no such thing as neutrality between inclusion and exclusion,” said Price. “So if you're telling me that I have to be politically neutral in a classroom, and that means I can never talk about LGBTQ people or issues, that's not neutral, that is exclusionary.”

Megan Roberts, the Wake County librarian, doesn’t believe that it’s the job of librarians to protect readers, no matter their age.

“There's definitely something in every library that will offend any reader, any person. But that's one of the reasons I think it's so important to have books on a diverse array of viewpoints,” said Roberts. “Representation is really important. And it's a way to understand yourself and those around you. And I think that matters, and everyone should be able to see themselves in a book at the public library.”