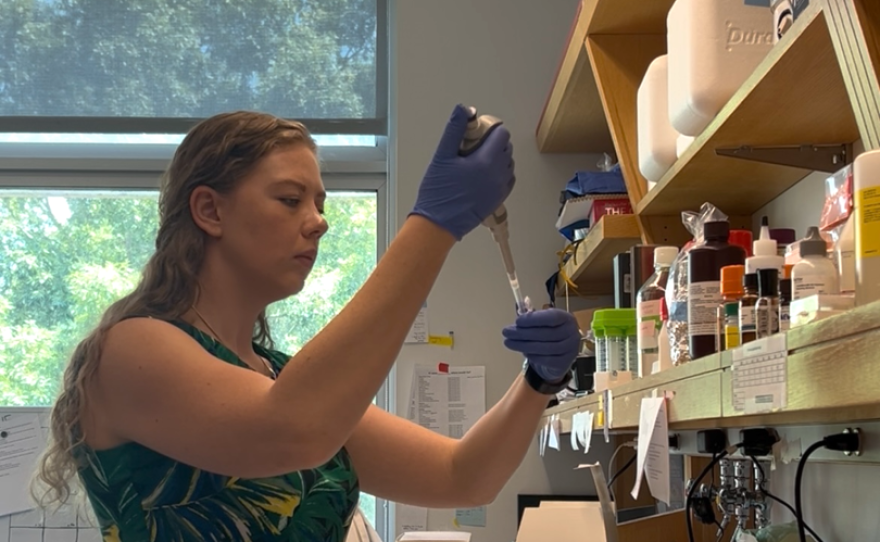

Helen Rueckert grew up in a small town in mid-Michigan and has always had a love for science. It wasn't until she was selected to attend a special STEM high school for rural students, however, until she truly saw it as a career.

From there, she earned a biochemistry degree at Temple University in Philadelphia and took a two-year hiatus from school to conduct research full-time. In the middle of the pandemic, she decided it was time for her to return to attain her PhD.

Five years later, she's now nearing the end of her studies at Duke University and is set to graduate early. But for the first time, she's having doubts about her path.

"I kind of wish some things had gone wrong at points in time, so I knew I at least have another year or year and a half before I could even think about graduating," Rueckert said. "Which is, I'll say, a terrible way to feel about something. You should be excited about being able to finish something in a faster timeline."

Rueckert's worries aren't due to a lack of drive or direction – she's already landed a postdoctoral research position in her home state to study muscular injuries. It's supposed to start in January, but Rueckert is concerned impending federal funding changes will cost her the opportunity.

"What if that lab's funding gets cut?" Rueckert said. "Or what if they have their grants paused and then people have to be laid off? And now I've signed a 12-month lease, and I don't have a source of income."

Universities across the country are bracing for the impacts of billions of dollars in federal funding cuts. They are taking a multi-pronged approach to prepare for the budget hit, from spending less on campus projects and lowering admissions for PhD students to freezing hiring and offering voluntary buyouts.

The ramifications of federal changes are being felt throughout the higher education ladder. Faculty are losing research grants. Students may lose access to federal loans. But one group is set to be particularly hard hit – young scholars just beginning a career in research.

Maren Wood is the CEO of the Center for Graduate Career Success, an organization that provides advising support to nearly 80 universities, including several in North Carolina. She's predicting this will be one of the worst job markets for graduate students in a generation.

"As people's grants have been cut or paused or reviews have been delayed, there literally is no money to pay postdocs," Wood said. "And so, what we're seeing is that people who are in the middle of their postdoc – so maybe they're one year into what should have been a three-year postdoc – suddenly there's no money left to pay them and they are being given notice. They are being let go by the institution."

Federal funding uncertainty isn’t just affecting scholars entering postdocs, but it's also causing a tough market for those finishing their positions and entering academia. Wood said in a normal year, about 10-15% of doctoral graduates in STEM earn tenure or tenure-track positions.

"I cannot imagine there are many universities that are going to put out job ads for tenure-track positions," Wood said. "We know that there are hiring freezes. We are hearing from people about budget cuts, reduction in budgets across the board. There's just so much uncertainty."

In North Carolina, Duke and NC State universities have frozen hiring of new faculty and staff. And as first reported by The News & Observer, the UNC System President has directed the state's other 15 public university chancellors to approve all new hires.

This worries postdoctoral researcher Susanna Brantley, who will soon enter the faculty job market.

"You could wake up to a news story next week that your university, all of their funds have been cut," Brantley said. "That's happened at a couple of institutions now. You just don't know if your institution is next. And that makes any institution feel uncertain, I think, about doing stuff."

Brantley's dream to become a research faculty member is 15 years in the making. It started in her AP Biology class back in 2009, when she first fell in love with science. She later earned an undergraduate and master’s degree at Emory and her PhD in developmental biology at Stanford.

She's been researching cell biology as a postdoc at Duke for the past five years. Her work is funded by a prestigious National Institutes of Health grant reserved for early career scientists. It also comes with three years of funding beyond the postdoc for Brantley to start a lab of her own.

Brantley said when the NIH awarded her the grant, it was the first time she really felt like someone wanted her to do her research.

"You are always sort of like 'well, my idea isn't that great or what is what I'm doing matter that much?'" Brantley said. "But then you get $750,000 to start your lab and you're like 'okay, maybe I am good at it, they think this is important.' So, you get excited."

"Now, it's very different," Brantley continued. "I don't know if I basically have to accept the fact that it could just be over."

In order for Brantley to access the next level of her funding, a university must hire her as a tenure-track faculty member. If she doesn't find a position by July 2026, it all goes away.

And for Brantley, it's not just the money that's at stake.

"It's the promise that I could start this new research group," Brantley said. "That my research group would do something cool for the next 15 years. All the students that I could see myself training. It's like that promise is also up in the air."

The federal funding threat has already changed the future of science. Beth Sullivan is an associate dean of research training at Duke who oversees more than 600 students in the School of Medicine.

This year, Sullivan's department curtailed its PhD admissions by 25%. She said Duke wasn't the only university that had to make that decision.

"I was constantly in contact with my counterparts at other schools and some of them rescinded 25% of their offers, 15% of their offers," Sullivan said. "So young people who are trying to take the next step in their career, what has come down from the federal government has had this huge ripple effect for the future of a lot of individuals across the nation and also internationally."

Sullivan said it is even more difficult for international students, who are facing mounting barriers from the federal government.

"27% of the students that we accepted for this fall class are international and there are a lot of question marks around that," Sullivan said. "We don't even know if they're going to be able to get here. The domino effect is even extending beyond our borders and it's impacting not just the national pipeline for research, but the international pipeline for research."

For PhD student Rueckert, the Michigan postdoc opportunity is her ideal appointment. The lab's focus fits her research interest and she'd finally be able to live near her family again. However, she's been brainstorming contingency plans in case her position falls through.

One of the most recent ideas she has started to think about is pursuing a postdoc outside of the United States.

"Whether it's the sort of general uncertainty or those very scary things where individual universities could be targeted, to just sort of not have to live with that," Rueckert said. "If you were in a foreign place, a different country, going to do research abroad – it's much less likely that you would have those worries."

Rueckert wants to someday run her own public research lab, similar to Brantley's dream.

Brantley said she's not sure what her future will look like if she isn't able to get a tenure-track position.

"Probably what I would do is teach or see what other sort of jobs there are?" Brantley said. "I don't know though, I haven't looked. I haven't looked around. I'll worry about that at the end of the year. I think I'll have a better idea in December of what the outlook is going to be. I can't really, I don't have time to think about anything else than it working out."

Both Brantley and Rueckert are taking a 'wait and see' approach until the final federal budget passes. They're hoping public support for research turns things around by the fall.

"This is a very, very unfortunate position to be in, but also we're all in science in this position," Rueckert said. "I still have my day-to-day things that I have to accomplish here. So, I can't be totally paralyzed with all of that in between unease, because I have things I have to do here."

WUNC partners with Open Campus and NC Local on higher education coverage.