Death is a taboo topic. Acknowledging it feels like an admission of defeat — that there is no hope left. But in the face of a pandemic, death surrounds us.

And the way we process death has changed as we try to prevent the spread of COVID-19 with social distancing and stay-at-home orders. Funerals are being canceled and postponed. People are dying alone in hospital rooms, their loved ones barred from visiting them. On this installment of Embodied, host Anita Rao examines how the coronavirus pandemic strains the death care industry and interrupts personal grief processes.

''They are left alone in their grief — through no one's fault. I have a friend who lost a loved one. I would dearly love to sit with her. That's it. And we can't do that.'' -Deborah Lewis-Smith

Tanya Marsh, a funeral and cemetery law professor at Wake Forest University, joins the conversation to explain how the death care industry is overwhelmed by the pandemic. Marsh is also the host of the podcast Death et seq. Nina Jones Mason explains how funeral homes are adapting to serve the needs of grieving families, while maintaining social distancing. She is a fourth generation funeral director with Ellis D. Jones and Sons funeral services in Durham. And Dr. Raymond Barfield of Duke University Medical School shares his expertise on palliative care and grief processing. He is a pediatric oncologist and palliative care physician at Duke Health. He is also a professor of pediatrics and Christian theology in Duke’s Medical School and Divinity School.

We also hear from Marcus Wilson, a travel nurse from South Carolina who volunteered to work in a Bronx hospital treating COVID-19 patients. He describes watching patients die alone, but also how messages of appreciation for hospital workers keep his spirits up. Crosby Lupton, a Harnett County native, shares how her family decided to delay her father's memorial service from March 21 to later this summer. She is using the newfound time to grapple with her complicated relationship with her late dad, as well as personalize a playlist for his funeral.

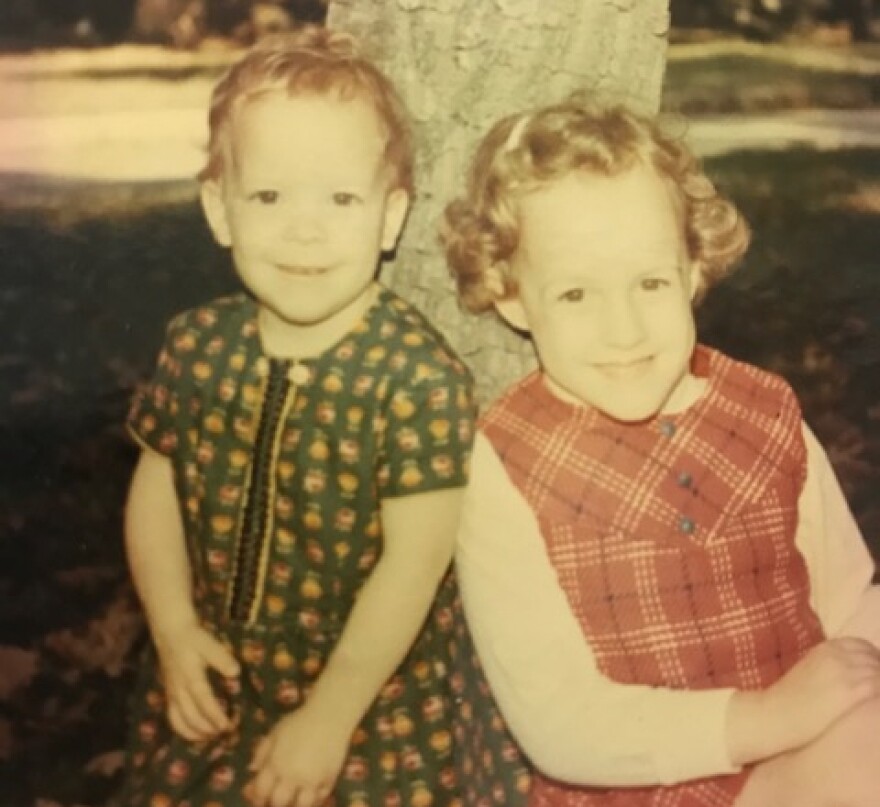

Deborah Lewis-Smith of Asheville talks about how hard it is to grieve without physical touch. And Melissa Swarbrick of Pinehurst shares the story of how her younger sister passed away of complications related to COVID-19 earlier this month. Her sister, Kathleen, started the Deaf Studies program at Westchester University.

Interview Highlights

Marsh on the relationship between public health concern and grief in death, highlighted by the coronavirus pandemic:

The funeral is the way that we express grief and process grief. And it's also a method leading to, to body disposition. But what we've seen in New York, because of the challenges to the whole system based on the sheer number of bodies it's having to deal with, is we're bifurcating those two things. So people can't be with their loved ones when they're dying, as the gentleman in the clip described. They can't spend time with the body after death. They can't do a traditional viewing, they can't do a funeral. The funeral homes are for the most part closed because they've run out of refrigerator space. And some have converted their chapels into temporary morgues — in some cases, turning the refrigerator or turning the air conditioning down as low as possible, which is still way too warm for that purpose.

''It's been hard to not have closure, but it's also given us the space to like, really think about how to honor my dad.'' -Crosby Lupton

Jones Mason on the importance of grieving in a community after death:

I think for a while, people haven't really considered the need for community during grief. We've kind of pulled away saying: Oh, well, we may have a service or we may not. Or people say: Oh, just throw me away. I don't need all of that or whatever. And then I think what people are realizing now about the funeral industry, that it is about the deceased, but it's for the family. And to be able to come together and bring that joy to other people, you know, is important, I think until you're told you can't do it.

''I kept thinking: Oh, tomorrow something great will happen. They tried everything- different antibiotics, and with everything they gave her she actually got worse. And we never got to talk to her again.'' -Melissa Swarbrick

Dr. Barfield on the importance of the serenity prayer and grace in processing these difficult times:

If we can recognize the difference between things that we cannot change, no matter how much energy we put into them, and things we can change and start asking a different kind of question — we can at least begin letting some light into the room. And so that's one thing that my residents probably get tired of hearing me talk about the serenity prayer before I walk into the room to be with a family who's wrestling with something difficult. …

And it is all too easy to look backwards and to think: Maybe I should have done this. Maybe I should have recognized the signs. Maybe I should have said something different. Maybe I should have spoken more quickly. … On and on. But for the most part, we make the best decisions that we can. And in this COVID pandemic, if you look at everything from top leadership, to hospital leadership, to the ways that families are trying to respond to adversity, we're having to make it up as we go. None of us have experienced this kind of worldwide shutdown and crisis. And so I think there is more than enough room for a sense of grace towards ourselves and towards others as people genuinely try to do the best that they can in a confusing, bewildering time.