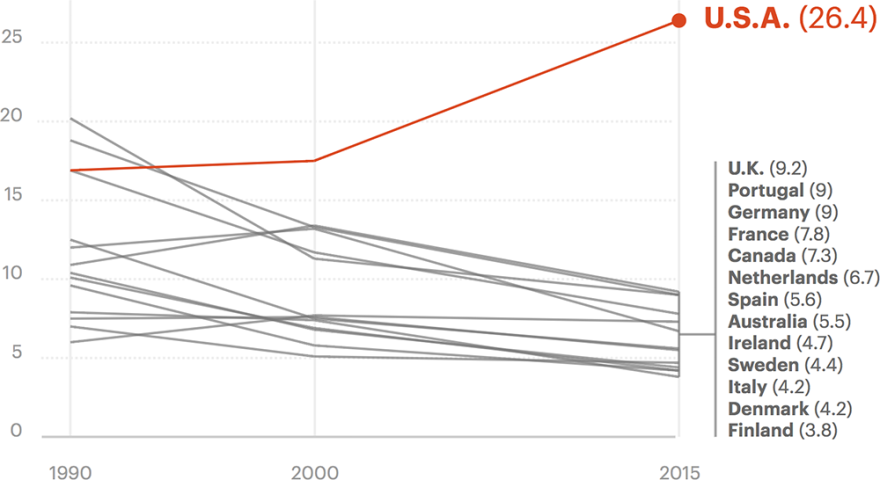

Childbearing in the United States is more deadly than in any other developed nation. Despite medical advances over the last few decades, the number of reported pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. continues to steadily increase.

Host Anita Rao tackles the maternal health crisis in North Carolina on this installment of Embodied, our series about sex, relationships and your health.

One birthing center remains in the region west of Asheville. Pregnant people in Cherokee County are facing higher costs in hospitals across state lines or driving more than 60 miles to the closest in-state option. Lilly Knoepp of Blue Ridge Public Radio shares her reporting about how travel distance affects health outcomes.

Keisha Bentley-Edwards also joins the conversation to talk about the reasons and solutions for persistently worse healthcare for black people during pregnancy. Bentley-Edwards is an assistant professor at the Duke University School of Medicine. And Dr. Alison Stuebe outlines the ways Medicaid and other insurers could improve overall health outcomes by expanding prenatal and postpartum care. Stuebe is an associate professor in the department of maternal and child health and the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS:

Knoepp on travelling to deliver:

It might be easier for people to get to Tennessee or Georgia. There are a couple thousand women who are of the age that they can have babies out there who now are [having to go] out of state. … There are issues with Medicaid transferring across state lines, dealing with different insurance across state lines, all of these, you know, artificial barriers as well as the physical barriers of the mountains in these drives that people are having to make while they're in labor.

If we want rural hospitals to stay open in North Carolina, one very simple policy fix is to enact Medicaid expansion, because then hospitals would be able to afford to operate. - Dr. Alison Stuebe

Stuebe on healthcare deserts:

When rural maternity hospitals close, there are more births happening out of the hospital. … Folks can come to an emergency room and have their baby, but that's clearly not optimal. The staff there isn't used to doing births. They're not trained for that. And certainly, if there's a problem where one needs a C-section or needs pediatric help to resuscitate a sick baby, those services aren't in a small hospital without a labor and delivery unit. So that's riskier for everybody involved.

Stuebe on the financial loss from Medicaid reimbursements:

Pregnancy care for a privately insured person — for all the prenatal visits, the birth and the postpartum care — the reimbursement is about $3,000 to the doctor who provides all that care. For a patient on Medicaid, it's about $1,350. … That leads to many practices saying: We're not going to take Medicaid patients, or we're only going to take a certain number of Medicaid patients because we can't afford to be paid such a low reimbursement rate.

As a black woman, oftentimes our advocacy is perceived as having an attitude or being misguided, and not really being acknowledged as being experts on our own body. - Keisha Bentley-Edwards

Bentley-Edwards on addressing racism in pregnancy care:

Medicaid expansion is important, but we have to acknowledge that this is a racial issue, which means that you have to look at black women with disaggregated data. … To figure out the things that need to happen to support black women, we have to talk about toxic stress, we have to talk about domestic violence, we have to talk about employment discrimination — not just when you're pregnant, but beforehand.

View this post on Instagram Today on #EmbodiedWUNC... Why is childbearing in the US more deadly than in any other developed nation? A post shared by The State Of Things (@thestateofthings) on Feb 20, 2020 at 1:58pm PST