They buried my dad this week.

Normally, I'd say "we" buried him. But this is nothing like normal.

I was 1,300 miles away, working remotely, at my dining room table.

My sister, her husband, their son? They stood in a church cemetery in Maryland, socially distanced from the pastor, and the grave itself.

My brother and his wife were in the grass on the other side. So were another nephew, and a niece.

And my other brother and his wife? They left separate ends of their house, drove separate cars. At the cemetery, he couldn't do more than crack open his car window. Quarantined.

Ten people. One funeral. A pandemic-sized hole in our hearts.

See, Dad had COVID-19. They tested him Thursday, April 9, the day his liver gave out, the day half my family made a final visit. He died April 10. The results came back a day later. Positive.

I'm a journalist. I'd read plenty of stories about nightmares in nursing homes. About the horrors of a loved one dying alone, of the daughter waving through a window at a parent, of the brother left to grieve long distance.

Then it happened to me.

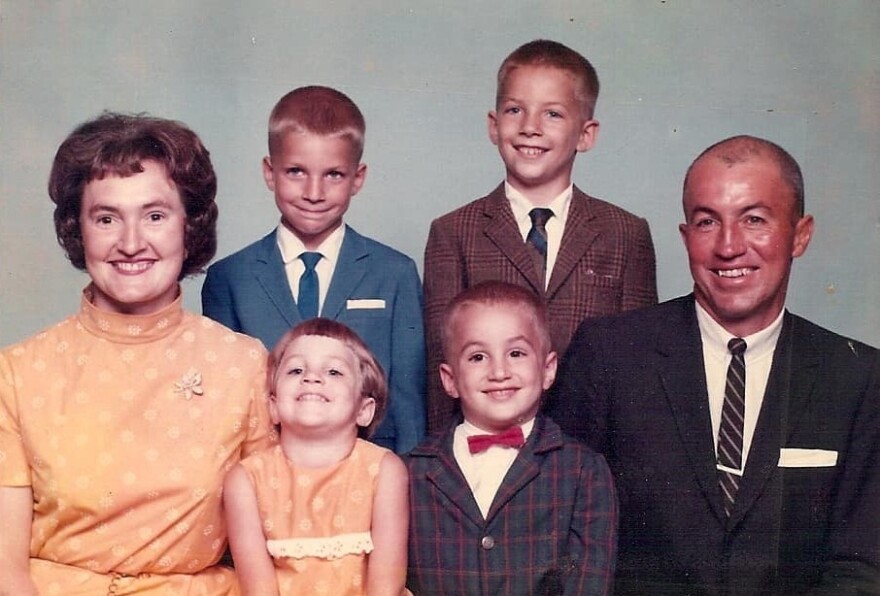

I'm Richard Jr., the oldest of four. He was Richard Holter Sr. Dick, to his friends. A dairy farmer who turned 92 last month, the day before St. Patrick's.

Time of death last Friday: 3:45 in the morning. Milking time.

In our family, he was always the quiet one.

The one who trudged out to round up the cows before dawn for three-quarters of a century on the farm he continued to run until his 70s. The one who spent more than a decade wheeling the love of his life,and later his dear friends, around the retirement center. The one who was fiercely loyal to the Maryland Terrapins — and whom I accompanied to ACC basketball tournaments for 30 straight years. The one who loved nothing more than sitting back with a grin while his kids, his grandkids and then his great-grandkids chattered away at Sunday dinner.

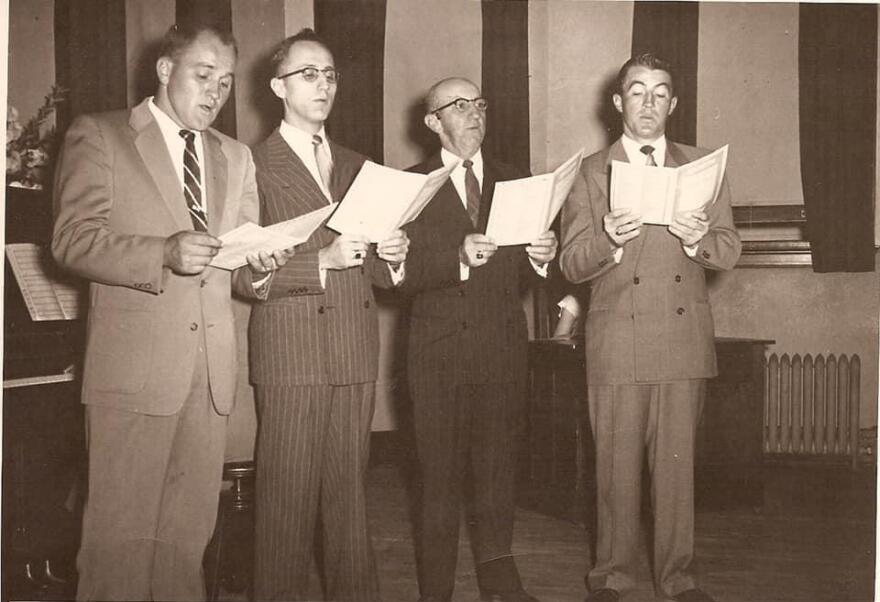

A man of deep faith and a clear tenor voice, whose quiet strength won't be forgotten.

The last few weeks, day after day, it's been so easy to get lost in those numbers – the confirmed cases, the ventilator count, the deaths.

My dad would have appreciated the close attention we're paying to the numbers. He loved sports, loved to check the box scores in the paper every morning, loved to repeat 'em on the phone later that day, even if you'd read the same box score online the night before.

The thing is, today ... thesenumbers? Every one is one. Every one is a Dick Holter.

Way back, we're Norwegian Germans. A little stoic, not exactly emotional. Not a lot of tears.

On Sunday, I asked Alexa to play some background music. She obliged. As she always does. Then came this song.

525,600 minutes, 525,000 moments so dear.

525,600 minutes - how do you measure, measure a year?

"Seasons of Love" from Rent. A musical about AIDS, based on an opera about tuberculosis (La Boheme) arriving in the middle of a pandemic that killed my dad.

I grabbed my wife in a vicious hug. And I broke.

In daylights, in sunsets, in midnights, in cups of coffee

In inches, in miles, in laughter, in strife

In 525,600 minutes

How do you measure a year in the life?

For my dad, it would've been about 49 million 400 minutes. And not one of them wasted.

Rick Holter is vice president of news at member station KERA and a former supervising senior editor at NPR.

Copyright 2021 KERA. To see more, visit KERA. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))