With continued protests around the state of North Carolina to respond to police brutality and support the movement for Black lives, young activists are thinking about they can move conversation in their own communities. Maya Nair is a sophomore at UNC Chapel Hill. She produced this story for WUNC’s Youth Reporting Institute.

Arush Narang is a junior at Enloe High School in Raleigh, North Carolina. He'd never been to a protest before this year, but since May, he's been going to marches all over the Triangle.

"Yeah, like we've been, we've been chanting like the four names of people that have been killed by RPD: Keith Collins, Akiel Denkins, Soheil Mojarrad, Kyron Hinton…"

But at these protests, he noticed there weren't many people who looked like him: young people from the South Asian community. This is something I noticed too when I hit the streets this year to protest for the Black Lives Matter movement – I could only see a few brown faces. It made me wonder what my community is doing to show up for racial justice. My friend Roshni Arun has been wondering, too.

"Honestly, I haven't really seen that many South Asians take action, which I find pretty upsetting... Like, I see you guys going to parties… going to the beach, getting your nails done so why have you not been able to protest?"

Roshni is a 19-year old sophomore at Appalachian State University. This summer, we went to a Black Lives Matter protest together in Chapel Hill, but we had to lie to our parents. I didn't ask my parents because I was afraid they'd say no. I thought they wouldn't understand what protesting really is or why I need to go.

Arush was more direct with his parents but every day he went out to protest, he had to have a long discussion with his parents. Every time he left the house to protest, Arush had to negotiate with his parents, which meant doing ACT prep every day to be allowed to go. When we talked, he showed me his desk covered with ACT prep books.

"My parents are making me do right now are making me do ACT tests during a pandemic," Arush said. "Yeah, so pretty much yeah, that was my compromise like I would, I would like, take a test before I go to the protest and they'd be okay."

I can totally relate...it's the same with my parents - schoolwork and academics must always come first. After talking with Arush though, I realized I had never actually sat down to talk to my parents about why protesting is so important or why the Black Lives Matter movement affects brown people, too. So I decided to test it out. I sat down to talk to my mom.

One of the first things she brought up was a scene from a protest she saw on TV, with a young Black woman facing a line of militarized cops.

"Like, okay, my daughter is of the same age. What if she's there and that's how the police treat her? And I didn't like it," she said.

I did not expect to hear this from my mom - that as a mother, she feels that what the police are doing isn’t right. And she understands why me and my peers feel called to speak out.

"I think the next generation are more vocal about it. And I'm happy about that," she said. "The first generation, our generation still trying to figure out where they belong, whether they belong here. So they're, they're too busy doing that. But I think the next generation, they do feel that they belong here, and they're working towards it to make it home."

I was surprised to find out my mom appreciates my generation taking action. But I wanted to figure out why I didn't see South Asians from my parents' generation showing up to support Black lives. I asked my dad about it.

"They are more involved and interested in the betterment of their own lot," he said. "At the same time, they're more interested in, in mixing and in the local community. So that doesn't leave them a lot of time to participate in activism."

What my dad is talking about is assimilation. And assimilating into a culture saturated with anti-Black racism often means my community accepts those same racist ideas. We do this to gain the fake status of a "model minority," so that we look more "safe," thinking this would make us more deserving of the American Dream.

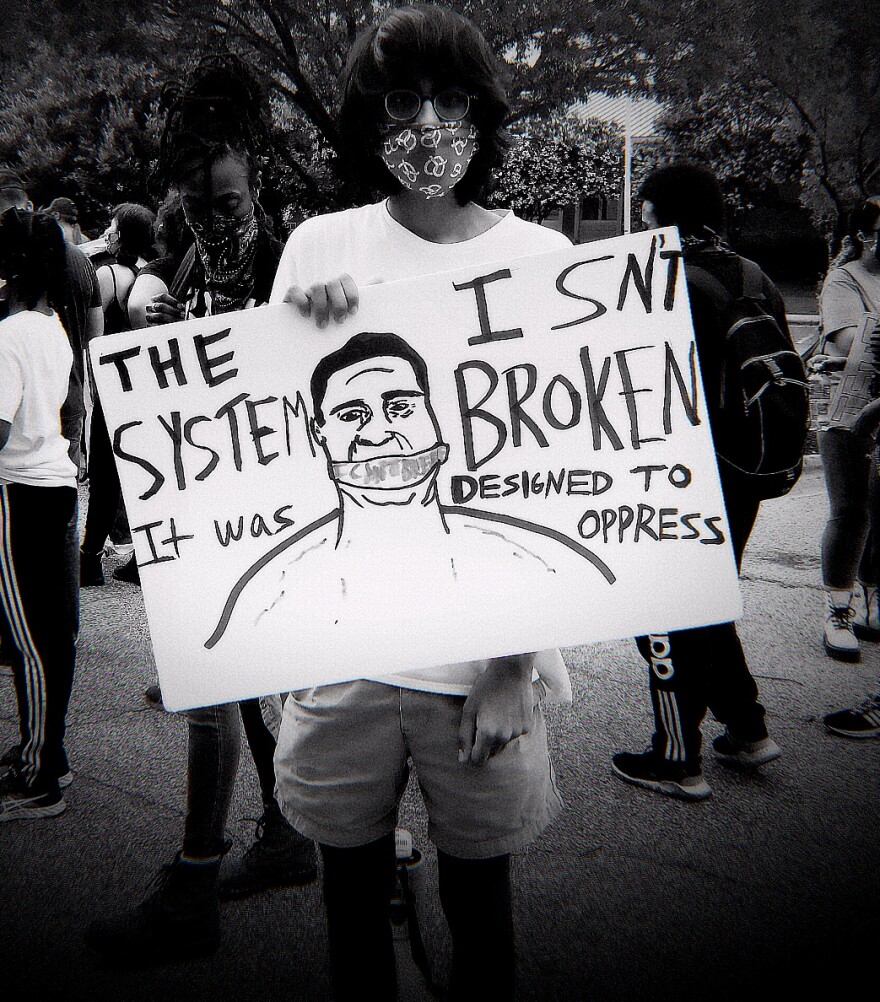

This was a tough talk to have with my parents, but I learned a lot from this first one. Turns out my parents do understand, to a certain extent, why I go to Black Lives Matter protests, and, you know, why it matters, which encourages me to have more discussions about race and injustice with them, like my friend Roshni who is using art to start conversations with her parents and neighbors about anti-Black racism. Over the summer, she drew a chalk mural of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery in her parents' driveway. But she had to talk to her parents first.

"I was a little nervous about asking them at first because, like, there is anti-Blackness in the South Asian community," she said.

Roshni says creating art helped her start the conversation. She was inspired by Emory Douglas, an artist from the Black Panther Party. To go with the mural, she made bowling pins that represent cops but their heads are pigs. With this art, she wanted to show how knocking over pins is not enough. Roshni believes that we need to dismantle the system.

"When I told my parents about the idea for the pig bowling pins, they were really hesitant… even though they were completely fine with me drawing on the driveway," she said. "When I told them about the pins, they asked me, What about the good cops?"

Questions like that are exactly why she created the art piece. To get her parents talking about the nuances of racism. It got her neighbors talking, too. Making change happen doesn't always mean going straight to social media, or grabbing masks and posters and marching down the streets. Activism can start small in your own community, and especially at home.

"I think that we shouldn't overlook the revolutionary potential of our neighbors, family and friends," Roshni said. "And I think that we should start with the circles closest to us.”

It can be hard, but these tough conversations are exactly what we need to get the South Asian community to become more aware of what is happening. And it’s our job as the younger generation to change how our community, as a whole, thinks and responds to oppression.