Hippocrates, the Greek father of medicine, wrote “all diseases begin in the gut.” He continued the line with the famous advice: “let medicine be thy food and food thy medicine.” New research confirms Hippocrates’ thinking, showing the human gut does much more than just process food.

The gut’s dense network of neural tissue serves as a conduit for communication between other microbial species and our own brains. Microbes in our gut help regulate serotonin, affecting anxiety levels and prompting that deep sense of satisfaction after eating your favorite meal. But the gut-brain connection is also a two-way road — stressful emotional events may increase the chances of Irritable bowel syndrome. Guest host Anita Rao talks with Ian Carroll, assistant professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Dr. Lin Chang of the School of Medicine and Vice-Chief, Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles about how the gut and brain communicate with one another and methods for treating abnormal communication, including fecal transplants.

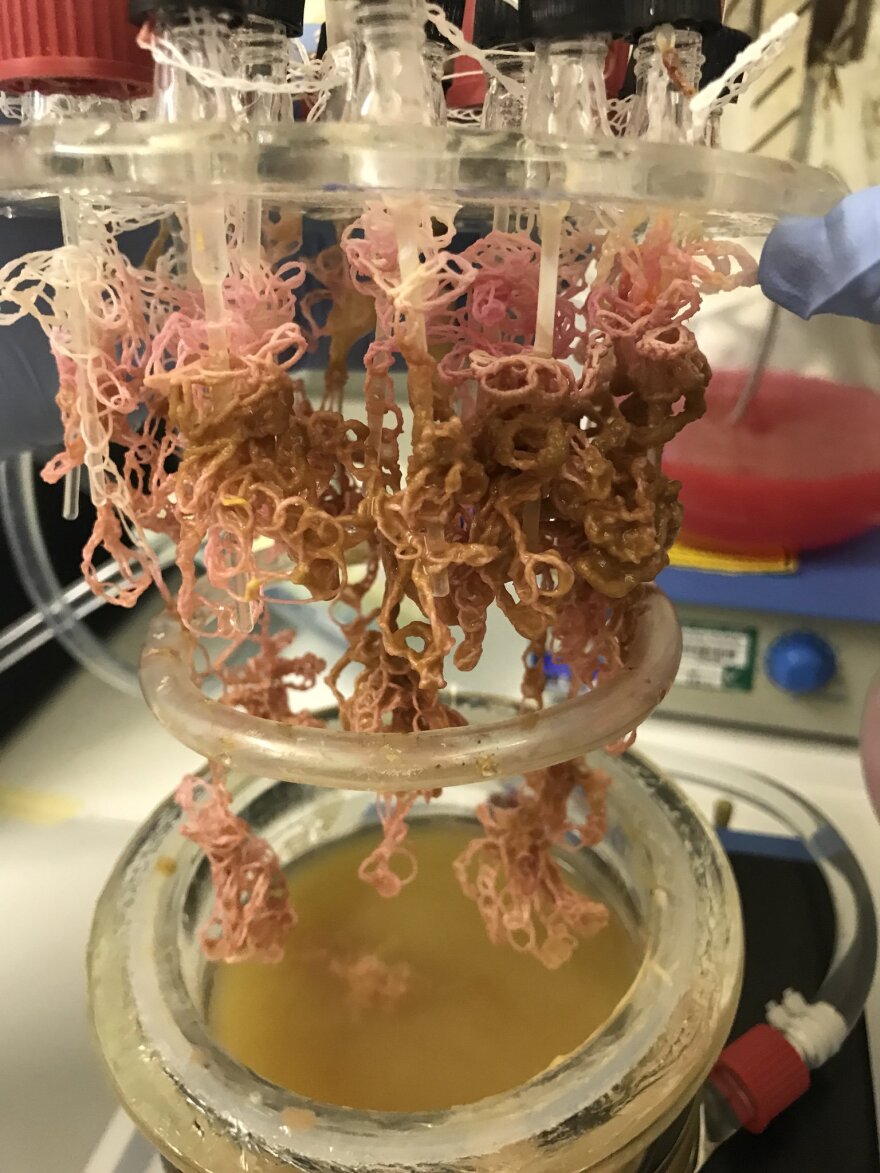

Also joining the conversation is Lydia Greene, a postdoctoral fellow at the Duke Lemur Center, who shares lessons learned about nutrition and health from studying the gut microbiome of our primate cousins. Finally, Anna Dumitriu reaches for the sublime in her creative interpretations of gastrointestinal infections. Dumitriu is an artist in residence with the Modernising Medical Microbiology Project at the University of Oxford and at the National Collection of Type Cultures at Public Health England. She is a visiting research fellow at the Brighton and Sussex Medical School.

This conversation is part of The State of Things’ new series “Embodied: Sex, Relationships and Your Health.”

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS:

Ian Carroll on our first encounter with germs:

When you're born, you're supposed to be sterile. And then you acquire your microbiota from your mother. Now, whether you're born via C-section or a natural birth, you're going to be colonized by vaginal microbes or skin microbes. … There's a series of ideas and thinking that whatever you're colonized with initially will impact what happens to you later on in life: obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome and many others.

Lydia Greene on what lemur poop can teach humans about our guts:

Lemurs are a fascinating system for studies of the gut microbiome. … They're our most distant cousins, so if we can understand what goes on in lemur poop ... that provides clues about our own evolutionary history with our gut microbes.

… Mammals, like humans, don't have the enzymes to break down cellulose on our own. We can't do it. … So microbes take your fiber, they eat it for you, they make short-chain fatty acids, you — the animal — absorbs the short-chain fatty acids, and those help you meet your energetic demands. And they also help promote health in a variety of body organs.

Lin Chang on communication between the gut and the brain:

It's really a highway system where there's signals from the gut to the brain and the brain back to the gut. … There are nerves that go from the gut, through the spinal cord to the brain. And that transmits sensations, information of how we're feeling. … Then the brain communicates back down to the body … and it could change how the immune function is in the gut and the motility and the sensation. So it's a very strong communication.

Ian Carroll on using a fecal microbial transplant (FMT) as a cure:

This is a technique that comes from ancient China, and it was called the yellow soup. So I hope nobody's having supper... It was fermented camel feces, or infant feces, and it was consumed to treat numerous types of illnesses.

What it's primarily indicated for right now is Clostridium difficile infection. [It’s a] recurrent infection, you can't get rid of. ... You take one FMT and 90% of people are ultimately cured. It goes up to about 95% after two rounds of FMT. This is really, really effective.

Anna Dumitriu on making art with microbes:

They are the most sublime organisms, they're these tiny things that kind of cover pretty much everything in the world. And they can kill us, they've changed society, they've changed the world.

… I work in the labs with the researchers. I've been doing this for about 20 years now, working hands-on with bacteria. So I've built up sort of a level of expertise.

… I think art has the ability to contain a complex idea. But in a multi-layered way, so you can be affected by the emotional, the sublime, the aesthetic side of it. ... Aesthetics cover things like disgust, as well, and horror and terror. All these things can be encapsulated in an artwork, and as you peel away the layers: how it was made, these other ideas, what are the media — because you can mix lots of media together — those sorts of things can give people a way into a kind of research that they wouldn't even consider looking at. Note: This program originally aired Aug. 22, 2019.