By her own admission, composer Florence Price had two strikes against her.

"To begin with I have two handicaps – those of sex and race. I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins," is how she began a 1943 letter to Serge Koussevitzky, the revered conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. She added later, "I would like to be judged on merit alone."

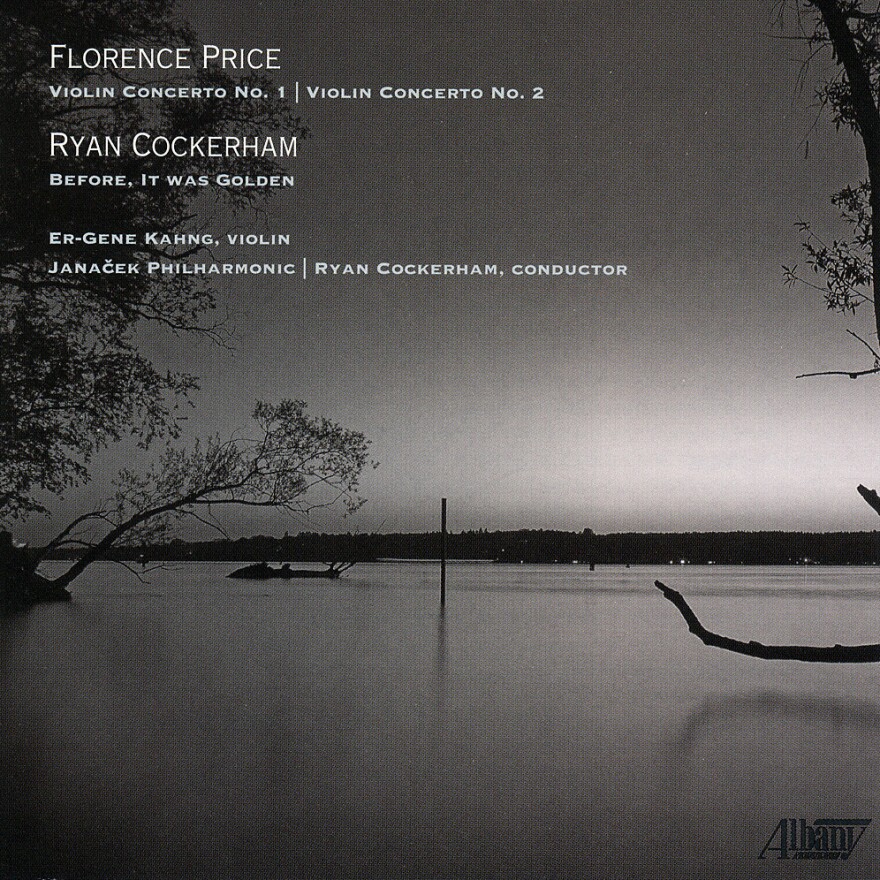

Koussevitzky never gave her music a chance, but along the way a few others did. Even so, her music is little known – and some of it was lost for decades – but now Price is finally receiving a little belated recognition. There's a profile in the New Yorker by Alex Ross and a new recording of two recently discovered Violin Concertos on the Albany label.

Price completed her Violin Concerto No. 2 in 1952, the year before her sudden death at age 66, just as she was set to explore career possibilities in Europe. The manuscript was never published and considered lost sometime after 1975, when Price's daughter died. The concerto, along with other music and personal papers, was discovered by accident in 2009 when renovators opened up an abandoned house Price once owned some 70 miles south of Chicago.

Unfolding over a relatively brief 14-minute span, the concerto opens with a sober orchestral introduction, pausing for a beat to let the solo violin make its honeyed, serpentine entrance. Violinist Er-Gene Kahng's tone, round and lustrous, is well-suited to the concerto's breezy melodic theme and dotted rhythm, which propels the music forward. Along with Price's harmonies – with their tasteful dabs of dissonance – the music is reminiscent of the sweeping, melody-driven American violin concertos of the 1930s by Samuel Barber and Erich Korngold.

Price grew up in Little Rock, Ark. and published her first piece in 1899. She enrolled at the New England Conservatory, where she studied with George Chadwick. Later, in Chicago, she earned a post-graduate degree in 1934. While working on her compositions, she wrote radio jingles, popular songs under the name "Vee Jay" and accompanied silent films at the organ. Later, she would write songs for contralto Marian Anderson, who sang Price's arrangement of "My Soul's Been Anchored in the Lord" at her historic 1939 Lincoln Memorial concert in Washington, D.C.

A breakthrough came in 1932, when Price's Symphony in E minor won Chicago's Wanamaker Music Contest. Along with the $500 award came a first performance. On June 15, 1933, conductor Frederick Stock debuted the symphony with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in a concert that included tenor Roland Hayes and music by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. The premiere secured Price her place in history as the first African American woman to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra.

Like her peers, William Grant Still and William Dawson, Price took inspiration from African American spirituals, although its influence isn't conspicuous in all her works. The Second Violin Concerto has distinctly American touches, but overall it's steeped in the European tradition, recalling the warmth and romantic facility of Antonín Dvořák. But Price's style isn't the only thread that connects her with the great Czech composer.

In 1892, Dvořák and his family set sail for the United States. By that time Price was five years old and had already given her first public piano recital.

Dvořák couldn't have known how prescient he was when, the following year, he told the New York Herald: "The future music of this country must be founded upon what are called the Negro melodies. This must be the real foundation of any serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States."

While Dvořák's pronouncement ruffled a few feathers in the music world, many others took the revered composer seriously. If he could have only heard Louis Armstrong, James Brown, Sun Ra, Kendrick Lamar – and the alluring music of Florence Price.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.