In many homes across the state, residents come home from work, turn on their lights, run their dishwashers and watch television or browse the Internet. They do all this without giving much thought to the electricity that courses for miles underground and through their house to power these devices.

Tom Hanes does.

Hanes oversees the Duke Energy natural gas-fired plant in Hamlet, near the South Carolina state line. At this 600-acre plant, cubic feet of natural gas are measured by the millions. From the top of the main generator, Ford F-150s in the parking lot look like Tonka toys.

“If we’re running this whole facility at one time, it’s anywhere from 2,000 to 2,200 megawatts per hour,” Hanes said on a partly sunny day in April. “One megawatt is about 800 to 1,000 homes.”

Doing some simple back-of-the-napkin math, that comes out to 2 million homes powered by this plant.

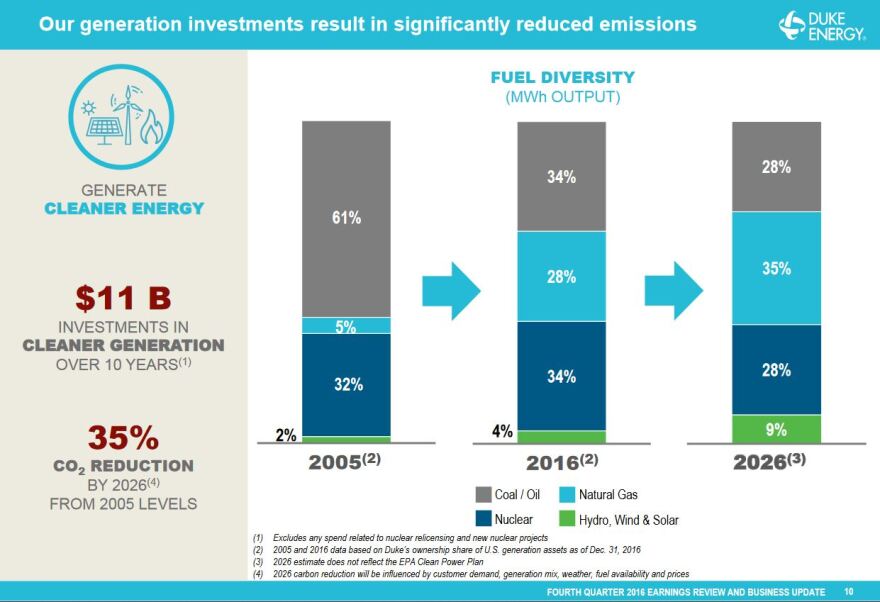

The Hamlet plant serves as a good case in point as Duke and other energy companies are charging toward energy production from natural gas. In 2005, natural gas comprised only 5 percent of total energy production. By 2016 that had already increased to 28 percent and it will grow to more than one-third of all energy production in less than a decade.

With advances in horizontal drilling techniques, energy production from natural gas has brought affordability and reliability.

However, natural gas also contains methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

Now, environmental groups have grown as concerned, and in some cases even more concerned, about natural gas as coal and warn that a continued reliance on this fossil fuel for energy production could push the earth’s temperatures to heights from which she won’t be able to recover.

A Shift Toward Natural Gas

Little more than a decade ago, the energy industry relied heavily on coal to produce the electricity to power the nation’s televisions, cell phones, computers and more. Coal comprised a full 61 percent of the fuel used by Duke Energy. This concerned environmentalists because coal emits carbon dioxide – CO2 – when burned, and CO2 traps heat. Therefore, the more CO2 in the atmosphere, the more heat trapped on the globe.

Then came horizontal drilling, a boon for the natural gas industry. In late 2016, Duke acquired Piedmont Natural Gas for $4.9 billion. Frank Yoho was Piedmont’s chief commercial officer and now heads the natural gas division for Duke.

“With the technology breakthrough of horizontal drilling, it really unleashed the resources in the shale rock formations. And basically gave our country really great access to natural gas supplies that weren’t accessible before,” Yoho said.

Yoho and others tout that natural gas burns much cleaner than coal. That’s accurate, but it tells only half the story. Natural gas is made up largely of methane. Before it’s burned, methane traps significantly more heat than carbon dioxide. In the first 20 years after release, methane traps a whopping 86 times as much heat at CO2, though methane stays in the environment for a shorter period of time than carbon dioxide. Even comparing the two gasses over a 100-year horizon, however, shows that methane is 20 times as potent as carbon dioxide.

So although natural gas burns cleaner, it contributes significantly to global warming when it leaks or vents out of the pipeline.

Here’s another sticking point to environmental groups. Energy companies use terms like leakage and venting, which portray a sort of drip-drip-dripping image. In reality, natural gas leaks out of pipelines in something that more closely resembles a geyser. By the industry’s own admission, it loses enough natural gas every day to power 6,000 fireplaces.

Duke’s Yoho said that he would rather not see gas escape pipes either.

“At the end of the day, our interests are aligned with the environment and are aligned with our customers. Because methane is not a waste product it's wasted product. So the less of that product that is wasted the better off for everybody,” he said.

While that makes sense intellectually, environmental groups wonder why so much gas still escapes pipes.

Lincoln Pratson is a Duke University professor and part of its Energy Initiative. He says age plays a factor. “A lot of the leakage that’s been reported on is through pipes that were laid down decades ago, and have developed these leaks and have not been upgraded,” he said. “And this is a real problem infrastructure-wise for the U.S. not only for natural gas but for water pipelines, for many types of pipelines.”

Under former President Barack Obama, the Environmental Protection Agency worked to install regulations to cap methane emissions, moves that the energy industry fought hard. While not referring to the Atlantic Coast Pipeline – which will carry natural gas from the deposits of the northeast down into the South – Duke's Yoho said that impediments to progress are the company’s biggest concerns.

“The biggest challenge for us today is building the necessary infrastructure to get our resources to our customers where they need it,” Yoho said. “There are some groups out there that don't want anything built for any reasons and it's very challenging.”

Questions About Supply

There is another concern about natural gas voiced by a small, but growing, corner of watchdog groups: They say the supply of natural gas is overestimated. Companies like Duke Energy have invested heavily in natural gas infrastructure and if supply projections indeed turn out to be overstated, these investments would hang around the industry’s neck like an anvil, with ratepayers ultimately on the hook.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration is part of the U.S. Department of Energy, and its projections are used across the industry. The EIA has for years shown significant natural gas deposits, especially in the Marcellus formation of Pennsylvania and New York.

However, a small group of geologists have called these estimates into question.

“The EIA, to put it politely, is very optimistic in terms of future gas production,” said David Hughes, an earth scientist with the Post Carbon Institute who has studied energy resources for decades. His work has been featured in the peer-reviewed journal Nature and elsewhere. “Industry and public utilities look at those forecasts and basically think the price of gas is going to be cheap forever. And therefore invest in gas-fired infrastructure. But from my work on the geology, that doesn’t make sense in the long run.”

Hughes has drawn his conclusions in part from looking at production, which has declined in the past 12 months. Extracting natural gas from some rock formations is easier than others. Drillers choose these so-called sweet-spot wells first to get the biggest bang for their buck. Hughes says that if production has slowed, the industry will turn to new wells, which he predicted won’t show the same return on investment.

To be sure, Hughes and others like him are in the minority, even among environmental groups, and Duke Energy’s Yoho said he has nothing but confidence in the EIA projections. “We’ve had about 10 years of being surprised on the high side,” he said. “Do things change? Are they exact? No. And things do change. But I am confident that they are good enough that we are going to have plenty of gas to meet the design of future power generation needs.”

Of course, a seemingly simple solution would be to simply generate electricity from renewable sources like solar or wind.

However, these present problems as well. While the costs of panels has dropped to a point that solar farms can be profitable, energy storage is still a high barrier. When consumers demand electricity, that is to say, when they turn on their televisions or fire up their washing machines, Duke Energy has to produce the electricity at that moment. So when the sun isn’t shining and wind isn’t blowing, consumers have two options: Own an expensive home battery, or use a fossil fuel.

Of course, consumers could go without electricity, though most people like to be assured they can turn on a hot shower on a cold January morning.

Natural gas offers a cheap and reliable alternative. The next decade promises big steps in renewables. But until then, natural gas will play a major role in the energy production.