Just as the coronavirus pandemic began its rapid and deadly spread across the United States, a well-known doctor named Dominique Fradin-Read told thousands of viewers tuning into an Instagram Live video that she had an answer: "one of the best ways to prevent and fight COVID-19."

It was April 2020. The virus had already killed 50,000 Americans, a number that has since grown to more than 200,000. And scientists were scrambling to find a safe and effective treatment — a search that continues to this day.

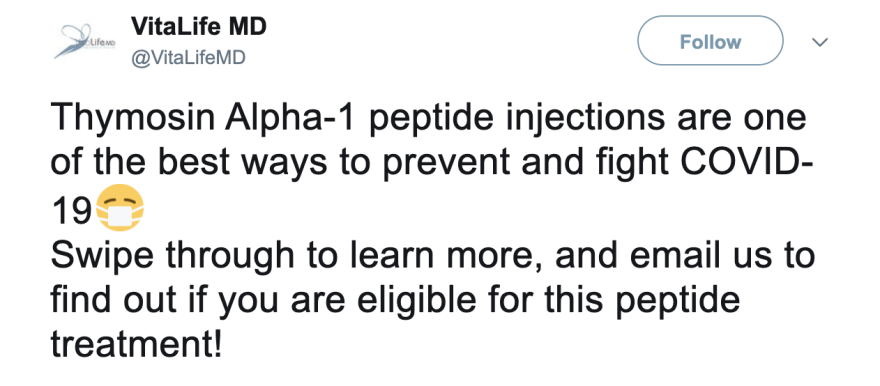

Fradin-Read is a prominent figure in the wellness community. She owns the medical practice VitaLifeMD in Los Angeles and helped formulate the "Madame Ovary" supplement for actor Gwyneth Paltrow's brand Goop.

This time, on Instagram, Fradin-Read was promoting more than just "wellness." In the face of a deadly pandemic, she claimed to have an "FDA-approved" medicine that worked like "magic." Fradin-Read made similar claims on her practice's Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts. If patients followed her advice, including getting regular injections of this drug, she said, "maybe the virus will not be that hard to fight."

Such claims were, at best, misleading. At worst, the recommendations could put patients' health at risk. The drug, thymosin alpha-1, has never been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for any condition, nor has it been proven safe or effective for treating COVID-19. The company that supplied Fradin-Read the drug has also faced scrutiny from the federal government for alleged violations of lab safety standards.

An NPR investigation has found that Fradin-Read's practice is one of more than 30 medical practices and compounding pharmacies across more than a dozen states that have made unproven claims about this drug on their websites and on social media. It remains unclear how many Americans may have taken the drug since the pandemic began, though one doctor told NPR that she had prescribed it to more than 100 patients. The cost of the drug can run up to $400 for a month's supply — all out of pocket.

Fradin-Read defended her practice's prescriptions of thymosin alpha-1 and said she believed the drug was safe and effective. Still, after NPR's inquiries, VitaLifeMD's social media posts regarding the drug were removed from Facebook and Twitter. No evidence has emerged that her patients or others across the country have experienced any serious side effects from the drug. A representative of Goop declined to comment on the record about that company's connection with Fradin-Read.

NPR's investigation also revealed how these misleading claims proliferate. Three elements are necessary: first, laboratories — known as compounding pharmacies — manufacture, promote and supply the drug. Next, doctors, such as Fradin-Read and others who market the drug more widely and prescribe it to patients. Finally, the government agencies with responsibility for regulating drugs and misleading advertising fail to deter many offenders amid a flood of coronavirus-related scams.

Where is the drug coming from?

Like a lot of misleading health information, the claims about thymosin alpha-1 have some basis in truth. That can make it even more difficult for patients to figure out whom or what to believe, especially if the information is coming from doctors.

Over the years, thymosin alpha-1 has been studied as a potential treatment for a handful of illnesses, including hepatitis B, certain cancers, and even the 2003 SARS outbreak. Regulators in China and more than 30 other countries have approved the drug for some of those conditions under the brand name Zadaxin. The drug is a synthetic version of a substance naturally produced by the human body and has been shown to stimulate the certain immune responses.

In the U.S., the FDA granted thymosin alpha-1 an "orphan drug designation," which provided incentives to research the drug as a potential treatment for rare conditions. But most drugs that receive that designation never hit the market, and thymosin alpha-1 was no exception.

The FDA has never granted thymosin alpha-1 approval for treating any condition.

Because thymosin alpha-1 is not approved by the FDA, it's unavailable through pharmaceutical companies in the U.S. Instead, it's reaching consumers through an alternative source: compounding pharmacies.

The term "pharmacy" can bring to mind CVS or Walgreens, but compounding pharmacies are often more like small drug manufacturers that mix and sell customized drugs.

The FDA has said they play an important role in the health care system. A compounding pharmacy might make a version of a drug for a patient with an allergy to one of the regular ingredients, for example. But the FDA does not test or evaluate drugs made in those pharmacies. So even though those drugs may be legally prescribed, they are never considered "FDA approved."

For years, experts have warned that drugs made in compounding pharmacies can be dangerous, especially since lax lab standards can heighten the risk of contamination. In the most well-known incident linked to compounding pharmacies, in 2012, mold-tainted drugs from the New England Compounding Center sickened more than 700 people with meningitis, killing 64.

"They are subject to a lower quality standard, and so it's very important that they really only be used when medically necessary," said Julie Dohm, a former FDA official, who led the agency's work on compounding pharmacies.

Some of these pharmacies actively promote drugs that may not be medically necessary.

Wells Pharmacy Network, for example, sells "custom wellness medications" for weight loss and "aesthetic dermatology." In April, the compounding pharmacy also promoted thymosin alpha-1 on Facebook along with the hashtags "#coronavirus" and "#covid."

The FDA has also found problems with the company's practices. In 2014, the FDA alleged the company's "products may be produced in an environment that poses a significant contamination risk," and in 2016, Wells Pharmacy Network issued a nationwide recall for hundreds of products after FDA investigators found "microbial contamination."

Wells Pharmacy Network did not respond to requests for comment.

Tailor Made Compounding, based in Kentucky, made an even more explicit pitch for thymosin alpha-1 as a COVID-19 treatment.

In early March, just as the coronavirus was gaining a foothold in the country, a company leader named Ryan Smith gave an online presentation on the "Best Peptides for COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Prevention." He told a group of health care providers that Tailor Made Compounding had several drugs that they could "sort of market to your patients" during the pandemic.

In his presentation, Smith repeated the falsehood that thymosin alpha-1 is "FDA approved," and he recommended the drug to his audience as a treatment for Lyme disease, "general anti-aging," as well as the coronavirus.

NPR's investigation identified multiple concerns with Tailor Made Compounding and its leadership.

In April, the FDA told the company its inspectors had found "serious deficiencies in your practices for producing sterile drug products, which put patients at risk." After a 2018 inspection, the FDA highlighted a "sterility failure" with a batch of thymosin alpha-1. The agency also found that the company did not perform "identity testing" on the raw materials they use to make drugs — raising questions about whether those drugs are accurately labeled.

Smith, who has identified himself as the company's vice president of business development, has also been the subject of criminal investigation. In 2015, he was arrested for allegedly placing a hidden camera in the women's bathroom at the University of Kentucky and taking photos without people's consent, according to widespread news reports. Court records indicate he was convicted of "voyeurism," and a Kentucky State Police database lists him as a registered sex offender. The records note that his victim was 16 years old.

Smith and Tailor Made Compounding CEO Jeremy Delk did not respond to multiple phone and email messages seeking comment.

It's unclear whether the people watching Smith's presentation were aware of the FDA warnings or criminal charges.

What is clear is that Smith's pitch for thymosin alpha-1 reached doctors around the country, several of whom cited the presentation in their own promotions. During the pandemic, Smith said, "If [patients] can only afford one product, this would be the one for both prophylaxis and treatment."

From compounding pharmacies to doctors and patients

Fradin-Read in Los Angeles was one of the doctors that the message reached. She obtained doses of thymosin alpha-1 from Tailor Made Compounding, according to her Instagram Live video, and called the company "one of the best pharmacies."

NPR found medical practices widely marketing thymosin alpha-1 for COVID-19 based in Michigan, Tennessee, Texas, Florida, Iowa, New York and California, among other places.

Not every practice discloses how much it charges for these injections online, but a handful of companies list prices in the range of $369 for a one-month supply, or $400 for a "ten-syringe set."

Most of the medical practices that promoted the drug are not specialized in infectious diseases but rather focus on plastic surgery or promote "wellness," "anti-aging" and "regenerative" medicine.

Experts say the claims about thymosin alpha-1 show how some doctors can misuse patients' trust to help create a market for drugs that haven't been proven to work. "Sometimes it's the primary care physician or doctors in general who are major sources of misinformation," said Leigh Turner, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota Center for Bioethics.

After NPR contacted Fradin-Read to discuss her prescriptions of the drug, she acknowledged that it was inaccurate to describe thymosin alpha-1 as "FDA approved." Nonetheless, she said, "I use thymosin alpha myself and have even given it to people who have serious issues, even my mom when she was fighting cancer."

Fradin-Read also said "thymosin alpha has tons of studies" in scientific literature supporting its use for infectious diseases. For example, she sent NPR a link to a small, nonrandomized study from China, where the drug is approved. That study found some benefit in reducing deaths in severe cases of COVID-19 and was published in the scientific journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

The editor-in-chief of that journal, Dr. Robert Schooley, told NPR, "These early studies do not imply an endorsement of the agent in question, and should not be cited as that by those selling the drug without FDA approval." Other researchers shared Schooley's concerns. Cynthia Tuthill is a former chief scientific officer at SciClone, the pharmaceutical company that sells the brand-name version of the drug abroad. When Tuthill learned American doctors were marketing the drug as a purportedly "FDA-approved" COVID-19 treatment, she said she was "horrified."

The Federal Trade Commission and the FDA have also taken issue with such claims. The agencies warned three companies that promoting thymosin alpha-1 as a coronavirus treatment is "unlawful" because such claims are "not supported by competent and reliable scientific evidence," and demanded they remove those claims within 48 hours.

Another medical practice promoted thymosin alpha-1 on Facebook and its website and featured a YouTube video, falsely claiming the drug was "approved by the FDA." Lindgren Functional Medicine obtained thymosin alpha-1 from both Tailor Made Compounding and Wells Pharmacy Network according to its owner, Dr. Kristen Lindgren.

In an interview with NPR, Lindgren said she began prescribing thymosin alpha-1 early on in the pandemic "to give people something that they can do [so] that they felt like they weren't helpless." And because she viewed the drug as so safe, she said, that "it was better than doing nothing, in my opinion."

Past FDA warnings against the compounding pharmacies didn't concern Lindgren because "the pharmacies that we use have been thoroughly vetted," and she trusted the companies' reassurances. She said she had prescribed the drug to more than 100 patients and had not seen any adverse reactions.

When NPR brought up the fact that thymosin alpha-1 has never received FDA approval, she said, "I'm sure you know how I feel generally about the FDA." Asked for what she meant by that comment, Lindgren replied, "I'm gonna take the Fifth on that."

Lindgren rejected the idea that her claims about thymosin alpha-1 might have been misleading. She pointed out that her video and website stated the drug had not yet been studied as a treatment for COVID-19 and that she characterized the drug as one way to support the immune system.

After her interview with NPR, Lindgren's webpage about thymosin alpha-1 appeared to be removed, and the YouTube video was set to private.

When asked whether she was concerned about possible enforcement from the FTC or FDA, she replied, "honestly, no."

Who's enforcing the law?

Experts said misleading claims about drugs like thymosin alpha-1 proliferate not just because there's a motive to make a profit, but also because the consequences for breaking the law are often low. The vast majority of online posts marketing thymosin alpha-1 as a COVID-19 treatment have remained up for months.

The two agencies leading efforts to crack down on misleading health claims are the FDA and FTC.

"Given the limited resources of both the FDA and the FTC, they've done about the best they can," said Bonnie Patten, executive director of the nonprofit watchdog Truth in Advertising. "But it's definitely not enough to stop the multitude of scams and schemes that are out there."

The FDA did not answer questions for this story, stating only, "There are no FDA-approved drugs to prevent, treat or mitigate COVID-19."

The FTC has issued more than 300 warning letters related to a wide array of alleged coronavirus scams, three of which dealt with thymosin alpha-1.

In a statement, Rich Cleland, assistant director for the FTC's Division of Advertising Practices, said, "The scope and magnitude of the FTC's efforts to stop the marketing of fraudulent COVID-19 treatments is unprecedented."

Patten said out that warning letters, though a "slap on the wrist," are often effective — especially if a company mistakenly broke the law. But she said they do little to deter companies that intentionally flout the rules. The FTC can also take companies and individuals to court. But given its limited resources, the agency typically only takes action against the most egregious violations.

Turner said the lack of enforcement action can sometimes provide a kind of tacit approval of potentially illegal behavior.

"It doesn't just allow these businesses to continue to operate and make unsubstantiated marketing claims," Turner said. "I think it's also a kind of a green light to the marketplace."

Turner, Patten and other experts are advocating for additional resources for the FTC and FDA to enforce existing laws and to use lawsuits or even criminal investigations to stop companies from misleading consumers.

Otherwise, Patten said, for some companies, "false marketing pays and it's worth the risk."

Have you been prescribed thymosin alpha-1? We'd like to hear from you. You can reach Tom Dreisbach attdreisbach@npr.org

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))