Note: NPR's First Listen audio comes down after the album is released. However, you can still listen with the Spotify and Apple Music playlists at the bottom of the page.

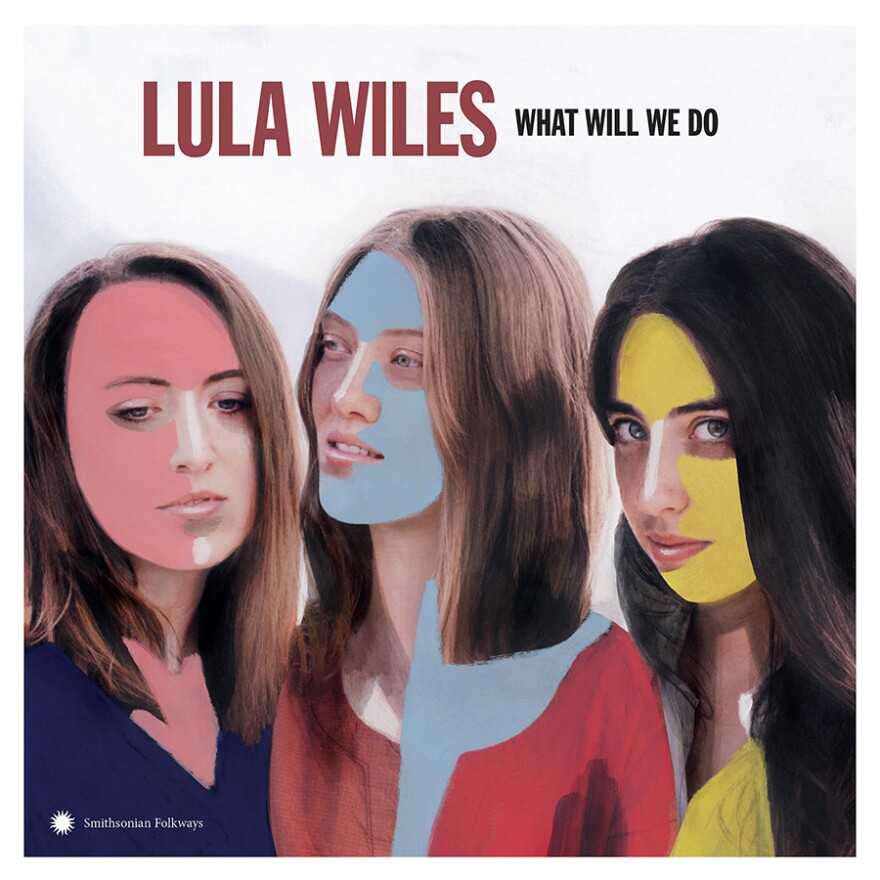

Across the roots, country and bluegrass landscape, it's a banner moment for bands of visionary, virtuosic women, from Pistol Annies and Runaway June to I'm With Her, Sister Sadie, Our Native Daughters and Della Mae. Their spirit of solidarity and collaboration feels timely; at a moment when the verisimilitude of women's accounts is receiving special scrutiny, they're making room for each other, displaying their pleasure and belief in the talent, voices and perspectives of their colleagues. Lula Wiles — a band consisting of Isa Burke, Eleanor Buckland and Mali Obomsawin, who share in common their backgrounds in both fiddle camps and the elite conservatory setting of Berklee College of Music — is newer to the national stage, but developing rapidly.

The trio's second album, What Will We Do, displays a mastery of traditional styles and idioms, as heard in the cutting closeness of their country harmonizing in "The Pain of Loving You," learned from Trio's version, and the forlorn, old-timey fiddle melody that courses through "Leave Me Now." But Obomsawin, Buckland and Burke also apply energy and intelligence to confronting and reimagining tradition. The pointedness of the liner notes they wrote for this dozen-song set underscores their connection to the folk lineage of protest music, though they offer an important corrective to its tendency to bypass questions of representation; they insist that folk music catch up with social discourse and reckon with who gets to speak for whom. At the same time, they're also working with a template laid out by Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, whose subtlety and composure opened a space for delicate, postmodern sophistication in the way that acoustic performers engage with antique-sounding narratives and forms (as evidenced by the refined interplay of Lula Wiles' picking and singing during "If I Don't Go" and "Love Gone Wrong"). The trio belongs equally to the new generation of singer-songwriters who lean into personalized particularity and mine the complexity of their inner lives.

It's Buckland, Burke and Obomsawin's skill at shifting and sharpening vantage points and fine-tuning tone and inflection that holds all these threads together. They transform an earthy Irish ballad, inspired by Mary Delaney's rawboned a cappella performance, into an atmospheric meditation on women's effortful agency, their voices drifting in and out of crystalline three-part harmony. "Bad Guy," their take on a murder ballad, comes from the perspective of an avenging sister, its violence dramatized by Burke scraping her fiddle bow across the strings. Their downhome string-band romp "Nashville Man" drolly depicts the embarrassment of a woman who awaits signs of affection from an indifferent long-distance lover; Obomsawin's twang-less, cannily unemotional delivery lands far closer to indie-rock than to the demonstrative expression we usually associate with country singing. The results are equally compelling when Lula Wiles adopts a more contemporary, confessional approach. "If I Don't Go" evokes a swelling sense of claustrophobia, as its protagonist pivots from being quietly horrified at the possibility that she's contorting herself into a shape her significant other will find more desirable to fantasizing about escaping to an untethered, self-determined existence.

The three bandmates make distinctive contributions to some of our most contested areas of social and political discourse. Lula Wiles' tributes to small-town life — the painfully pretty "Morphine" and the evocatively detailed "Hometown," both of which reflect realities to which they've borne witness — don't fall into the familiar postures of idealizing rural ways of life or blindly blaming the people desperately trying to hang on in those places. The exaggerated, luxuriant ease of Obomsawin's vocal phrasing during the waltz-time number "Good Old American Values" skewers and satirizes American pop culture's celebration of Native people's subjugation. Obamsawin, who is Abenaki, lays out her intentions in the liner notes: "As an Indigenous songwriter, I hope that it becomes equally unacceptable to write and sing anti-Native lyrics as it now is to write and sing anti-Black lyrics. Unfortunately, Indian hating is a good old American tradition. In fact, American culture has depended on it. ...The best I can offer is to reclaim and repurpose the rhetorical and aesthetic space of country music carved out for me by colonialism, in pursuit of beauty and truth."

The Appalachian melody of "Shaking As It Turns" has an austere yet life-and-death urgency, and the frailing banjo figure, antsy drum cadence and slippery, insistent upright bass part combine in a propulsive pulse. In the song's lyrics, Lula Wiles decries superficial soothing of our social strife as troublingly insufficient. "So don't talk about love if your love won't burn," Burke pleads softly, "if your love won't fight, if your love won't yearn, 'cause a love don't win if it waits on some return." Delivered so artfully, their concerns are hard to shake off.

Stream the Album

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.