In flood-ravaged Colorado, much of the recovery has focused on rebuilding roads and bridges to mountain towns cut off by last month's floods. But take a drive east to the state's rolling plains, and a whole new set of staggering problems unfolds in farm country.

LivingInLimbo

A woman named Claudia, who doesn't want to use her last name because of her immigration status, is sitting on a couch in the lobby of a shabby hotel in Greeley, about an hour's drive northeast of Denver.

She's come because a friend has been staying here. Both women lost their homes when the floodwaters wiped out the mobile home park in the nearby town of Evans.

"Where can we go?" Claudia says in Spanish. "We lost everything in the floods — all of our clothes, everything, from our 10 years living here."

Her husband is trying to keep his construction job. The family has been told that they qualify for FEMA assistance because her youngest daughter was born in the U.S. and is a citizen. But the agency is still processing their application, and she doesn't know if it's been approved.

The rental market here was already tight due to an oil boom. The women say landlords are preying on them, asking them questions like: "Have you received FEMA money? How much did you receive? What is your immigration status?" And the county hasn't returned her calls for help finding an apartment.

These are common stories being told right now across this flooded region, where thousands of immigrants from Mexico and El Salvador have flocked to jobs in the fields and the dairy and meatpacking industries.

"Many of these families that were displaced and taken out of their homes, and currently are homeless, are the workforce of northern Colorado," says Sonia Marquez of the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition.

By the coalition's counts, hundreds of immigrant families have lost their homes. Some don't have any family members who are citizens and eligible for aid. Many are turning to private charities like hers, Marquez says. And some churches are trying to raise money to buy families new mobile homes.

But money is tight. Almost everywhere you look around hard-hit towns like Evans, there's a need.

A Town Overwhelmed

The floods hit this town of about 19,000 people hard. The east side, where most of the immigrant community lives, took the brunt of the storms.

In one neighborhood along the South Platte River, which swelled its banks when several levies broke five weeks ago, half of the road is gone. Mud and trash is strewn everywhere. Feral cats are mingling around a van where an elderly couple has been living for a month.

The town's main wastewater treatment plant is still offline. Auxiliary pumps are being used to hook it onto Greeley's larger system that wasn't destroyed.

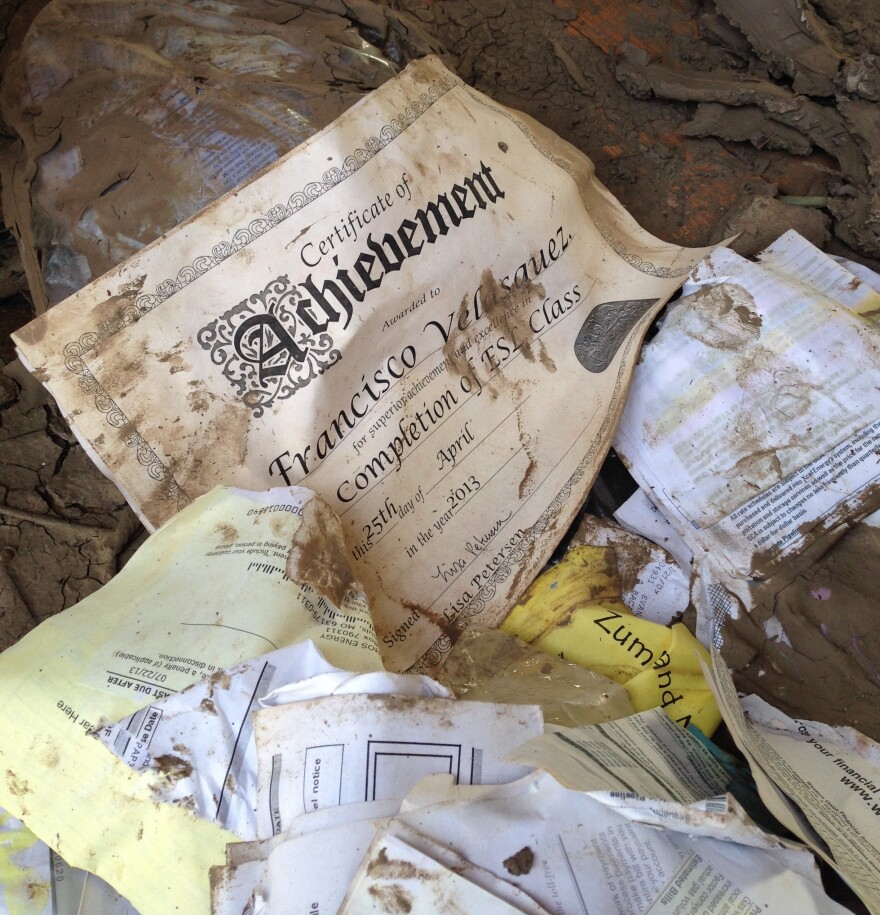

At one of the decimated mobile home parks nearest the failed plant, Lyle Achziger, the mayor of Evans, points out what's left of a girl's English as a second language certificate. A layer of raw sewage and mud and chemicals covers what used to be the family's living room.

"Who knows what was in that water," Achziger says. "It was all coming across here — 8, 9 feet high in here."

A FearOfComing Forward

As of the 2010 Census, Evans was about 45 percent Latino, but Achziger says immigration status did not affect who got help. The focus was to find residents shelter and food, to see that they were taken care of.

"We don't bring that up, whether they're documented or not," he says. "We had people that were living in here and they were in a desperate situation. Some of these people barely got out of here with their lives."

In the days after the worst of the flooding, the town of Evans had bilingual staff on hand at shelters and meetings to answer questions and point people toward help. Today, FEMA seems to be doing the same.

But some people are afraid to ask for help because of fears of deportation. FEMA says that fear is unfounded.

"Our first and foremost mission is to make sure that each individual has a safe, healthy environment in which to continue their journey," says William Lindsey, the agency's northern Colorado spokesman.

Back at the hotel, there's some good news for Claudia's journey. A man in a navy blue FEMA jacket has just walked into the lobby. He's a native Spanish speaker, and he's helping her check on the status of her application.

No word yet. But she says she's determined to make it through one way or another. This is home, she says.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))