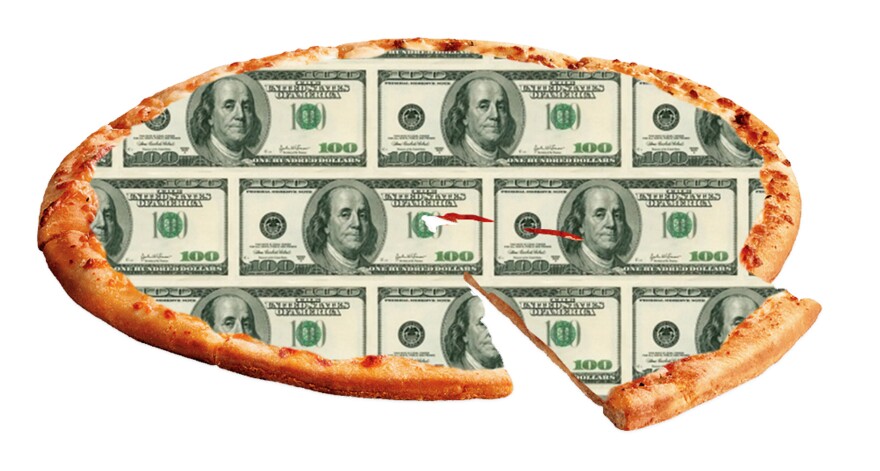

We all know that American college education isn't cheap. But it turns out that it's even less cheap if you look at the numbers more closely.

That's what the Wisconsin HOPE Lab did. The lab, part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, conducted four studies to figure out the true price of college.

To get a sense of student realities, researchers interviewed students on college campuses across the state of Wisconsin. But they also examined 6,604 colleges nationally and compared their costs with regional cost-of-living data from the government.

The researchers found that college life is more expensive than sticker prices might suggest, and that financial aid doesn't help students as effectively as it could, especially after the first year. All these findings are summarized in a report from The Century Foundation.

Colleges want to keep their sticker price low because it helps with rankings and attracts more students, the report says. But students might be less likely to drop out or take time off of college if they could better plan their college finances.

Here are some key findings:

College cost-of-living estimates are too low.

Schools can survey students to figure out how much they're spending, and use that as their cost-of-living number.

But the money students report spending might be lower than what they should be spending. The students interviewed were scrimping on basic needs — everything from food to health and dental care.

Students living at home aren't always saving money.

More that 70 percent of stay-at-home students studied were helping their families pay bills. But because those students lived at home, they got less access to aid.

Some majors are more expensive than others.

Students in nursing had to pay for lab work and vaccines. Other majors required expensive study-abroad experience. And some STEM majors found that their textbooks were too expensive and dropped out, or switched majors.

Even students in majors like English faced hidden fees. Some paid hundreds of dollars to take an online course when required classes were overbooked.

Low-income options are often the least cost-effective.

Take meal plans. The plans with the lowest price gave students the least bang for their buck.

If students could afford a laptop, they got free software and other perks. But students who had to rent out laptops were hit with steep fines if they failed to return them in the short borrowing period. If they couldn't afford to live on campus, it was more difficult to return equipment on time.

Financial aid calculators overestimate how much parents can pay.

The calculators don't take into account parents' debt, for example, so they may ask for a larger contribution than the parents can actually afford.

The price that the student pays can increase each academic year.

Forty percent of students studied saw an increase in their share of the bill going into their sophomore year — the median was $1,215. The number jumped again between the second and third year.

Many grants focus on freshman year, and drop off afterward. Students can also lose grants if they don't know that they need to refile for , or don't understand that they need to meet academic requirements to keep their grant.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))