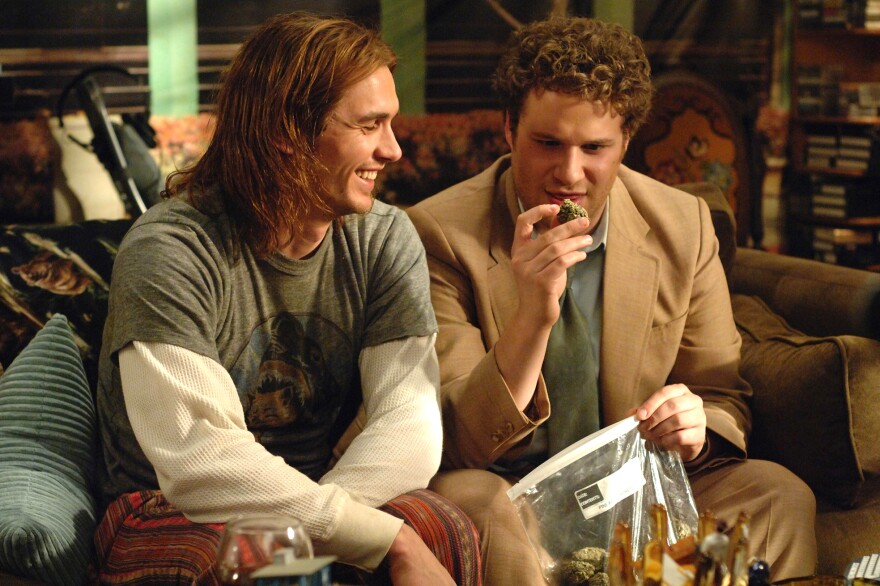

Shortly after toking up, a lot of marijuana users find that there's one burning question on their minds: "Why am I so hungry?" Researchers have been probing different parts of the brain looking for the root cause of the marijuana munchies for years. Now, a team of neuroscientists report that they have stumbled onto a major clue buried in a cluster of neurons they thought was responsible for making you feel full.

This cluster, called the POMC neurons, is in the hypothalamus, a region of the brain that scientists typically associate with base instincts like sexual arousal, alertness and feeding. Tamas Horvath, a neuroscientist at the Yale School of Medicine and the team's leader, says that the POMC neurons normally work by sending out a chemical signal telling the brain, you're sated, stop eating.

In the past, when neuroscientists shut down POMC neurons in mice, all the mice became morbidly obese. Horvath figured that in order for the drug in marijuana — compounds called cannabinoids — to spawn that undeniable impulse to feed, it would have to bind the activity of these neurons and make them fire less. Paradoxically, Horvath says, "We found the exact opposite."

The team discovered that when they injected cannabinoids into mice, the drug was turning off adjacent cells that normally command the POMC neurons to slow down. As a result, the POMC neurons' activity leapt up. At the same time, the cannabinoids activate a receptor inside the POMC neuron that causes the cell to switch from making a chemical signal telling the brain you're full to making endorphins, a neurotransmitter that's known to increase appetite.

These two effects combined create a kind of runaway hungry effect. "Even if you just had dinner and you smoke the pot, all of a sudden these neurons that told you to stop eating become the drivers of hunger," Horvath says. It's a bit like slamming down on the brakes and finding weed has turned it into another gas pedal.

Jessica Barson and Sarah Leibowitz, two neuroscientists at the Rockefeller University in New York City, say that the study is pretty innovative. The idea that a neuron would flip from firing off one chemical signal to giving the complete opposite signal in this way is a new one, and Leibowitz says that reveals an important driver of overeating in general. And Barson says Horvath's team has just done some excellent experiments. "It's really beautiful to read a study like this," she says.

One caveat is that the study — which appears online in the journal Nature — was done on mouse brains, not human ones. But Horvath says the hypothalamus is such an ancient part of the brain, something that evolved before mammals, that he'd "bet his life" the way these neural circuits work in mice is the same in humans. Barson says that until you do the experiment with humans, "you can't know for sure, but it's reasonable to conclude that it's the same thing."

The study is not, however, the final missing piece of the munchies mystery. A lot of other neural processes get layered on top of what goes inside the hypothalamus, and cannabinoids affect those other parts of the brain as well. Last year, researchers found that cannabinoids lit up the brain's olfactory center, making mice more sensitive to smells. Before that, other researchers discovered cannabinoids were increasing levels of dopamine in the brain; that's the swoon that comes with eating tasty things.

Horvath says the neural circuitry that cannabinoids are subverting in the hypothalamus is the fundamental driver for hunger. It has to do with basic survival. But he also agrees that the munchies are probably the sum result of cannabinoids acting all over the brain.

"For anyone who's experienced it — you realize that's exactly what's happening," he chuckles. "You just can't stop, no matter how much you put in your mouth."

Angus Chen is a journalist and radio producer based in New York City. He's on Twitter: @angrchen

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))