A self-driving car hurtles toward an individual and their dog. The car’s brake-lines are cut and the machine must decide — kill the person or the pet. What would you do? What if the dog were yours and the person were a stranger?

Western Carolina University professor Hal Herzog uses personal anecdotes and philosophy to think about pets on his blog “Animals and Us” for Psychology Today. He highlights scientific publications and asks readers tough questions like, “If my cat is family, should I imprison it indoors?” and “Is a cloned dog less natural than a purebred?”

Herzog joins guest host Anita Rao to explore what pets reveal about our paradoxical views on animals. Hal Herzog is the author of “Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It’s So Hard To Think Straight about Animals.”

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS:

On loving a killer cat:

The more we think of animals as people — that is to say, the more we think of them as creatures with a degree of autonomy — the more morally problematic are our relationships with them.

So for example, with my cat Tilly, I like to give her some autonomy, including the autonomy to go outside. And she exhibits this autonomy by killing small, lovely little creatures. So I'm faced with this moral dilemma. You know, should I make Tilly live inside the big cage called my house where she stares out and frustratingly looks at the world floating by all day? Or should I let her go out and be her true cat killer self?

If you actually look at the impact that cats have on wildlife, it's really quite significant. Somewhere between one and five billion birds are killed each year by our love for cats. This [dilemma] is really exemplified by my friends that are vegetarians or vegans. They don't eat meat almost always for moral reasons. Yet many of them live with cats, and their cats don't share their moral concerns about eating meat — cats are obligate carnivores. And so they have this fundamental moral dilemma about loving an animal that happens to be a killer.

On The Pet Paradox:

I'm increasingly starting to wonder about the ethics of pet ownership, the more we recognize the idea that animals are creatures that have a sense of themselves. We say that we consider pets as family members, but we don't really treat them as family members.

For example, we would not cut the reproductive organs out of our human family member. We would not make a human family member eat the same dreary dried food every day for the rest of his life. We would not let a human family member never go outside or rarely go outside without being tied to a leash. We would not intentionally breed human family members for deformities, which is what we do with some dogs.

On perceiving animals as natural versus unnatural:

We actually did a study of what people consider natural in animals. This isn't based in reality, it's based in what people perceive animals to be. So we developed a little scale to compare, for example, the naturalness of a wolf compared to the naturalness of a purebred dog, compared to the naturalness of a clone dog. And what we found out was that people perceived a purebred dog as being about 70% as natural as a wolf. On the other end, they perceived a clone dog as being about 30% natural as a wolf. So cloning makes a dog —in terms of the way we evaluated mentally — way less natural.

On valuing pet lives over humans:

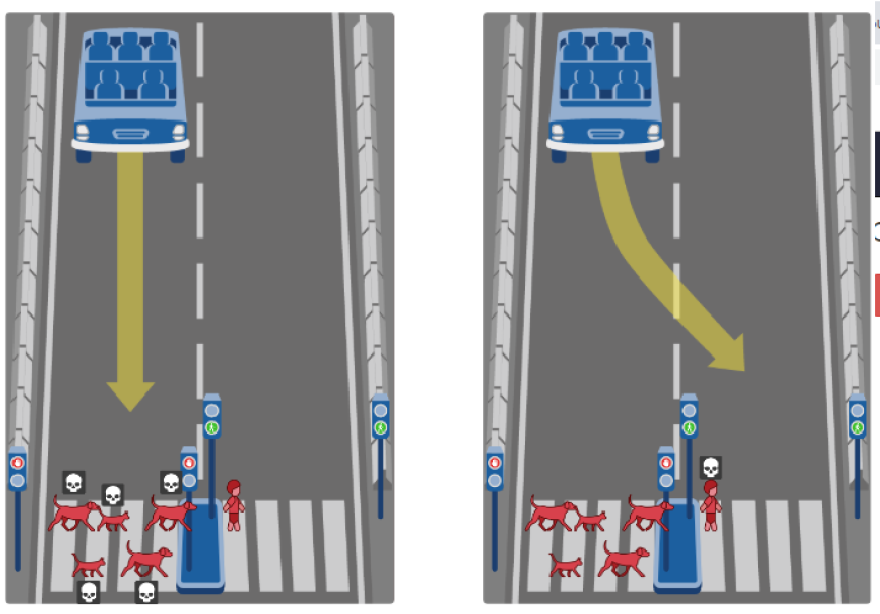

Let me explain the trolley problem first. The simplified form is this: There's a trolley going down a set of tracks. There's three people standing on the tracks ... There's a lever that you could pull that would make the trolley go to another set of tracks where there's one person. The question is: Should you pull the lever? A utilitarian person kills one person as opposed to three people. And most people say, yes.

So, for example, at a crosswalk, they have animals crossing the tracks. What we find out is that worldwide, people overwhelmingly choose to sacrifice the animal to spare the person.

A group of researchers at Georgia Regents University made a very slight change … and you could save one creature — it would either be a person or a dog. When it came to saving a foreign stranger versus a dog, the vast majority of people said that they would save the foreign stranger over a dog.

Then they ask another group of people: Well, what if it was your dog? In that case, it changed quite a lot. In this case, 40% of people said that they would save their dog, even if it meant the life of a foreign stranger. By the way, one of the most interesting differences was a sex difference. Women were much more likely to save the animal than they were the person.

On the potential for robot pets:

Sony is sending me a robotic dog to play with for a couple of weeks. The robotic dog's name is Aibo and it’s supposed to arrive tomorrow. Sony originally developed this robotic dog about ten years ago. And it's expensive. It costs about three thousand bucks. But it’s computer controlled, and apparently is pretty amazing. It's so amazing that studies have shown you can take Aibo into, for example, a nursing home and let people play with it. And they found that it was equally as effective as playing with a therapy dog.

So I'm excited about that. I do have moral concerns about bringing real animals into our lives, especially the way that we're doing it. To me, I'm hoping I'm going to fall in love with [Aibo]. But I think it’s not going to happen.