Saturday marks one year since the discovery of a massive gasoline spill on the Colonial Pipeline in Huntersville, north of Charlotte. Officials say they're still researching the extent of the spill and they aren't sure how long it will take to clean up. As one of the largest gasoline spills on land in the United States, it continues to raise concerns from neighbors and officials from Huntersville to Raleigh to Washington, D.C.

Owen Fehr and Walker Sell were riding a two-seat all-terrain vehicle along the Colonial Pipeline right-of-way last Aug. 14 when they smelled gasoline.

"It was just an overwhelming smell," Sell said. "And then you almost couldn't breathe, but we just kept going because Owen thought it was normal for some reason, because we were on a gas line. And then as we came back through that same spot to leave, we could see it coming out of the ground."

Fehr said the grass was dead and gasoline was still spilling from the pipeline several feet underground.

"It was all brown, and then it was kind of like puddly," Fehr said. "And the gasoline that was coming out of the ground was just kind of slowly bubbling out."

Back at Fehr's house a half-mile away, the boys, now both 16-year-old juniors at Hough High School in Cornelius, decided to call 911. Firefighters arrived within 10 minutes, Fehr said.

"They thought we were kind of joking with them that there was a gas leak back there," Fehr said. "And they didn't really think that it was that big of a deal. And then next thing you know, there's 10 fire trucks there. Hazmat … everybody was there."

It turns out Fehr and Sell had stumbled across what authorities now say was a spill of historic proportions.

"The 1.2 million gallon(s) — the current estimate of the release, which is no longer accurate — is a significant release and the largest in North Carolina history," said Michael Scott, who oversees the state Department of Environmental Quality's waste management division. "And it has the potential and is already in the realm of being one of the largest on-land fuel releases in the country."

Colonial initially estimated the spill at about 60,000 gallons, but that proved to be way off. In January, it raised that to about 1.2 million gallons. As of this week, Colonial has recovered 1.225 million gallons of gasoline. And there's still more in the ground.

Colonial has not offered any new estimates or a timeline for the cleanup. Workers are still recovering about 1,000 gallons a day, down from a high of 5,000 gallons.

The Colonial Pipeline is nearly 60 years old, running 5,500 miles from Texas to New Jersey. It's actually two pipelines, a 36-inch pipe for diesel, jet fuel and other fuels, and the 40-inch gasoline pipeline. Spills are not unusual. One in Alabama in 2016 brought a two-week shutdown that caused gas shortages on the East Coast. Two months later, an explosion shut it again.

But this was bigger. It happened in the Oehler Nature Preserve about a mile east of downtown Huntersville, a couple hundred feet from the closest road. It's a section of pipe that's 42 years old and Colonial says it came at a crack in a previous repair — called a "Type A Sleeve." Officials still aren't exactly sure how long gasoline was leaking.

"It was, we believe, days or weeks," Colonial spokesperson Meg Blackwood said during a tour of the site Tuesday.

That's days or weeks that gasoline was pooling around the underground pipeline, seeping up to the surface and down into soil, rocks and groundwater.

"So when we responded to the incident, there was product above the ground, and we safely responded to it," Blackwood said. "First responders were called in. Our people immediately mobilized and went into our emergency response procedures, which are designed to protect human health and the environment. Those are always our priorities."

A section of the pipeline was shut down for five days. As with other spills, Colonial dispatched an army of employees and contractors to the site — as many as 250 at a time. They've spent more than 180,000 work hours so far.

About 8,700 tons of soil were removed and taken to the Speedway Landfill in Concord. Contaminated water is still being collected from wells, stored in tanks, then shipped to a recovery facility in Asheboro. Meanwhile, powerful vacuums suck up gas vapors from the soil. Then they're piped to what's called a "flame oxidizer," where they're burned off.

At one point, the pipeline was dug up and exposed while workers repaired the leaking section. Today, it's closed up again with fresh fill. And Colonial is working with Mecklenburg County Park & Recreation to replant the site with native vegetation. But even as a few Brown-eyed Susans bloom, it belies the contamination that remains.

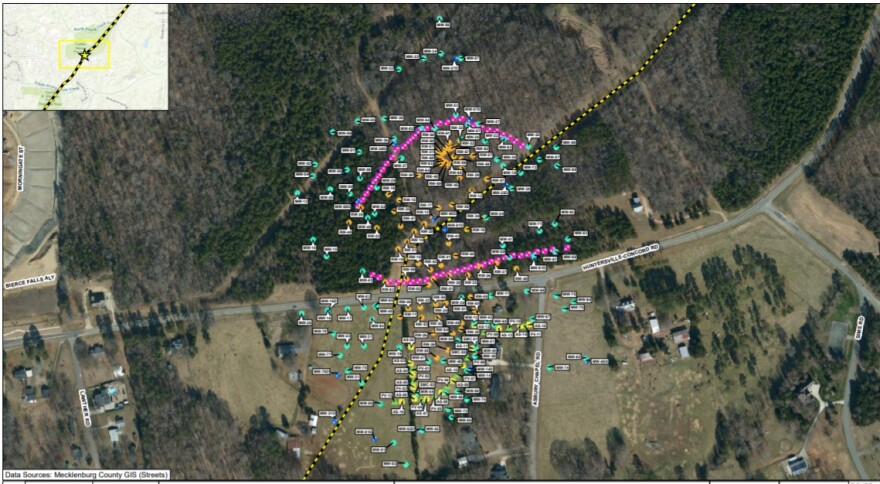

Colonial has dug 281 wells to date — some to gauge the extent of the seepage and some to pump gasoline from the soil. Those wells have mapped about a 12-acre area in the 142-acre nature preserve where contamination has been found.

A year after the incident, state regulators are requiring Colonial to add more deep wells, said Scott.

"How deep this contamination goes to bedrock or what that underlying surface looks like, we're still yet to define," he said.

Colonial's inability to answer questions has brought criticism from state environmental officials. In April, when the company said it needed more time to update a key report, then-DEQ Secretary Dionne Delli-Gatti refused. In a statement she said: “It is unacceptable that for eight months Colonial Pipeline has been unable to provide a reliable accounting of the amount of gasoline released into this community. We will take all necessary steps and exercise all available authority to hold Colonial Pipeline accountable for what has become one of the largest gasoline spills in the country.”

So far, the work has cost Colonial about $30 million. That includes paying to connect four homes to public water lines and to buy three houses near the spill. Some workers are living in the houses now, and the fields behind them are a staging site for heavy equipment.

The spill and lack of information has brought frustration and lots of questions from neighbors, town officials and state and federal regulators. Jake Cohen lives in Pavilion Estates just north of the spill and talked with WFAE shortly after the spill was discovered.

"We all have wells. Every single house in this neighborhood has well water," Cohen said. "So, to not know whether or not your well is going to be affected short-, medium- or long-term, is scary."

Since then, Colonial hired an outside firm to test private well water near the site and says so far no contamination has been detected.

Still, Huntersville Mayor John Aneralla said the spill's size and continued uncertainty is "unnerving."

"I've learned that they don't have internal systems that are strong enough to detect over a million-plus gallons leaking," he said.

Blackwood said Colonial does regular inspections using what's called a "pig," a device that runs inside the pipeline. She didn't say why this leak went undetected.

"We have a really robust system-integrity program that predates the Huntersville incident," Blackwood said. "But of course, we continuously apply learning from the incident."

Huntersville officials want more information. Aneralla said he's frustrated that the company has not given the town board a formal update in months. Huntersville Commissioner Stacy Phillips agreed.

"I hate it, I hate everything about it," Phillips said. "And the fact that we are nowhere close to this being over and done with is really concerning."

Just how long all this equipment will be here seems to be anybody's guess. State regulators' records show smaller gas leaks on the Colonial Pipeline have case files that remain open for a decade or more.

Spokesperson Blackwood said: "What I want the community of Huntersville to know is we're dedicated to being here as long as it takes to remediating the site and cleaning up the environment. We understand the impact it's had on their lives. And we certainly didn't want this to happen, but we are committed as we have been since Day 1 to stay here until the job is done."

It's not clear whether state or federal regulators will hit Colonial with penalties. An agreement with federal pipeline regulators in July requires the company to improve its leak detection system and maintenance. But the deal rules out further administrative proceedings or lawsuits and came without immediate penalties. The DEQ's Michael Scott said North Carolina hasn't decided on final regulatory actions or fines because it still doesn't know the extent of the spill.

State Sen. Natasha Marcus of Davidson, who represents the area, has introduced legislation to study pipeline safety in the state. It's stuck in committee. She agrees that there are many unanswered questions.

"We still don't have an updated estimate of how many gallons are down there, whether it's traveled, how much damage it might have done," Marcus said. "And, of course, we don't know the answers to the big questions, which is how did this happen? And how did they not know that it was leaking? How long was it leaking? We deserve to know those answers."

Meanwhile, there's also the big picture about pipelines. Climate activists who protested in Huntersville last month criticized the environmental damage. But they also have broader concerns. Hannah Stephens of Charlotte is with the youth-led Sunrise Movement.

"This localized disaster is a microcosm of our larger national dependence on fossil fuel companies," Stephens said. "Not only does it lead to devastations like this, but it also is a leading contributor to the climate crisis."

Stephens says her organization wants to see the U.S. stop building pipelines altogether.

Copyright 2021 WFAE. To see more, visit WFAE. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))