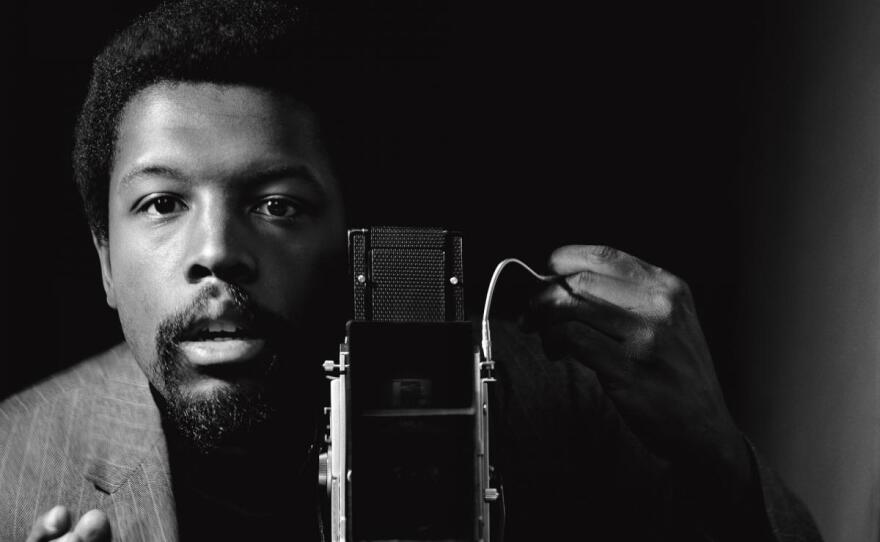

The iconic photography that championed the “Black is Beautiful” movement is currently on display at the Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem. Eighty-four-year-old photographer, arts community organizer and activist Kwame Brathwaite chronicled the second-wave Renaissance of his beloved Harlem, New York. He also promoted Black leaders like Marcus Garvey and challenged white beauty standards of the day.

Reynolda Fellow and professional photographer Owens Daniels tells WFDD’s David Ford that “Black is Beautiful” represents all aspects of Brathwaite’s work and the exhibit leaves him feeling reflective.

“What’s beautiful about me — inside of me?” asks Daniels. “Outside of my character and my soul, I’m wrapped in this beautiful Black skin. Not only Black is beautiful, but being a human being is beautiful. And he’s able to capture a human being wrapped in this Black skin and they have just as much value as the rest of the cultures in this world.”

Interview Highlights

On Brathwaite’s jazz musician photography:

He himself was a musician, but he was also a part of the community. You’ve got to remember a lot of times jazz clubs were very small. The owners lived in those communities. A lot of the jazz musicians, when they play from downtown, they will come back up to Harlem at night and have these long [jam] sessions. So, him and his young friends, they would sneak into bars, they will sneak into clubs, and they will get to meet these musicians.

On Brathwaite's activism:

He was an activist; he was very interested in Black revolution. They called it a Black nationalism. It all came from Marcus Garvey, the idea that you see here [written] on the wall, ‘Think Black. Buy Black.’ And that ideal is the idea that you have self-worth and you can create your own economic power in your own communities.

On Grandassa Models:

And here was the idea that Black is beautiful, which is a very revolutionary idea within itself. The Grandassa Models came in, and that concept came in to highlight the beauty of the aesthetics of the body of the Black woman, the skin of the Black woman, the hair, the clothing and bring back this ideal. We're gonna bring this beauty not from Tokyo, not from New York, not from Paris. We're gonna bring it from Africa. Grassland or Granddassa for us is the African continent itself, representing the Black woman. Everything we need comes from that. This is when you walk into Grandassa, and this is when you walk into the style, and then you walk into the grandeur of these beautiful Black women where you have these four portraits on the wall.

On Brathwaite’s portrait of his wife Sikolo Brathwaite:

The erectness of her, the dignity and class, her hair, her clothing, her gaze, all those things give me the sense of Madonna. But when I look at this picture, I'm not turned away that she's not looking at me — that she's not looking toward me. In fact, that gaze gives her more class and dignity and her stature in the way that she's posed. It gives that sense of Madonna from the ideal of beauty.

*EDITOR'S NOTE: This transcript was lightly edited for clarity.