Lawmakers recently passed a bill reducing the size of the North Carolina Court of Appeals. Republicans said the court's caseload is down, but Democrats complained the only motivation was to prevent Governor Cooper from making appointments.

So who’s right?

The caseload for the North Carolina Court of Appeals has decreased in recent years. However, that doesn't necessarily mean the workload has been reduced as well. It doesn't mean it hasn't gone down either. It just means there are fewer cases. And any single case can take much more judicial effort than another.

Consider that a three-judge panel of judges would spend far longer considering the constitutionality of a brand new law than it would an appeal of a speeding ticket. This is an extreme example, of course, but it illustrates the point. A simple reckoning of cases doesn’t tell the full story.

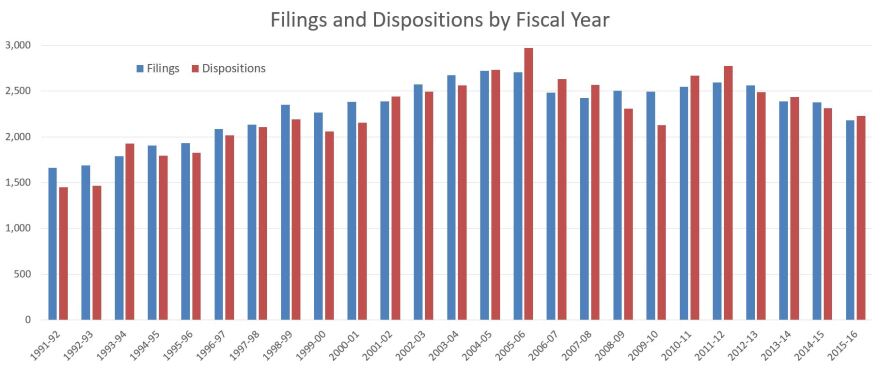

From the late 1970s through 2000, the N.C. Court of Appeals consisted of 12 judges, but the caseload increased during the 1990s. In the early part of that decade, the court disposed of an average of 1,660 cases per fiscal year, or 147 per judge. That increased to 2,040 per fiscal year in the second half of the decade, or 180 per judge, on average.

With the additional caseload, the N.C. General Assembly increased the court from 12 to 15 members.

At the beginning of 2017, the court's makeup consisted of 11 Republicans and four Democrats. However, because of a mandatory retirement age, three Republican judges would reach retirement before the end of Governor Roy Cooper’s term. If Cooper were to appoint three Democrats to fill those seats, it would have swung the party breakdown to 8-7 in favor of Republicans.

Enter the 2017 General Assembly, which passed House Bill 239 to reduce the size of the court from 15 back to 12 as the next three judges retire. Cooper vetoed the bill, but the General Assembly overrode the veto.

In a wrinkle, Judge Doug McCullough, a Republican, retired 36 days early. His retirement came in time for Cooper to appoint a new judge, Democrat John Arrowood, to his seat. This could cause logistical problems if future judges retire and are not immediately replaced because the Court of Appeals operates in three-judge panels.

HB 239 sponsor and advocate Representative Justin Burr did not respond to multiple phone messages. But supporters of the bill argued that the Appellate Court's workload had reduced back to pre-2000 levels, and cutting its size would save taxpayer money. Appellate Court judges in North Carolina receive a $133,000 salary, according to The National Center for State Courts, based in Williamsburg, Virginia. That figure ranks North Carolina 41 among the states for that position, according to the group.

The court's caseload has been on a downward trend since 2011-12, which raises the question of why the General Assembly would choose this year for a quick move to reduce its size. Furthermore, Bill Raftery, a senior analyst with The National Center for State Courts, said that doesn't necessarily mean less work.

In order to truly determine how much an Appellate Court judge has worked, the center literally sits with a timer and observes the time devoted to the motions, petitions and appeals each judge receives. Then extrapolates into a full year to estimate actual time spent considering cases. Raftery said the center hasn't done a study like this for North Carolina and if one were to happen, it would take many months.

"Weighted caseload studies take longer than a single legislative session," he said. "Caseload is not the same as workload."

While comparing the caseload of North Carolina judges to those from other states might seem to make sense, Raftery said there is no good way to take an "apples to apples" look.

Appellate Courts operate much differently from state to state. Jeff Welty is a UNC-Chapel Hill associate professor of Public Law and Government and director of North Carolina Judicial College. He compared caseloads of North Carolina judges against those of Virginia, Tennessee and Georgia. In Virginia and Georgia, judges saw caseloads well above those in North Carolina, while judges in Tennessee handled significantly fewer.

Welty acknowledges the "differences in accounting conventions and case mixes," and that these should not be considered "apples to apples" comparisons.