Video by Jacob Karabatsos

Audio by Aurora Charlow

Jolene Sliwka was searching through a thrift store for vintage t-shirts and used records 35 years ago when she picked up a “scratch-off-and-sniff” Valentine’s Day card and added it to her haul.

That little card set off a scavenger hunt that has now become a collection of several thousand vintage valentines, Sliwka has preserved on her Vintage Valentine Museum Facebook page. When she started, she had no idea that some of the cards she bought for a few dollars would sell for over $1000 or that there are hundreds, if not thousands, of other collectors who are on their own heartfelt hunt.

“The world is cruel; these little things are pretty,” Sliwka says.

Every weekend, Sliwka, her husband, and her collection can be found at Granddaddy’s Antique Mall in Burlington, N.C. Inside the warehouse, a scene that resembles a farmer’s market unfolds. But instead of fruits and vegetables, vendors sell and package the produce of the past.

Sliwka has always been a collector. Her house in Burlington is sheltered by thousands of records lining the walls and decorated with valentines, 365 days of the year. On her site, she posts her collection for her fellow collectors and historians. Some of her most special cards are framed, hanging like posters or are tucked away like private love tokens for her and her husband to enjoy.

The cliche ideas of Valentine’s Day – the roses, chocolates, and construction paper cards – are not what this collection is about. The history of Valentine’s cards is rich: they are the love letters of culture’s past.

Sliwka’s personal obsession led her to connection with others who share her same passion. The National Valentine Collectors Association is a community with over 900 active members. The president, Nancy Rosin, is a collector of ephemera, specifically valentines and devotionals. Their Facebook group is a platform where members exchange ideas about valentines and post photos of their cards.

To Rosin, vintage valentines capture modern hearts because of their universal message of the desire to feel loved and their ability to display history.

“There is really nothing that was sacred that wasn’t captured in valentines,” Rosin said.

You’ve heard the old woman

who lived in a shoe,

Had so many children she

didn’t know what to do

Till good old St. Valentine asked for a few

So they could be bringing my

greetings to you!

The origins of Valentine’s Day are unclear. Tales of St. Valentine matchmaking soldiers and their wives in 200 A.D. or attempting to convert Roman Emperor Claudius to Christianity all end with his death as a Christian martyr. Some scholars believe that the Roman Feast of Lupercalia – a fertility festival from the 3rd century BCE – birthed the holiday.

The tradition of giving valentines started in the 1800s with better access to the printing press and quality paper, according to Associate Professor Elizabeth Nelson from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

In Massachusetts in 1847, Esther Howland’s father handed her a valentine from a business associate of his. While looking at its craft, Howland had a thought: I can do better than this.

Her father purchased supplies for her to begin creating valentines, and she convinced her brother to take them on a sale’s trip to sell them. Within a year, she had over 5,000 orders to fulfill, starting a business out of her parents’ home.

Howland, now referred to as the mother of American valentines, propelled a revolution in the industry, says our expert Rosin. She combined craftsmanship with an assembly line of women, hand making and standardizing her craft. Before selling her business in 1879, she was making over $100,000 a year,

“She’s the innovator of factory methods. Long before Ford was doing that,” Sliwka said.

Today, Howland’s valentines are some of the most expensive and coveted among collectors. The earliest vintage valentines Sliwka owns are Howland’s creations.

“One of the crazy things about this is, for a lot of us, the valentines we remember are the school ones that we exchange. And these are pretty inexpensive ones. Penny valentines. But some of these ones, the big Esther Howland’s, would cost $50 back in 1870,” Sliwka said.

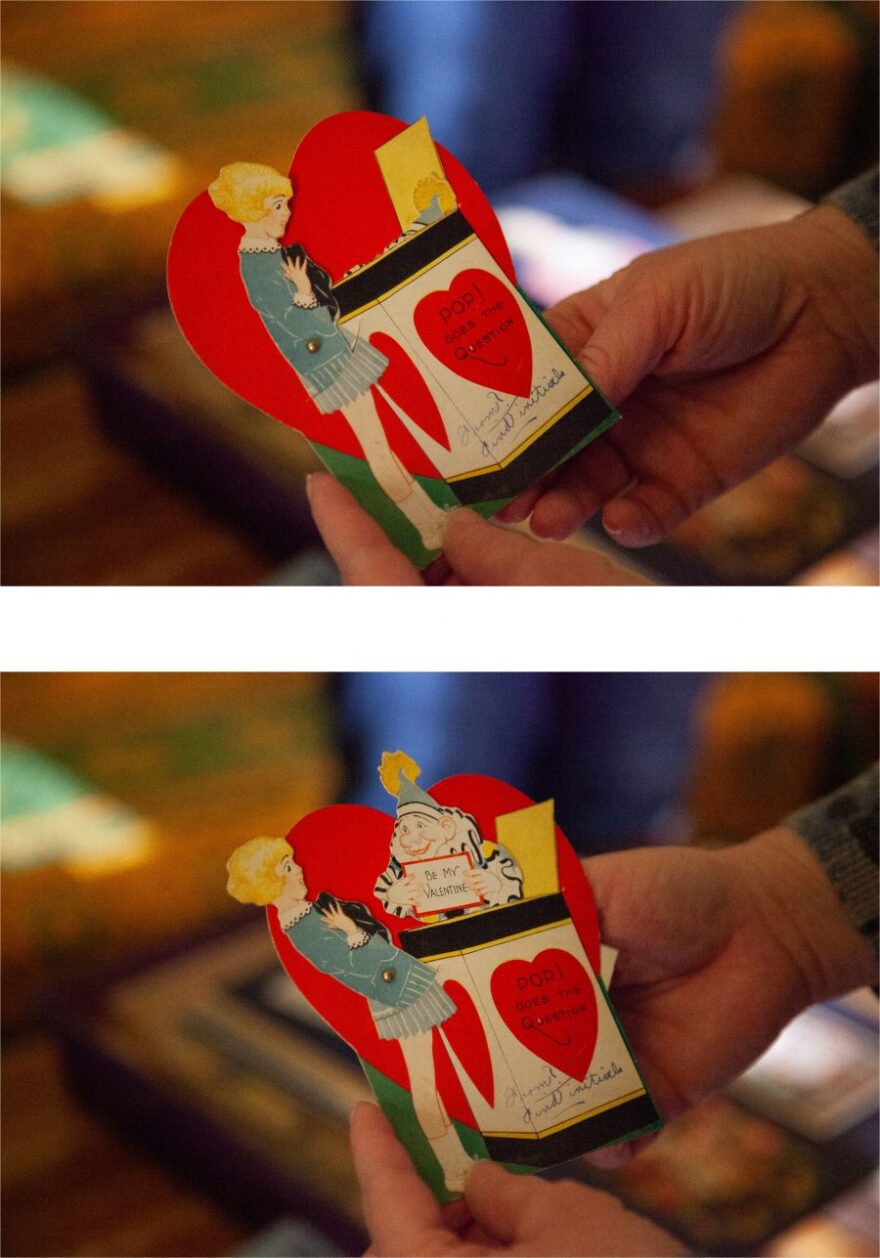

Pop! Goes the Question.

Be My Valentine?

On her museum website, Sliwka champions the work of female artists from the 1900s like Francis Brundage, Chloe Preston, and Ellen Clapsaddle. Her favorite style comes from Chloe’s work in the 1920s. She points to a 3D valentine illustrating a burning house as an example of the attention to detail the artists employed.

While her love for the art and romance is fierce, she acknowledges the darker sides of the tradition as well.

Several years ago, an infamous valentine surfaced on Ebay, sparking a conversation about what collectors call Vinegar Valentines. This particular card showed a lynching: an example of a period in the 1900s, when some Valentines became increasingly cartoonish and often cruel.

Blackface and racist portrayals were part of the mainstream valentine market in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, says Sliwaka.

Vinegar Valentines grant unique access into personal lives of those who came before while creating the collective picture of the culture in which they lived.

“If we lose or ignore our history – good things, heroes, warts, all of it – you don’t really know exactly where you are or even who you are. And that’s why, I would say, it’s important,” Sliwka says.

To my Valentine,

Whether Valentine’s Day

is rosy or blue

Depends entirely My Dear,

on you.

The market for vintage valentines is niche, but the buying and selling of them can be profitable for the collectors and those with whom they connect.

When Rosin spent several thousand dollars on valentines from England in the 1800s, her gut told her she needed to do something special with them. Whimsical scenes of knights with large feathers jousting for a woman’s love and the delicate shapes of ferns danced on the cards. Their cutouts earned these valentines the name “papercuts.”

In tribute to the love letters that survived nearly two hundred years, Rosin published a piece in the Ephemera Society of America’s Journal featuring the papercuts and mentioning the author, Elizabeth Cobbold, by name.

A few weeks later, she received a call from an unsaved number.

“My name is Anthony Cobbold. My friend in Boston recently read your article in the Ephemera Society of America’s Journal and recognized my last name. I am Elizabeth’s great-great-great grandson. I live in England. You found her valentines. I had to speak with you.”

Rosin eventually went to London, visiting the home of Elizabeth Cobbold and meeting her great-great-great grands.

That set of valentines from hundreds of years ago created a lifelong relationship across oceans. Thousands of miles away, in Burlington, valentines by artist Francis Brundage featured on the Vintage Valentine Museum spark controversy about racism. The thousands of collectors who preserve vintage Valentines are all caretakers of history, says Sliwka – and the cards provide a window into the collective public life of those who came before.

“Humans, we’re a mixed bag. We’re sometimes really awful. “ Sliwaka said. “But we’re also sometimes really lovely people who make Valentines.”

I Thought That in the Theft Dear, You’d Never Take Part,

But I Have to Arrest You for Stealing My Heart.