With Toscanini, you got such a sharp, delineating beat, you knew exactly what he was looking for. He would go after the key points he wanted, get it cleared up, and then he would conduct from beginning to end. He would work very intensively, and when he got what he was looking for, he would say, 'Basta, go home.'

A little more than 60 years ago, conductor Arturo Toscanini gave his first televised concert, leading the NBC Symphony Orchestra. April 4 will mark the 52nd anniversary of his last public performance. It brings to mind the maze Toscanini left behind.

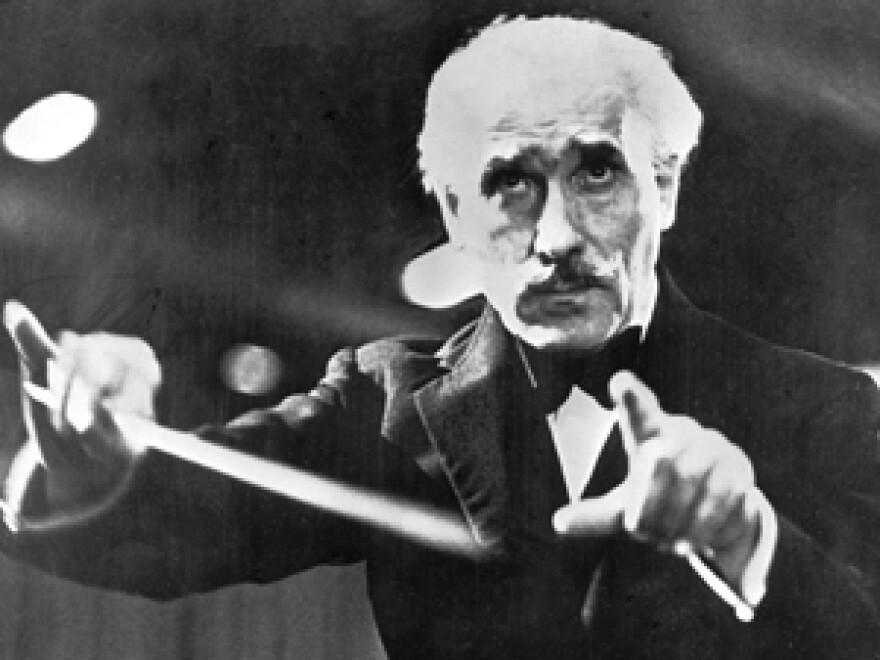

It starts and ends with music, of course, but in between, there's this man stamping his feet and waving his arms to get his way. There are powerful disagreements about his musical gift — as well as decades of musical tradition and remarkable history.

Perhaps the most internationally famous conductor ever, Toscanini rose to instant stardom when he put down his cello and jumped up to the podium to fill in for the conductor during a performance of Verdi's opera Aida. It was 1886; he was 19, and it was the first time he'd ever conducted.

The last time he'd conduct a live performance was in 1954, 68 years later. By then, he was the first conductor to have appeared regularly on television, and was certainly considered the first true media star of the conducting world.

So just by nature of having covered so much ground, Toscanini is of major interest. And now we have books, recordings, DVDs of his broadcasts, exhibitions with annotated scores and photos. All which help us consider the question: What did he actually do?

The Players

Some answers came from the NBC Symphony musicians who worked under him. For one thing, he rehearsed like crazy. "When you play in an orchestra, there's always a little push and pull," bassist David Walter said in a 1992 interview. "If you get a very good conductor, you get close to what he is thinking, but never exactly. And that's the thing that haunted Toscanini. For him, that was a frustration that lasted all through the years."

To get exactly what he wanted from 100 players at the same time, Toscanini is said to have done everything a human could do: yell, sing, dance. In his heyday, the press loved to write about his histrionics, his physical and mental excesses. It wasn't all invention.

"He was extremely sensitive in every way," said violist Harold Coletta, also interviewed in 1992. "Very harsh, at many times, and very, very cruel with his insults. He was like a child who couldn't control whatever he felt. It was spontaneity and sometimes very ugly spontaneity with his insults."

For all his vocal and physical demonstrations, it was said that Toscanini was also very business-like. "With Toscanini, you got such a sharp, delineating beat, you knew exactly what he was looking for," Walter said. "He would go after the key points he wanted, get it cleared up, and then he would conduct from beginning to end. He would work very intensively, and when he got what he was looking for, he would say, 'Basta, go home.'"

He was also blessed with a phenomenal memory, especially when he was conducting opera. "He knew all the lyrics, all the words," Coletta said. "And he would sing them in his falsetto — sometimes a little out of tune, or like a whiskey tenor. But he knew every word."

All About The Music

So with all that, did Toscanini make great music? Well, there's debate about that. Joseph Horowitz's book Understanding Toscanini, published 20 years ago, insists that making great music was not what he was about. He says Toscanini and the media of the period reduced music to a kind of middle-of-the-road masterpiece mentality that's been seriously harmful. On the other hand, Harvey Sachs, a biographer of Toscanini, sees him as deserving of our admiration for his great contribution to music. Toscanini brought conducting into the modern age, say his supporters.

Continuing through the maze, I begin to listen to some famous Toscanini recordings. The famous Dvorak "New World" Symphony recording of 1953 is one people talk about, and it has an excitement that's undeniable. I can hear the strong rhythmic element for which he was famous.

Listening to it, you can see how Americans might have learned to love the famously anti-fascist Toscanini, a self-made conductor who left Europe in the '30s and settled in at NBC in New York. With an orchestra made just for him — and a custom-built studio, too — he plowed his way through the classics.

Later, when he turned up in the early days of TV, it was practically the first time anyone, other than the musicians in front of him, had seen a conductor's face at work. "The television cameras brought them around to the other side," says Walfredo Toscanini, the conductor's grandson. "That was a revelation, and that will last forever."

No conductor ever received the kind of adulation Toscanini did in his days traveling around the country. Life magazine said he was as famous as Joe DiMaggio. "It was an adventure, and the youngest person, the one with the most energy, was my grandfather, and he was 83 or 84 years old," Walfredo Toscanini says.

It's hard to imagine now an era when a conductor could mean so much — when a classical concert could be a major cultural event. That's where I come out of the maze. I can't get too involved in criticizing or picking apart the performances. There's too much other information here about the music and the culture of the era.

To watch and to listen is to see how one person, stamping his foot and waving his arms, captured the undivided attention of 100 players — and a whole world of listeners. For me, that's plenty.

Note: This essay was first broadcast in 2007.

Copyright 2008 WNYC Radio