The artist and thinker, who just released a new album that's only one part of a larger multimedia conception, takes us from the drummers of Burundi to Adam Ant, Octavia Butler to David Bowie, Rakim to Young Thug. We also hit on ageism in rap, artistry for sale and how to work interviews.

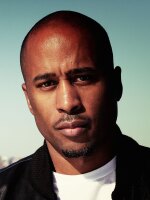

ALI SHAHEED MUHAMMAD: Saul Williams in the house! What up?

FRANNIE KELLEY: Thank you for coming.

SAUL WILLIAMS: Chilling, man. Very excited. New album out, MartyrLoserKing. Project I've been working on for a long time. It's multimedia, so music is one of the branches, but it's the first branch to reach the public.

MUHAMMAD: OK.

WILLIAMS: So, super excited about this conceptual piece, and, you know, its introduction to the public forum.

MUHAMMAD: How long have you been working on it?

WILLIAMS: About two-and-a-half, three years. In several capacities.

I started working — I work through music first, like even before I approach words. Even if I'm writing poems, like, I'm either responding to music or through music or I'm enjoying the musicality of an idea. In this sense, I started with sounds, and that's what you hear in the first track "Groundwork," is the beginning of me playing with sounds, trying to envision this parallel universe.

It's a concept album, and it tells the story of a hacker named MartyrLoserKing. And he lives in Burundi in Central Africa, and it's about the sort of like hacking stunts that he does that makes him a virtual phenomenon before he gets labelled as a terrorist.

MUHAMMAD: Right.

WILLIAMS: So I pulled all of that story out of the music, first. And then the first people I approached — simultaneously when I started shopping the demos to the label that I wanted to help me put it out, I started shopping the text to graphic novel companies. And so I ended up landing both deals.

MUHAMMAD: Wow.

WILLIAMS: And so I'm finishing the graphic novel now and have released the first half of the music.

KELLEY: Oh, OK.

WILLIAMS: That's what this album is. There's another album coming that will come out around the time of the release of the graphic novel, which will be about a year from now.

MUHAMMAD: So you say that the — you do the music first and that's — you draw the inspiration from the sound.

WILLIAMS: Yes.

MUHAMMAD: Carving out the sound. It's a — bit of it sounds somewhat futuristic and somewhat, like, retro, but retro when retro — when, I guess, an older form of electronic music was being progressive.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: How — I'm just trying to understand how --

WILLIAMS: How do I play with that --

MUHAMMAD: Yeah, how do you play with the — yeah.

WILLIAMS: — with those both — connecting those dots? Well, yeah --

MUHAMMAD: Yes. Thank you for helping with that.

WILLIAMS: Nah. I mean, on one hand, I'm — you know, the future — the big misconception about the future is that the future is now.

MUHAMMAD: Yes.

WILLIAMS: We're always living in the future. Right now. Right? And so we can project ideas about what that sounds or looks like. And you hear those things, from Close Encounters — "doo, doo, doo" — and all those ideas and what have you.

But the fact is that many of the ideas that we're playing with have existed for eons. Like if you look at — if you look closely at — go to a museum and look at Egyptian sculpture and hieroglyphs and what have you. The precision in that work — I don't mean what we commonly see. Like if you really go and look at that work that's 4,000, 6,000 years old, you'd be like, "How the hell did they do this without machines?"

MUHAMMAD: Right.

WILLIAMS: "How is that possible?" They're drawing images that look like cartoons that are on the Cartoon Network right now. And the only thing you can say is, "OK. Maybe they had less distraction, and so they could apply more energy to the idea." Right? And I get the same thing musically when I listen to — what I am using sometimes in MartyrLoserKing is field recordings.

MUHAMMAD: OK.

WILLIAMS: Like so on the — there's a song called "The Noise Came From Here" where I use a sample from Rwanda of a group called the Twa. And the Twa are the forest people, you know, often referred to as peasants or what have you, but it's the forest people. And there's a forest song that they're singing, which we might call a work song or a field song, or what have you. But the polyrhythm is everything that we have in the idea of digital, in the idea of funk.

MUHAMMAD: Wow.

WILLIAMS: What they're playing with, it's old, but if you tried to do that now, it would sound like the most modern thing ever.

It's the same thing with like — in the story of MartyrLoserKing, there is a character named Po Tolo, and Po Tolo is actually a Dogon word. The Dogon are from Mali, and they were stargazers. They actually plotted the constellation of Sirius B --

MUHAMMAD: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: — hundreds of years before NASA.

In fact, the first 50 years of NASA, which is what we're up on right now, were pretty much them just confirming the stuff that the Dogon had plotted for centuries, and going, "Yup. they're right about that too. Yup. They're right about that too. I don't know how they saw it with the naked eye. But they're right about that too."

And the Dogon believe that — they say in their cosmology, they say that they are from Sirius. And their numerological system is binary — 01010101 — which has everything to do with coding.

MUHAMMAD: Right.

WILLIAMS: Right? And so that's what I'm — that's why I base the story on the continent of Africa, because we have these antiquated ideas, we have these pitiful ideas, we have these romantic ideas, surrounding the continent. But the thing we don't talk about is that, one, it's the continent where the largest number of people are connected to the Internet. Two, it's the continent — the only continent — where the majority of the public is under the age of 25. Now add those two things together. It's the future, right? And that future is now.

And if you look at the sort of innovations that's going on there — like there's a guy in Ghana who just made a 3-D printing machine out of found objects.

MUHAMMAD: What do you mean out of found objects?

WILLIAMS: Meaning out of old parts that had been thrown away.

In fact, the story of MartyrLoserKing takes place in a area that we call MartyrLoserKingdom, and it's right next to an e-waste camp. And so this is what I mean by found objects. One of the phenomenons of the continent — and other places as well — is that, of course, 80% of coltan or cobalt — the precious stone that is in our smart phones and laptops, distributes power — 80% of that is found in the Congo and the Great Lakes region of Central Africa. That's where our story takes place.

And so those ships that take out the coltan are the same ships that bring in waste, e-waste. And by e-waste I mean that, of course, we replace our monitors, our computers, not when they're dead, oftentimes, but when the new thing comes out. So where do those things go? They take those things to places where scavenger culture exists, so that they can — where people will take the time to take out the copper and take out anything that's recyclable.

And so my character MartyrLoserKing actually is wandering and arrives at a place where it's miles — it's like the size of a city, but it's just piles of motherboards, monitors, and all this. But he needs shelter, and so the first part of the story is him building a house of old computer parts; other people follow suit, and so you end up with a village made of old computer parts.

MUHAMMAD: Did you spend — how much time did you spend in Africa?

WILLIAMS: In Africa? My first time in Africa was in 1994.

MUHAMMAD: OK.

WILLIAMS: My mother was an exchange teacher. I graduated from college, and my graduation gift was to spend her final month there with her. And so she was in the Gambia, and so we went to the Gambia, Senegal and Mali. That was my first trip. I was there for like a month-and-a-half.

Pretty bizarre trip, partially because there was a coup d'état in the Gambia while we were there, and so the borders were closed. And I had a great experience, which was we had to listen to the radio to find out what we were supposed to do, cause there were all these kids running around with machine guns in the street. And they said all Americans should find safe haven at the home of the American ambassador. They gave the address.

So my mom is there with a delegation of African-American teachers; there were nine of them, and me. It was all women and me. And so we go to the house of the American ambassador, a person from the CIA. I say that because they had that thing in their ear, you know? It was a guy — the suit and the thing in the ear like, "May I help you?" Of course, he said "May I help you?" cause we're in the Gambia. And so we were African-American. We looked like other citizens there until we open our mouths.

And so we're like, "Yeah, we're American. We heard on the radio that this is where we're supposed to come to find food and shelter." And the guy goes, "Oh, if I had known you guys were coming I'd have pulled the grits out the pantry." Yeah.And then I — it was the first I ever heard my mom curse somebody out.

But, you know, that was my first trip. I got to encounter — there was a lot of things. I started writing poetry on that trip. Because, primarily, the thing that got me, as a New Yorker, was, without the intrusion of lights, the sky is amazing. The number of stars, the proximity of the moon, all the stuff I had never paid attention to. So suddenly I'm paying attention to that, and that's pretty much when I start writing.

The food, the music, the conversation, all these things were amazing. The only negative experience I had — I mean, there were things — like at that time, I remember listening to Illmaticon a train from Dakar, Senegal to Bamako, Mali. It was 37-hour ride. And I remember being up all night listening to Illmatic looking out the window.

And sometimes I'd make the mistake of standing next to other Americans who would see people holding stuff on their head, and living, you know, in like a handmade hut or something, and be like, "Oh, look at the poverty!" Which means that they were looking through the filter of their own experience, labelling something poverty where actually the people were self-sufficient. They were making own clothes, growing their own food.

Poverty is a construct in many ways. Because it's applied to the idea of having and have not, but we're forced to think that we should have certain things. Like, "Oh, if you can't afford an iPhone, if you don't have this, then —"

MUHAMMAD: So is that something — I feel like that's some of the message that's in the new album, because you kind of like touch on it.

WILLIAMS: Very much so. I'm touching on all of that.

I mean, all I really wanted to do with this album is take all of the stuff I'm thinking about, all the stuff that's in the news, all the stuff that people share on social media, all the interesting finds, and kind of dump it in my drum machine and create a thinly-veiled fiction where I can talk about all the stuff that is of interest to me.

KELLEY: And it sounds — it sounds remarkably like an Octavia Butler book or Invisible Man. Like it all --

WILLIAMS: Thank you very much. That's a hugecompliment. The Octavia Butler side. I mean, it's true that the idea of Afrofuturism and all that fits very well with MartyrLoserKing. There is another character in the story named Neptune Frost, who is low-key the hero of the story, and she is a modem, actually.

KELLEY: Oh, I didn't get that.

WILLIAMS: She is a modem. And — yeah, you won't get the story really from the album. Although the song "Think Like They Book Say," for example, is the story of the meeting of MartyrLoserKing and Neptune Frost. You get, like, traces of — the whole story is there in the album but only in ways that I could really pick it out.

KELLEY: OK.

WILLIAMS: The graphic novel will have the full story, and the film that we're developing right now, of course, will have the full story as well. The music is just a taste of that world.

MUHAMMAD: Right. What was the motivation to bring it, the project, from the multiple facets? From the music, from the book — and are you talking theatrical or with your live performance doing something a little special with this?

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: What was the inspiration for that?

WILLIAMS: For me it was about streamlining all the stuff that are of interest to me in terms of my own creative process. For years, I've released an album here, a book of poetry there, done a movie over there, and they're all separate projects. For once, I wanted to have the album, the book, the film, the play all under the same heading: MartyrLoserKing. So just streamlining the experience of what I'm bringing to the table.

MUHAMMAD: It's wonderful.

KELLEY: Makes sense to me.

MUHAMMAD: I feel like in terms of in the past five years of just living, or receiving or consuming music and art, in such a frivolous way, I think it's enriching to have someone really give you an art that's really filling and complete.

WILLIAMS: That's the goal.

MUHAMMAD: Beyond just one piece, one part. And I don't know if many people are thinking that far or that big with it.

WILLIAMS: It's the goal. I think it's easy for us to get down on popular culture and where things are and say, "Wow. People don't listen to albums anymore. People don't buy music anymore. People make playlists of just this song and this song and blah blah blah blah." But I think it's really fair to say that things go in cycles, the way that Bobby Brown — you know?

MUHAMMAD: I knew you were going to go there.

WILLIAMS: You knew I was going to --

MUHAMMAD: Thank you.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. I should tell you the story of the first time I heard that album.

But anyway, things go in cycles. It's really true. And so like when Ja Rule, for example, was on top, you would've never — you'd find it hard to imagine the time period when he would not be on top. The same thing for 50. The same thing for so many people. It's hard to imagine that things go in cycle, that this thing that may be of interest to us right now will not always be of interest to us.

And for example, let's say, the reality show phenomenon.

MUHAMMAD: Right.

WILLIAMS: Which I think is like a down point in the American aesthetic in terms of taste and all that. I feel like it's — we lose something there. But I'm not foolish enough to not realize that Slam was one of the first films where people would walk away and go, "Was that a documentary or fiction?" There's tons of people right now who're like, "I saw that documentary about you. You're from D.C." I'm not from D.C. The film was shot in D.C. You know what I'm saying?

But Marc Levin, when he directed that film in the '90s, was already ahead of the curve and saying, "This is where we're going," and blending reality with fiction in a way so that it's seamless. And it led up to this thing where it was like, "I'm actually interested in reality now." And then the thing in reality shows got to a point where it's like, "It's not even real anymore. This thing is scripted, and this isn't what your life is like," and all this stuff.

And so things go in cycles. Our interest peaks and valleys, you know. And so the idea of creating an album that exists as an album, that has that richness, is something for me that's always corresponded with the level of work that I like to put into my work. It's like a painter who choses to spend 10,000 hours on a singular painting. You may look at it; it may be abstract. You're like, "What is that?" But somebody's going to get that and understand the amount of work that went into that.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: But yeah, we're up against things. I'll never forget years ago being on a plane with Hype Williams, and him looking me square in the face and being like, "Yo, hip-hop is fast food. Hip-hop is fast food." And for me, as someone that grew up rhyming and believing in hip-hop not only because of how fresh it was musically but because I saw the social change and everything connected to it, it broke my heart. It broke my heart that someone with that much power and leverage at that point in his career was looking at the art form that way. And I would say that it was reflected through some of the stuff that came out then.

MUHAMMAD: What do you think of the present state of hip-hop?

WILLIAMS: It's a lot of stuff that I love.

MUHAMMAD: Yup.

WILLIAMS: There's always been a lot of stuff that I love. Like, I love Young Thug, for example.

KELLEY: He does too.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, I love Young Thug.

KELLEY: We both do.

WILLIAMS: I mean, when I hear Young Thug and Travis Scott, for example — Travis Scott making beats. Young Thug in terms of melody and how he's approaching phrasing and what have you, like — what's that thing? "That's my best friend. That's my best friend." There's something beautiful there.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: I'd take that if that was like Enrique Iglesias or some s***. There's something there that's rich, even if the actual content doesn't match the quality of the presentation.

KELLEY: Yet.

WILLIAMS: Yet. It's only a matter of time. It's only a matter of time. It may not be him that does it. I mean, it's a shame that more rappers don't necessarily realize that they could make something better than a quick buck, but that's that fast food thing.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Is that when you're looking for that quick payment s*** — you know, it used to be that Andy Warhol would say his thing about the 15 minutes, but artists would try to defeat that. Really, a lot of contemporary artists are looking for that 15 minutes, no more. They just want 15 minutes, enough to like pop that cherry, cash that check, buy that car. "That's cool. I'm good." Until they realize, "Oh, wait."

But it never aligns you with the people whose names we list when we say the Richard Wrights and the James Baldwins and the Octavia Butlers and the Nina Simones. You know, the people who created on a level. And me, I'm just interested in that level, because that's what always has fed me. And so that's the only way I could pay it back.

KELLEY: So I'm in the middle of writing this piece that's like — I made it a certain distance and now I'm kind of stuck. I think that the phenomenon of rappers using the word artist to describe themselves and writers using that word to describe them is relatively new, and I mean to the exclusion of almost all other terms. It's not just a synonym in, like, a two-paragraph piece.

It's like, people like, "I'm an artist. You can call me a artist." And now I think that it's been around for enough time that it is kind of getting in people's heads, and they're like, "Wait, but I am an artist. And what does that mean now? Does that mean I have dispensation to act crazy? Or does that mean I can make things and not have to explain them, make things and don't think 'em through all the way so they're kind of impenetrable? And you just have to, like, take it."

Or does it mean people feel — have too much social responsibility on them, like I feel has happened to Kendrick. Is that people put too much burden on him. I don't know. Can you help me, please?

WILLIAMS: I think that — I'm glad to see people referring to themselves as artists, and I'm glad we're at a point where you have art rock and art hop and all that stuff, you know. That's cool. Because before that, my pet peeve was around the time when Jay Z was like, "I'm not a artist. I'm a business, man."

And you had a lot of businessmen, the type that I grew up with, that I was finishing homework for, writing rhymes for, and what have you. A lot of drug dealers turned rappers-type s*** who didn't really have the skills of many artists that inspired them to want to do it, but who kind of infiltrated the game for the sake of business.

KELLEY: Right.

WILLIAMS: For the sake of cleaning dirty money, for the sake of making fast money, and the whole nine. And so for a minute, we had a hip-hop that was really run by — I don't mean the industry side run by businessmen — but you had rappers that identified more with being a businessman than being an artist.

KELLEY: OK.

WILLIAMS: And now it's switched. And maybe you can say, "OK. Kanye helped with that. Cudi." There's people that helped with that sort of idea. And I think that's wonderful that kind of switch, that you're talking about.

But what does it mean to be an artist? Well, I think it means something different for everyone else. I mean, the part of me that makes me socially responsible, for example, is not because I'm an artist. It's because I'm alive.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: And because I have a voice. And because I have children. And because I care about people. And that's me. That's me. I could still be an artist and be like, just into my thing. And it wouldn't make my art any more valid or interesting. Someone like me could still be into that person's art without them feeling the social responsibility.

I just don't understand why so many artists don't dabble in that when you can see that the great artists that we put on that list all dabbled in that. That's how they touched that pulse.

MUHAMMAD: Well, some of us as humans, we tend live life on the surface.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: And that's just the way it is, you know.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. Yeah, we do. We do.

MUHAMMAD: Not a lot of introspection. And you float through life, and that's just your purpose. And that's what it is. So --

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: And you leave an imprint, a body of work that --

WILLIAMS: It is what it is.

MUHAMMAD: — finds a way to the masses and influences people, but it's still surface. And there're others who are more than that. So it's just the way it is.

Funny thing. Just talking to my crew last night — we had a group call — and we were just reminiscing on some things and saying that funny --

WILLIAMS: Do you mean thecrew?

KELLEY: I know, right? He just drops hints like that.

MUHAMMAD: Thecrew.

KELLEY: He's ridiculous.

MUHAMMAD: And we were reminiscing and just saying it's funny how when we were like 17, life was just about — and I will say it, cause that's what you think about when you're a young teenager — is just getting some booty and, hopefully, raising your intellect. And you can look — we look back now and go, "OK. Somewhere we took a right turn." A "good turn," I should say.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: And we're blessed to say that. And I think our environment was supportive of that. And some people don't have a supportive environment --

WILLIAMS: Very true.

MUHAMMAD: — that will inspire them to go the depths of their — the potential of creativity and what they could tap into.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, I know --

KELLEY: And maybe the girls you were chasing were demanding more.

MUHAMMAD: Ha ha.

WILLIAMS: For me, I know the girls I were chasing are extremely — I'm trying to say --

MUHAMMAD: I'm just not going to answer that.

WILLIAMS: The girls I chased are what made my content what it is.

KELLEY: See? Thank you.

WILLIAMS: That's why my content is where it is. Those are the most lasting impressions. That's how I learned that long list of names and learned to check that out or check this out or weigh this against that and all that, is because of the type of women I was encountering who were like, "Ah, please. This is what you like? Check this." I can't list the number of times that happened and how many things I wouldn't be hip to if it wasn't for some woman who was like, "Have you heard of this? You know what this is?"

MUHAMMAD: Yeah, absolutely.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: I mean, to answer you, Frannie --

KELLEY: You don't have to.

MUHAMMAD: — the number one in my life, in that regard, is my mom, because she was a record collector.

WILLIAMS: Boom.

KELLEY: Right.

MUHAMMAD: And so she sent me on my way and still does, with so many things with regards to information. So, yeah, a woman's always — rules.

WILLIAMS: Exactly. Yeah. My mom was rushed from a James Brown concert to give birth to me.

KELLEY: Shut up.

MUHAMMAD: Wow.

WILLIAMS: She was literally at a James Brown concert with my two older sisters, and I started kicking. And she had to leave my sisters with a security guard who was a member of my dad's church and get in an ambulance.

KELLEY: Whoa.

MUHAMMAD: Wow.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: So you was getting funky in the womb?

WILLIAMS: There you go.

KELLEY: He is your godfather.

MUHAMMAD: He is your godfather.

WILLIAMS: The real godfather. Yup.

MUHAMMAD: So have you — speaking of a topic of hip-hop, have you done any ghostwriting for people?

WILLIAMS: The only person that I've helped write anything is Kanye.

MUHAMMAD: I knew it! It was just a thought, and I was like, "Nah." And I don't know if that's public knowledge or anything like that, but it was just --

WILLIAMS: It's not really. The only thing I worked on was "Love Lockdown" with him, on 808.

KELLEY: Ah, man.

MUHAMMAD: I knew it.

KELLEY: Ho, man.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: That is the craziest thing.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

KELLEY: That's the best thing.

MUHAMMAD: Especially listening to MartyrLoserKing and I'm like --

WILLIAMS: "This is the album he wants to make."

KELLEY: Wooo!

MUHAMMAD: Well, I didn't think that. But I actually did think — after listening to this album, I was like, "Wow, Kanye really —" I just hear the influence, and it wasn't — I never realized that until listening to your new album. I'm like, "Wow, that's —" I mean, nothing from Kanye cause he's really — I'm a fan of his work.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

MUHAMMAD: But just to see that influence, or hear it, and just wondering had you been approached by other people to do some writing for --

WILLIAMS: Not other people. Kanye is the only that approached me on that level, on many levels. When I was working on Niggy Tardust, he came to a show. And he had ten people on stage at that time. We had four. And he came back and was full of questions like, "How come you have less people on stage than me, and have such a bigger sound? What are you using?"

And so he started flying my MPC guy, CX Kidtronik, out to Hawaii at the time and trying to find stuff out. And then he met with me and Trent to ask about lights, like, "What type of lighting rig are you using? What is this?" And so, yeah, he is someone who's been interested. Aside from that, there have not been other rappers that I have written for, not since I was a teenager in school.

MUHAMMAD: Alright, well, he's a big one, so. But, nah, I just think that the level of writing, the content and the depths are something that a lot of people could benefit from. Not necessarily looking for a shortcut, though, I mean in terms of just looking for a mentor to really usher the level of artistry to a higher state.

WILLIAMS: I know when I first started having money to go to concerts, the first thing I tried to do is try to bring gifts for rappers.

Like I had — I remember someone hooked me up with free tickets to check out The Roots and Common. And I had two copies of — what's his name? Hazrat Inayat Khan, The Mysticism Of Sound. And I had heard something in Black Thought's lyrics and something in Common's lyrics; I was like, "Ah, they're interested in sound vibration and all this type of stuff." I had just finished the book and was like, "This would be interesting for them."

And so the first time I encountered those rappers, I was like, "This is a gift for you." I was that nerdy guy backstage with a book, like, "I have a gift for my favorite artists"-type thing, even though those weren't necessarily my favorite artists, right. Although Black Thought has gone up tremendously.

KELLEY: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, he's — I mean, this is what I want to say, which is unrelated, but I'm here with you, and we mentioned Black Thought. And Tip is another person who makes me think of this. I have the philosophy that rappers, in fact, should age amazingly, that they get more and more graceful, more and more innovative, more and more amazing with time.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: That ageism has no place in hip-hop, that you're — I mean, KRS-One is a good example of that, too.

MUHAMMAD: Yup.

WILLIAMS: You know, who's like, "I can keep up with the best of them, actually. You may tire of listening to me, but --"

MUHAMMAD: I think for a moment in time, that concept was foreign to hip-hop, to embrace that idea or to even embrace artists who have been around for a long time and to think that they have any value. And it's — I think — but right now, that's changing because you can call someone old but so many times, and it's like, "OK. You done trying to hurt my feelings. Can we really --"

WILLIAMS: Yeah. "Can we get into this?"

MUHAMMAD: "Can we get into it? And now I'm laying it out, and now you gotta go back to the drawing board, cause --"

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: And so I feel like — I agree with you completely.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, it's — I mean, if you were to look at the evolution of someone like Monk or someone like Max Roach, it's not like, "Oh, Max is old." I mean, Max was drumming on a level that got better and better, more and more intricate, maybe their — the thing that they're interested in may get more abstract. Or you look at producers, people like Brian Eno or what have you. The stuff — look at — listen to David Bowie's last album.

MUHAMMAD: I have not yet.

WILLIAMS: Yo. I had the weirdest experience that night. The weirdest experience. Which is that I was at my kitchen table, writing, checking on some email stuff, and a friend of mine posted something about the David Bowie album. I'd already listened, and I was like, "Ah, I'm going to listen. I didn't have any music on, but I'ma to turn that on again. I want to check that out."

So I'm listening to the David Bowie album. I listened to it twice, and it's because of this one song that I love, which is called "Girls Love Me." And the chorus is, "Where the f*** did Monday go?" And so I play that one like four times in a row. "Where the f*** did Monday go?" And then I start listening to Diamond Dogs, and while I'm listening to Diamond Dogs, my wife comes downstairs crying like, "Did you hear the news?"

KELLEY: Oh my god.

WILLIAMS: It was crazy. And so then I'm like, "Did you hear this song? Cause it's Sunday night." And it was like, "Where the f*** did Monday go?" Surreal.

MUHAMMAD: Wow.

WILLIAMS: Surreal.

MUHAMMAD: Wow.

WILLIAMS: But, yeah, I think these cats age — I mean, Leonard Cohen. Leonard Cohen I think writes more and more beautiful and simple songs and just saying — just graceful. Like, "Ah, this is all it takes, actually."

MUHAMMAD: Yeah.

KELLEY: Right.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: Hopefully, people will be inspired — and not only inspired but just have the surroundings to do so. Cause, you know, hip-hop is --

WILLIAMS: The support. Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah. There's so much from the infrastructure level that doesn't really support artists to want to continue to create after five years of doing it. Life happens. But I'm interested in that you say that, to know what Rakim would do like in another ten years. Yeah.

WILLIAMS: OK. I love — I mean, the other side of that story — and this is going to — this is the craziest thing for me to say, especially since we're on air. And I just met Rakim, and I love Rakim. I think that it's — I mean, Rakim is very much responsible for the person that I am, you know what I'm saying? Like many of us, like, whoa. It's surreal the level of impact.

There has to be something that is said for the artist who stays on their creative path, that does not swallow the hype or what have you, but keeps on forming challenges for themselves to keep going. And that's funny, because we have no doubt about that in painting, for example.

KELLEY: Right.

WILLIAMS: A painter gets older and older, and they follow their path. And we know — like, "Have you seen what they're doing now?" Sculptors: "Have you seen what they're doing now?" Some filmmakers, not every filmmaker, you know? It really does — some filmmakers get really better and better. Tarkovsky is a great one.

On the other hand, like, I'm hesitant to diss popular names, but there are some established great filmmakers who have films that are out now or have been out recently that don't hold up, because people do other things. They surrender to fear. One of the ways people surrender to fear is, like, rehab. I mean, like, "Get high, n****." No. What I'm trying to say is that — no.

KELLEY: So glad you said that on this show.

WILLIAMS: No, but it's true. It's true that there's some artists that I really wish they kept drinking or whatever the hell they did, because when they started — when they replaced that thing with god and their idea of this submission and all that, their work became a reflection of their fears and weak — nobody's going to say this so I'm going to say it. I'll catch hell for this.

MUHAMMAD: OK.

WILLIAMS: Alright. I'll catch hell for this. That's fine.

KELLEY: OK.

WILLIAMS: But I'm sorry. There are artists who — they reach that point, and instead of like — I mean, basically, I'm saying I don't like quitters.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: They reach that point, and it's a point of fear. I've seen it happen to many artists who become frightened by success — alright — and it's the same way you can get frightened by taking too much of something or whatever. And suddenly you become ultra-religious, right?

And there's nothing wrong with the idea of spirituality, but the idea of religion has to do with this other sort of submission. You submit this thing, and you start aligning the work with, you know, with this other idea. I'm being abstract cause I don't want to diss anybody, but I guess I'll just say that --

MUHAMMAD: You could stay abstract. It's cool.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, yeah. I'm going to --

KELLEY: You always want people to stay abstract.

MUHAMMAD: You know why? Because people have families.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, exactly.

KELLEY: OK. OK. I understand that.

WILLIAMS: Exactly. There you go.

KELLEY: I respect that of course.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah. It's just that simple.

WILLIAMS: And I'm not trying to --

KELLEY: Maybe I could ask --

MUHAMMAD: You could be hearing like, you know, we can just pop and blow up and give it all.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: But then like, you just — it depends on the individual --

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: — which is why some people don't have those sort of --

KELLEY: Yeah, I know. I get that. Then maybe I can ask some question to help clarify for people --

WILLIAMS: Go ahead.

KELLEY: — who don't know who you guys are talking about. So would you prefer — are you asking that people evolve or that people stay within?

WILLIAMS: I'm asking that people evolve. You mentioned Octavia Butler earlier, right?

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: She has this book called Imago. And in this book — it's a really interesting idea that's in this book. In this book, it's the future, and humans, like our shape has evolved. We have more than one arm — we have more than two arms. We have extra limbs and antennas growing out of our head and all this stuff.

And at one point, it's explained how it happened. And what she explains is for that 100 years, we thought that we — that in fact, we thought that the answer to cancer was burning it out, chemotherapy and all this stuff, and in fact cancer was our body attempting to evolve with the environment and the times. And because we would try to burn it out, it would kill us. If we had watered our cancer, then our organism would've evolved. And so in fact, this whole new humanity came from us learning that we needed to water our cancer instead of burning it away.

KELLEY: So does that then apply to people's fears?

WILLIAMS: Yes. You should face your fears.

It's like people who smoke weed and say, "Weed makes me paranoid." Like, weed doesn't make you paranoid. You're paranoid. You're paranoid. You're grounded in fear. You have all these fears running around you. Weed is showing you that it's there. If you want to enjoy your high, why don't you spend the time not high addressing those fears, so that when you get high, you can actually get high and not just encounter the fears that you allow to run around your head all the time without properly addressing them and annihilating them.

MUHAMMAD: Absolutely.

WILLIAMS: How about that?

KELLEY: Co-sign.

MUHAMMAD: I agree with that. Well, and I just take — nevermind. The same thing. Same thing.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, but that's what I'm talking about. That's what I'm talking about. Is that we have to find the courage to approach things, to step beyond our comfort zones at times. And I believe that there are some artists that do that and go further and go further, and they get more and more wild. Like Oliver Stone, whose first film was Conan The Barbarian, went from being that guy to Natural Born Killers to now this thing on Edward Snowden. He's gotten more courageous, rebellious, revolutionary in his work as time has progressed. OK?

That's what I'm talking about. Same thing with Leonard Cohen. We were talking — I'm talking about an artist who's like, "You know what? I ain't got nothing to lose. I'm gonna go further out." You have other people who's like, "You know what? I miss that old school, man. I miss that duh-duh-duh." And that's a choice. That's an idea too. But you can go further and further out. Bowie's a great example of someone who was like, "OK. Let's go further and further out."

KELLEY: I mean also there's this — like the idea of hip-hop as youth culture. There's been this idea, especially from, I think, the corporate side, that's like: don't — you don't know — you hit 40 and you've lost touch. You don't know what the kids want. You don't know what's going to move, and you need to get out of the way.

WILLIAMS: Look at Miles Davis' B****** Brew.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Look at — there's tons of artists. Maya Angelou never wrote a book until she was 42.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: You know what I'm saying? There's so many artists whose great moments occurred well after what we would allot as, "This is prime-time," you know?

KELLEY: In rap, there hadn't been models, because it's so young, generationally-speaking. You guys are doing it.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, exactly. That's the thing. The only other model is the other forms of music. But I mean, you can't tell me that André 3000 is not getting fresher, just like you can't tell me that Tip is not getting fresher.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: These guys are getting fresher with time. They're actually getting fresher with time. I've witnessed it. I'm like, "Oh my god." The sort of grace and understanding that these guys have with music and their ability to listen and to understand where words can go and how they fit and how they flow and how they fly and all that stuff, it's enhanced. So that you have someone like Kendrick, who is coming at it as a young kid, encountering — being allowed glimpses of how these things can happen.

That's what I see it as, even for stuff that I wrote I was younger. I was like, "I'm being allowed glimpses of this stuff." But now is my turn to earn it. To take it further, to keep on growing. What can I write that I understood where this came from that I wrote when I was 22? And now how do I keep on evolving that? And it's through what you're reading and who you're surrounded by and the conversations you have and what you're listening to and going further and further and further and further and further, you know?

Imagine — I mean, you make amazing music that comes from listening. You're a crate digger. Your mom, like you said, had collected records.

MUHAMMAD: Yup.

WILLIAMS: And at what point did the people around you start going, "Yo, play that again," and started preferring maybe to hear the older version more than they were into like --

MUHAMMAD: Absolutely. And even now, where I'm at now --

WILLIAMS: Exactly. Where you're at now.

MUHAMMAD: — just transitioning from Brooklyn to Los Angeles cause this is where I needed to be --

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: — for my level of writing and creative levels. It's taken on another plateau that I'm excited about. But I never stop listening. I'm always open to receiving that information. It's similar to what you were saying, just the experience in Africa and talking about some of the other cultures. These things have been around for thousands of years; it's just we — I don't know. We didn't channel it until whenever we channel it.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. Exactly.

MUHAMMAD: So which is the now? The future of what's happening right now.

WILLIAMS: And so you take that in, you listen, and it keeps you growing.

MUHAMMAD: Can I go back a moment just to the story a little bit? Why Burundi?

WILLIAMS: Well, my wife is from Rwanda.

MUHAMMAD: OK.

WILLIAMS: And I love listening to stories of that region and what have you. It's filled with horrendous stories and horrendous realities. One of the positive things I was able to take away from one of the stories I heard was how Burundi, specifically the capital Bujumbura, was a destination for many people in Central Africa, like we might dream of Paris. Like, "One day I'm going to go to Bujumbura. I hear the women in Bujumbura, the music in Bujumbura, the food in Bujumbura —" so I started imagining the idea of this place as a destination.

Also because Burundi has a very specific — has had a very specific effect on music. There is an album recorded in the '60s called Les Tambours Du Burundi, the drums of Burundi, which Johnny Rotten got his hands on and played for Adam Ant. And the rhythms from Burundi in fact laid the foundation of new wave.

KELLEY: Wow.

MUHAMMAD: Wow.

WILLIAMS: The whole new wave sound comes from Les Tambours Du Burundi. The rhythm section.

MUHAMMAD: Wow.

KELLEY: That's really cool.

WILLIAMS: And those types of stories are of course of interest to me. And so --

MUHAMMAD: That's — information is enriching, man.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. So for a few reasons.

Also because I'm from a place called Newburgh, New York. And it's about 16 miles from New York City with 30,000 people. And for the past 40 years, Newburgh has had the highest murder rate, crime rate, drug trafficking rate in New York state. It's the most violent place in New York state, more violent than any place in New York City. But most people never heard of Newburgh.

And I relate that to the idea of Burundi because we know — like if I say Rwanda, I know the first thing — "Oh!" I know what you going to say. If I say the Congo, you've heard of the Congo, but most people haven't heard of Burundi. It's like that Robin [Harris] — what was that? "The man sitting next to the man!" The idea of this place you haven't heard of. It kind of liberates the imagination.

Part of MartyrLoserKing was inspired by when I was listening to M.I.A.'s album back in the day, and I loved the line where she was like, "I put people on a map that never seen a map." And that was part of the spark of like, "Ah, I'm going to focus on Burundi."

Ironically, focusing on Burundi has been interesting because, right at the time I started mixing and mastering this album, conflicts in Burundi have arisen. And they're ongoing right now as their president Nkurunziza has basically changed their constitution and put himself in for a third term. And so protestors have been in the streets. Hundreds of people have been killed. Hundreds of thousands of people have fled the country for fear of violence and what have you.

And the instability in that region is totally related to the history of instabilities in that region, meaning what we know of Rwanda, what we know of Uganda, what we know of Tanzania, Congo and all that. It's all — it's the same people actually, as in their neighbor Rwanda.

So it's a frightening time for Burundians right now, and so it's crazy that I ended up writing a song about protestors in Burundi before the conflict happened in my imagined story. And by the time that song was released, or is released, it's simultaneous with what's happening in Burundi.

MUHAMMAD: Yeah, I actually thought it was specific to it, which is why I asked you about it. But that's heavy.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. Yeah.

KELLEY: Can I ask you about a line on "No Different?" When you say, "Too selfish to be free," what do you mean by that?

WILLIAMS: Oh. I mean we're self-consumed individually and as a nation oftentimes. We're self-consumed. We believe that we're the center of the world and what we're about is the center of the world. You know how much we miss out on just in musical innovation because we only listen to music that's in English?

MUHAMMAD: Oh, yeah.

WILLIAMS: You know how much we miss out on in terms of film because we think Hollywood is the place creating the best movies in the world? Like, are you checking the movies out of Russia? Are you checking the movies out of Poland? Out of Romania? Out of Senegal? Out of Côte d'Ivoir? Out of South Africa? There's a bunch of stuff that doesn't work in our industry that's working in the rest of the world, actually. You know what I'm saying?

MUHAMMAD: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: And we're self-consumed enough to think that we're operating from this plateau of freedom and all this stuff, and from the outside looking in, it's always really obvious and clear examples of the freedoms we don't realize that we're missing, you know? We think we live in the freest country in the world but that's just a motto. That's just a motto.

There are places where there are — you know, it's not to say that the idea of democracy is not evolving and struggling to evolve in all places around the world, but it is to say that in a cultural sense we're too self-consumed to really express the greatest freedoms in the world. Because there's a lot of times when you think you're expressing something without realizing what it imposes on another, and how it imposes on another.

And then individually — because that song, "No Different," is really a personal thing. It's really about that in the microcosm, in the microcosmic sense. In the same way that I can say all that I want about what I understand about the world and blah blah blah blah, but it doesn't make me any different. I'm an artist with kids who often time is too self-consumed to pay the right amount of attention to something, too concerned with how I'm gonna finish this or how I'm gonna pay for that or how I'm gonna do that to give the proper attention to this or that. Or to enjoy a moment because I'm stressing out about the thing that's coming up tomorrow and what have you.

So it's also about the simplicity of that. And that's what I'm talking about in that song, is, "I see that in you, just like I see it in me. You're no different from the way I am." You're no different from the way I am. We're both in this, and it's always a dance that we're doing of like, "Wait a second. Why am I sitting here stressed out? I'm in the room with the most beautiful person I know. And why am I not enjoying this? Why am I stressed about who I have to go see after this? Why aren't I living in the moment?" You know, all those things.

So that's where that idea comes from.

KELLEY: Thanks for explaining that.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

MUHAMMAD: So, it seems like you're restless.

WILLIAMS: Hm?

MUHAMMAD: Seems like you're restless.

WILLIAMS: You think so?

MUHAMMAD: I don't know. You're --

WILLIAMS: I mean, I'm restless in the sense that like — I have a lot of energy. That's true. And I have the support of friends and industry at times, or in certain ways, or to a certain extent. But I always feel like there's a lot more I could do with a little more support. And so I'm — if I'm restless, it's because — like, for example right now I'm working to fund this film that I want to direct.

And I have a pretty cool background, in terms of film and stuff that I've been able to write and get out there and all of that. It's a weird but interesting background, but it's still difficult, as you know --

MUHAMMAD: Yes.

WILLIAMS: — to garner the support that we need. And walking around with the mantle of a poet or "deep" or any of these things isn't always helpful. It's full of respect and critical acclaim, but there's also these categorical boxes that you belong in. Like for that moment — "Well, we're trying to have a party right now. We're not gonna put this album on."

MUHAMMAD: Right.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: And I'm like, "Actually, this is for the party."

MUHAMMAD: Yeah, I was thinking that.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, this is for the party, actually. But people place ideas and people and certain forms of expression in boxes. I'm dealing with a very periphery art form, poetry. This is part of the reason why I'm dealing with graphic novels and music, because the infrastructure will allow that much more than they will allow poetry. A graphic novel has much more chance than a book of poems.

Even though I can sneak — you know, and I was like, oh, wow, a graphic novel, I can sneak in — that can just be the graffiti on the wall, the backdrop in a panel where two characters are talking. But like the brand of — what's written on the T-shirt, the brand of the sneaker, the graffiti on the wall, the poems are everywhere. So I'm forced to maneuver.

So it's not that I'm restless. It's that I'm hustling. I'm hustling, b.

MUHAMMAD: I got you.

WILLIAMS: Hustling poems. I'm hustling amethyst rocks, you know what I'm saying?

MUHAMMAD: Well, we appreciate it, and I mean, I totally understand the challenge. I was gonna say struggle, cause it's not a struggle. It's just a challenge.

WILLIAMS: No. It's just a challenge.

MUHAMMAD: It's a challenge. And I totally identify with it. And if anything for someone who has such a brilliant mind, and I think a great — I'll say teacher, in a sense.

WILLIAMS: Thank you.

MUHAMMAD: Cause your music and your poetry definitely, even this conversation is like a professor. And so --

WILLIAMS: But they ain't offering me no professorships.

MUHAMMAD: But you know what though? But that's the challenge, and I think you've — like for an example, as you explained with putting together this graphic piece, it's just figuring out the formula to do what you need to do how you want to do it. And it's no different to what other corporations are so really great at, in figuring out a formula to help push their product.

WILLIAMS: Exactly.

MUHAMMAD: I know you wanted to ask about Holler If Ya Hear Me?

KELLEY: Oh, yeah. I mean, I have several more questions. First of all, if you could just say on our air what Holler If Ya Hear Mewas, because everybody thought it was a Tupac biopic. And it's their fault and it's journalism's fault.

WILLIAMS: Sure. Holler If Ya Hear Me — I'll tell you something you don't know and what most people don't know — was conceptualized by August Wilson, and August Wilson began working on Holler If Ya Hear Me with Afeni Shakur before he died. The great playwright August Wilson. And his assistant took over the job after he died, and worked with Kenny Leon in bringing this play to life.

And what this play is and what August Wilson was working on and Todd took over was taking all of Tupac's lyrics and concocting a story, restricting yourself only to the characters that he mentioned in songs and to lyrics that he said, or used in songs. So just it's like if I say, "OK. I want you to write a story, but I'm gonna give you a book and every word you use has to come from this book." And so that's what it was. "Brenda's Got A Baby." So, OK, there's a character named Brenda. OK. And she has a baby. So you're just playing with all these ideas.

But no, Pac is not in the story. It was a story of a guy who gets out of prison and is trying to make a change in his life, but gets caught up, you know, out there. And right at the moment where you think that, oh, s***, he's about to get caught back up in the old thing that he was, he finds, re-finds, the courage and the wisdom that he encountered while he was in prison, and instead ends up changing the community by the decision that he makes in that moment of crisis.

And so it's about that. It was a musical. It was on Broadway. It was produced by Eric Gold, and it was directed by Kenny Leon, and it was extraordinary. It was an extraordinary experience for me, primarily because my background is --

KELLEY: And you starred in it.

WILLIAMS: Yeah, I starred in it. And my background is evenly tiered between hip-hop and theater. I started both the same time, when I was eight years old. I heard T La Rock, "It's Yours," and I took a class at my school called Shake Hands With Shakespeare and got cast as Marc Antony in Julius Caesar. Same year. And so by the end of that year, I was trying to write rhymes in old English.

KELLEY: Yeah, this very neatly brings me to my follow-up, which is: what are your observations and feelings about Hamilton?

WILLIAMS: Ah, man. I haven't --

KELLEY: And its success, its reception.

WILLIAMS: Ah, I think it's wonderful. I think it's wonderful. I actually have not seen Hamilton.

KELLEY: OK.

WILLIAMS: Except for I saw Lin-Manuel perform — we were both invited to the White House in 2009, and he performed what he was working on then, which was a few monologues from Hamilton.

KELLEY: Right.

WILLIAMS: And it was extraordinary. He is extraordinary. So I think it's amazing. I think it's amazing what he's doing.

If I were to make any parallels or connection between what's happening in Hamilton versus what happened with Holler If Ya Hear in terms of the hip-hop musical on Broadway, I would say that, you know, our story was about gun violence happening in the Midwest, right? We finished the play the week before Michael Brown was killed. And that's what the play was about. That's what happens in the play. That's what the play was about.

People coming to Broadway were choosing between Rocky The Musical, Kinky Boots and that. And even the people at the ticket booths out there were like, "Yeah, it's a great play. It's a bit of a downer." Cause people would leave crying, like when Sarafina!was on Broadway. People would leave crying. Madonna's in the front row, crying. Harry Belafonte's there, crying. Whoopi Goldberg's there, crying. Anybody who came would be.

And so we're at a point in the thing in our relationship to art in this country where we really have aligned it with escape.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: And if you're dealing with a play about gun violence in the Midwest right at a time where it's really going down, stop-and-frisk, and all those things that were happening in New York right at the point when the play was going on. That play did not provide the escape. What it provided was insight, revolutionary insight, into what was going down. But nah, there was no escape in that play.

Like, the play began with me coming down from the top of the theater in a jail cell. Coming down over the audience, in a jail cell, going, "They got a n**** shedding tears." It was too hardcore for Broadway. It was basically just too hardcore.

Hamiltonis fun, innovative, a refreshing look at history and diversity and duh duh duh duh duh. Like, that's its brilliance. That's its brilliance. But this was more like Do The Right Thing. You could leave the production of Holler If Ya Hear Me and holler at somebody, for real. Like, people were screaming. The last show we did, people were upset in the aisles like, "This is what we need! This is what America needs. They don't need to close it." People were going crazy. People were going crazy.

And it's that. Like, nah, it was touching on the pulse of something. And so that's story behind it. No, there was no Tupac character in that play. It was the spirit of Tupac. And that's why his mother who was a producer on the play was there like, "Tonight, revolution is happening on this stage." It's the same thing Harry Belafonte said to me when he came to see the play, more than once. And he was like, "Yo, you got a hard job here, dude. Cause you're taking something that is very politically poignant, and you're placing it in a Eurocentric context," meaning the Great White Way. He's like, "Phew. Wow." No, that thing was powerful.

KELLEY: So, as somebody who — and I would like to tip my hat to Rob Kenner for this question, Rob Kenner of Mass Appeal — so, as somebody who — so Slam. Slamis based on the life of Bönz Malone who's writing while in Rikers part of the time, learning while he's locked up. How did that role affect your relationship to writing around hip-hop, hip-hop culture, black culture?

WILLIAMS: Well, I was already writing around that stuff way before that happened.

KELLEY: I'm trying to get your perspective on rap journalism over the past — I don't know — 20 years, really.

WILLIAMS: Ah.

KELLEY: So maybe that's a simpler way to just ask.

WILLIAMS: Hmm. On rap journalism. Well, I've always been a fan of many a rap journalist and the time they take to digest and critique. I think of someone like Chuck Creekmur. I think of the old school heads like Greg Tate or Nelson George, dream hampton, even Kevin Powell. There were some great people that were really dissecting the culture and introducing it to the public in intellectually clarifying ways. I thought it was really fresh over the years.

In terms of where it's gone, I have no idea. I may have reached a point where I don't — it's rare for me to read too many articles on an artist more so than just listening to an album and making my own decision.

KELLEY: It's really upsetting to me that that work is not useful to you.

WILLIAMS: No, I think the work — it's hard to say. I mean, for example, I was excited about Medium and Cuepoint.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Because, for once, I felt like the writers were allowed to write about what they want to write about.

KELLEY: Sure.

WILLIAMS: Because there's also been this sense of — I don't know what to call it. I want to just call it d***riding, where --

KELLEY: That's what it's called.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. Where you got the sense that people writing for certain magazines were not allowed to be disinterested in certain things, that they weren't allowed to give a real critique, that they had to just — it's this populism, this thing of just like --

KELLEY: Chasing page views.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. And chasing clicks, and at the same time, just applauding this thing that everybody else is applauding, saying, "Hey, look! We're applauding it too."

And so it depends. I mean, it's reflected through every art form — and I include the rap journalism in the art form category — of places where it's like, I love the voices that don't conform. I love the voices that are really weighing context and the history of writing criticism and all this stuff. I think it's awesome, but I can't say that I read a lot of stuff — also because I'm sensitive, and so I dodge it for myself and then I dodge it for others, too, sometimes.

KELLEY: Yeah, totally.

WILLIAMS: But I think it's crucial. I think it's really important at the same time. And that's that. I don't know what else to say about that.

I think a Bönz, for example, Bönz is an amazing character. Bönz is quite the character, and has always been that dude who's had such amazing insight and a foot in so many worlds simultaneously. And it's rare for someone to have that sort of access and street credibility, simultaneously. It's wild. Bönz is an inspiration of mine.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. People ask me, "How is it that you can talk about these issues?" And like I said — my response is oftentimes, "How can you not?"

MUHAMMAD: Yeah.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: I don't know how much I could write about cars and girls. I'm just not certain how much I could do that. I take drugs. I don't know how much I'm gonna write about it, you know what I'm saying? Like, I'm just not — I don't know. I don't get it, other than, OK, that's what sells.

So those things are cool, but I understand — I know the second, the first time you mention, you know, popping a molly in your article, you're doing that for — to give this sense of credibility, of like, "Yo, I'm just like you. I'm a regular dude. I'm into the same stuff as you. You should check me out because I'm just like you, man. I'm not pushing it in any major way. I'm doing the same sort of stuff you're trying to do. I'm trying to get a VIP pass. I had taken a few pills." That's that article, right?

KELLEY: Yeah, yeah.

WILLIAMS: "I had taken a few pills. I was feeling good. Duh duh duh duh duh. Duh duh duh duh duh." So I applaud that sort of sensibility at times, not when it's overdone.

KELLEY: Understood.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. But I can see it for what it is. I can see — I mean, I use the same thing sometimes when I'm writing. You know, that this is a moment — this a great moment for me to say something that will be a reference. I mean, I could do it in an interview, right? I can reference Young Thug, so that people who like Young Thug could go, "Oh, OK. He likes some of the stuff that I do like as well." We all play these games, especially if you're writing. You're aware --

KELLEY: You've been talking about Young Thug for like two years in interviews, so --

WILLIAMS: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Because I'm sincerely into all that stuff.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: For me it started with Project Pat, when I was — because I was in New York surrounded by — well, I really wasn't in New York, but I was hanging out with a lot of New Yorkers who were, you know, restricted to — and I'm guilty of it, being restricted to liking the stuff where the content spoke to what they understood.

So New York cats were like, "Southern cats aren't even saying nothing." And for me it was like, "It's not what they're saying; it's how they're saying it."

MUHAMMAD: How. Yup.

WILLIAMS: Do you hear the way he's approaching this beat, dude? Do you hear the way — that's what's interesting. Forget — and I'm a victim of that.

I'll tell you the worst story of my life, which I've told before. But it's like one of the saddest moments for me, is when I was doing my first album, with Rick Rubin, and he sent me a bunch of DJ Screw mixtapes. DJ Screw was still alive. This is in 1999. And he's like, "Yo, this is what I think we should do." For Amethyst Rock Star.

And I put on the mixtapes, and all I heard was the content. And I had just signed to a major, and I had the all this pent up fear of like, "They're gonna try and change me." And so I heard the content and I was like, "Ah, there you go. They're trying to change me." And I didn't even realize that he wasn't talking about emulating the words that were being said. It was the style.

MUHAMMAD: Sound.

WILLIAMS: The chopped-and-screwed style.

KELLEY: Wow.

WILLIAMS: And I was like, "Nah nah nah, b." And I regret that, big time. He wanted to set me up to go in the studio with DJ Screw.

KELLEY: We would all be in a very different place if that had happened.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. So that's how I f***** up the world. Actually. We had to wait for like, "Mike Jones!"

MUHAMMAD: And there goes the answer to: so is there anything, lasting impression, that you've experienced that you want to leave with the kids to help give them some direction? I think that's it right there. You know, just to be --

WILLIAMS: Literature.

MUHAMMAD: Literature.

WILLIAMS: Literature. All I can say is this. Watch — over the course of year, make sure you watch at least four films that were not shot in English. Alright? Read — OK — let's say two books off of the top-seller list or something. That's fine. And then let's say, three or four more that you encounter from someone telling you about or what have you. And go through the genres. Like if you're into self-help books, that's fine. Do one or two. But try something in fiction. Find the fiction that speaks to you. Find the autobiography that speaks to you.

Like, there's something so rich and enriching from literature. Because then, you know, you also can figure out when you're actually innovating. There's so many times when you think you're innovating something, and literature's just a great example of that.

I can go back to the Rick Rubin thing, where I first started getting into like wanting to make punk music and picking up a guitar and stuff on my first album. And I'd be like, "Come to the house. I got this demo you gotta hear, yo. Come." He'd come by and he'd be like, "This sounds like you never listened to Rush or Black Sabbath, so you think you're doing something fresh, but anybody who listened to Rush or Black Sabbath ain't gonna be impressed." And I'm thankful for that type of hardcore --

KELLEY: I just liked your impression.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. You know? And so I thought I was innovating, but that was because I wasn't really checking on the references. I wasn't doing the homework.

MUHAMMAD: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: And so I had to go and do the homework. Find out what he was referencing. And then talk to other people. Play it with other people who were like, "Yo, have you checked this?" Before I know it, I'm backstage with The Mars Volta listening to CAN. Like, "Holy crap, prog rock. Holy crap. This is crazy." You know what I'm saying? And then just getting deeper and deeper into that stuff, so that then when it's time to make music again, I'm applying the stuff that now comes as an expression of the work that's been done, the research that's been done.

Anyway, I think literature is a really beautiful thing to have in your life. My son is 15 years old, and for the past six months, he's been reading everything by Kurt Vonnegut, Murakami, James Baldwin, Robert Heinlein, Patti Smith. He read Just Kids and just now — and Ta-Nehisi Coates. He's been — and it all started when I punished him. I punished him with a book, which was really smart.

KELLEY: What book?

WILLIAMS: Ta-Nehisi Coates. Cause he was 14 at the time, and he got in trouble. I won't say what it was, but he got in trouble. And I was like, "Ah, this dude said he wrote this book for his 14-year-old son." I was like, "You gonna sit in this room, you're gonna read this book, and you're going to write me a paragraph about each chapter." You know?

MUHAMMAD: Nice.

WILLIAMS: And at first, he started it off like, "You think his son read this book? His son didn't read this book."

KELLEY: Halfway through he's like, "My son didn't read this book."

WILLIAMS: And then halfway through, he's like, "It's pretty interesting."

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: He goes, "It's not as fun as Monster." He had read Monster Kody.

KELLEY: Yeah. Of course.

WILLIAMS: So he was like, "It's not as fun as Monster, but it's cool. It's interesting." And then he started getting more and more into it.

WILLIAMS: And then he was like, "Can you recommend something funny?" "Kurt Vonnegut." "OK."

MUHAMMAD: Nice.

WILLIAMS: It keeps on going.

KELLEY: Do your homework, kids.

WILLIAMS: Do your homework. Nah, we're telling you to check that out for a reason. There's amazing worlds to be discovered that will affect your approach to the world.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Big time. You know? That's all I am a reflection of, is the conversations I've had, the music I've listened to, the books I've read, the movies I've watched, which led me to new conversations, which led me to new references.

MUHAMMAD: Mm-hmm.

KELLEY: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: People being like, "What? You never checked this out before?" And then the next interview, I'm spewing out that name as if I've been checking it out for years, but I just discovered that fool last week. It's an ongoing thing. But then that makes somebody else come up to me like, "I heard that interview where you said you like that. You should check this." And before you know it I'm in like Russian literature from the 1300s. Like, "Oh, OK."

KELLEY: Yeah. It's the best.

WILLIAMS: Not necessarily that, but.

MUHAMMAD: That's what's up.

KELLEY: Word. Thank you for giving us so much of your time.

MUHAMMAD: Yes.

WILLIAMS: It's a pleasure to be here with you guys. It's a pleasant surprise to see these beautiful faces, and thank you for having me.

MUHAMMAD: Oh, thank you so much.

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

KELLEY: Thank you.

MUHAMMAD: It's an honor, pleasure.

WILLIAMS: Indeed.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))