New data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released last week show that during 2020, the height of the pandemic when many were purportedly staying away from others, rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) climbed sharply. That was after STIs in the U.S. had reached an all-time high for the sixth consecutive year in 2019, the agency said.

Now new preliminary data from the CDC shows that in 2021, rates of diagnosed STI cases “continued to increase during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, with no signs of slowing.”

North Carolina not only saw high rates throughout the pandemic, but for chlamydia, a common STI that can result in scarring of women’s reproductive organs and subsequent infertility, the state outpaced most of the rest of the country. North Carolina’s chlamydia rate was at 616.3 cases per 100,000 people.

While that was down from 676.6 per 100,000 in 2019, it still was high enough to push North Carolina from sixth in the nation for the disease to being ranked fifth, trailing Mississippi, Louisiana, Alaska and South Carolina.

In 2020, Black/African American men and women had the highest chlamydia rates (625.9 and 1,045.5 per 100,000, respectively) and accounted for 30.9 percent of people diagnosed with chlamydia, a total of 19,910 cases, according to state data.

“I think the data that we have for 2020, maybe even 2021, I think it may be under-counted,” said Christina Adeleke, from the North Carolina AIDS Action Network. “I think the pandemic could could impact the data in the way that knowing that, a lot of resources around sexual health were shifted to COVID.

Adeleke said that, but for COVID, the numbers would likely have been higher.

“There was fewer testing, like, folks weren't going in as much,” Adeleke noted. “A lot of that infrastructure wasn't operating as robustly as it is now.”

UNC medical school researcher Arlene Seña-Soberano is an infectious disease physician who studies STIs and sexually transmitted diseases. (Researchers note STIs refer to infections, while STDs are the diseases that those infections produce, which are often more complicated to treat.) She said that during the pandemic, there were also shortages of the materials to test for STIs.

“There was sort of a nucleic acid amplification test for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and some of those kits were being used for COVID testing,” Seña-Soberano added. “I recall, we were trying to figure out where we can get more tests to provide that to our patients.”

“Due to COVID, there were limited resources for what we call surveillance,” she added.

Race, poverty, gender affect rates

In North Carolina, rates of other sexually-transmitted infections crept up, along with the rest of the country.

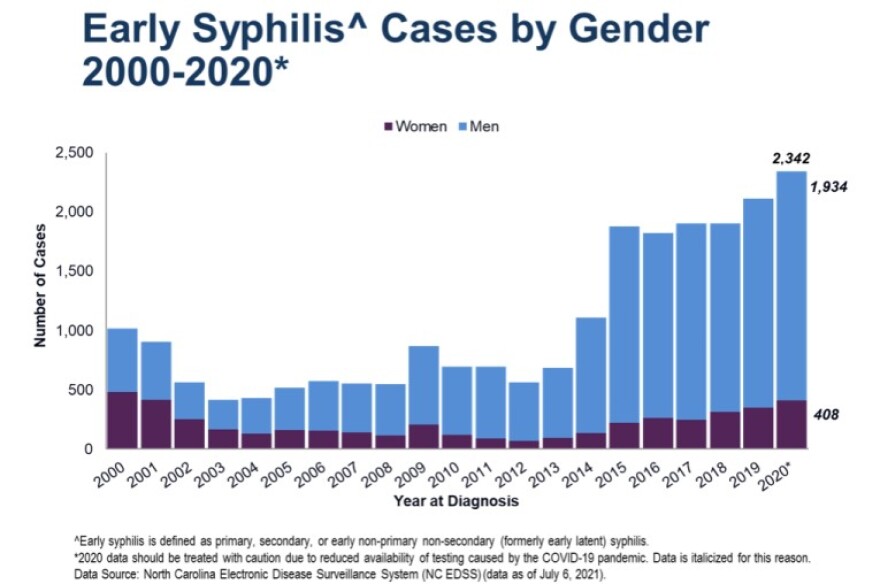

Syphilis continued its climb in North Carolina. In 2003, the state saw fewer than 500 cases, but numbers started to really surge in 2015, and by 2020, the state reported 2,342 cases. That translated into a syphilis rate that went from 10.8 cases per 100,000 in 2019 to 12.6 in 2020.

About eight in 10 of those cases in both years were diagnosed in men who have sex with men. About half of the overall cases, 613 out of a total of 1,263, were in Black men.

“There are some cities or parts of the state like Charlotte, like Raleigh, that are disproportionately impacted and have significantly high STD rates for even the country, not just the state,” Adeleke said. She noted that Charlotte, again, had high rates.

But STIs are not only an urban problem. Counties such as Cumberland, Vance and Martin counties have higher rates of syphilis than urban counties such as Wake, Forsyth and Buncombe. Some of those rates are a function of poverty, Seña-Soberano explained.

“The truth is that poor people have worse access to health care in the United States,” she said.

Seña-Soberano pointed out the effects of racism on the infections. Many of the counties with higher rates of STIs are counties where there are more Blacks and Latinos.

“Racism does affect health rates and in many ways, including people not being used to being served by the health care system, so therefore not reaching out to it, maybe, as fast as you do if you are used to being served by it,” she said.

Access to care was also cited by Erika Samoff, who leads HIV/ STD surveillance at the state Division of Public Health.

“Access to health care for young men, in particular, who currently don't have access to coverage, where young women if they get pregnant or are raising children, they'll have some access to Medicaid coverage, but young men just don’t,” Samoff said. “If you ask me, like asking what stops us from going around in this circle, better access to health care, especially for young people who are having the most sex is really important.”

Medicaid expansion would help some of the people who currently can’t get treatment for an STI into regular health care, Samoff said.

While Samoff agreed the pandemic certainly affected STI rates, she said that funding gaps for public health over the past decade have also contributed to the increase.

“One of the things that happened is everybody who works for public health, including me, you know, including everybody, all we did was COVID for a while, because we didn't have any extra staff capacity,” Samoff said. “That happened across the board, at every clinic, at every health department.

“That lack of staffing that was already true before the pandemic, and then we all had to go work the pandemic definitely contributed directly to higher rates of STDs.”

This coming year won’t see much of an uptick in public health funding, despite the continuation of a global pandemic. This past year’s state budget kept funding for public health preparedness flat at $2 million for North Carolina.

Passed on at birth

Samoff noted that syphilis rates tend to have the largest swings in incidence in a given area, in part because it’s really easy to treat when it’s a new infection and contact tracing can stop the spread in its tracks.

Nonetheless, North Carolina has had an uptick in cases of congenital syphilis, when a baby is born with the disease which has been passed on by a mother with untreated disease.

In North Carolina in 2020, there were 31 cases, compared to 19 cases in 2018. Two of the 2020 newborns died as a result of the infection. Others born with the disease can have jaundice, bone and joint deformities, as well as eye and ear nerve damage.

Good prenatal care should also result in fewer cases of congenital syphilis, Samoff said, with three tests being done over the course of a pregnancy.

“There is no need for anybody to suffer from congenital syphilis,” Samoff added. “What happens is that women don't get adequately tested. So that either a woman's never tested for syphilis during her pregnancy, or she's tested at the beginning of her pregnancy, like the first prenatal visit, but not again after that, until birth when it's too late. Or she's tested, but she doesn’t get treated for whatever reason.”

Sometimes it’s an access to care issue, she said. Sometimes it’s because a prenatal provider doesn’t have a high enough “index of suspicion” to test for syphilis, something that happens when caregivers make assumptions about a patient.

Education, real talk about sex

Rates of other gonorrhea went from 254.3 cases per 100,000 people in 2019 to 264.3 cases per 100,000 in 2020, with a total of 28,014 cases that year. Preliminary state data show that there were a few thousand fewer diagnosed cases of gonorrhea in North Carolina in 2021, although rates have not yet been calculated.

Adeleke said that she also thought that numbers of cases would climb again in 2022, as people get back into more routine testing and treatment.

“I feel like even if COVID didn't happen, I think we would be having this conversation, unfortunately,” Adeleke said.

Aside from everything else, she said there needs to be more education, more outreach to the populations most at risk and less stigma around talking about sex in order to get STI numbers under control.

“Not getting sex ed, or being prevented from giving comprehensive sex ed in some school districts or counties, you know, that doesn't come without consequence,” Adeleke said. “I think with this issue with it being around sex, unfortunately, like, we’re gonna have to work to reduce the stigma around sex and normalize talking about sexual health as a part of your overall health and well being.”

“The reality is STDs and STIs are out there,” Adeleke added. “So being able to at least first start the conversation and just normalize incorporating, you know, good sexual health practices, whether it be consistent testing, using condoms, utilizing other prevention measures.”

Samoff said that STDs are common for a reason.

“People will have sex and they will have unprotected sex, because that's how humans are, it feels really good,” Samoff said.

“So do we ever get to like zero transmission? No, because people have sex. So what we need is rapidly available treatment that's rapidly effective.”

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

North Carolina Health News is an independent, non-partisan, not-for-profit, statewide news organization dedicated to covering all things health care in North Carolina. Visit NCHN at northcarolinahealthnews.org.