Updated March 8, 2022 at 9:00 AM ET

When Brandon Jackson stood trial in Louisiana for armed robbery in 1997, two of the 12 jurors voted to acquit. In almost every other state, a non-unanimous jury would have resulted in a mistrial. But in Louisiana, a century-old law from the Jim Crow era allowed the split-jury decision to result in a conviction.

Louisiana voters approved an amendment that repealed split-jury convictions in 2018, and the change went into effect in 2019. The Supreme Court ruled these types of convictions unconstitutional in 2020, but those decisions didn't apply retroactively, so Jackson stayed in prison.

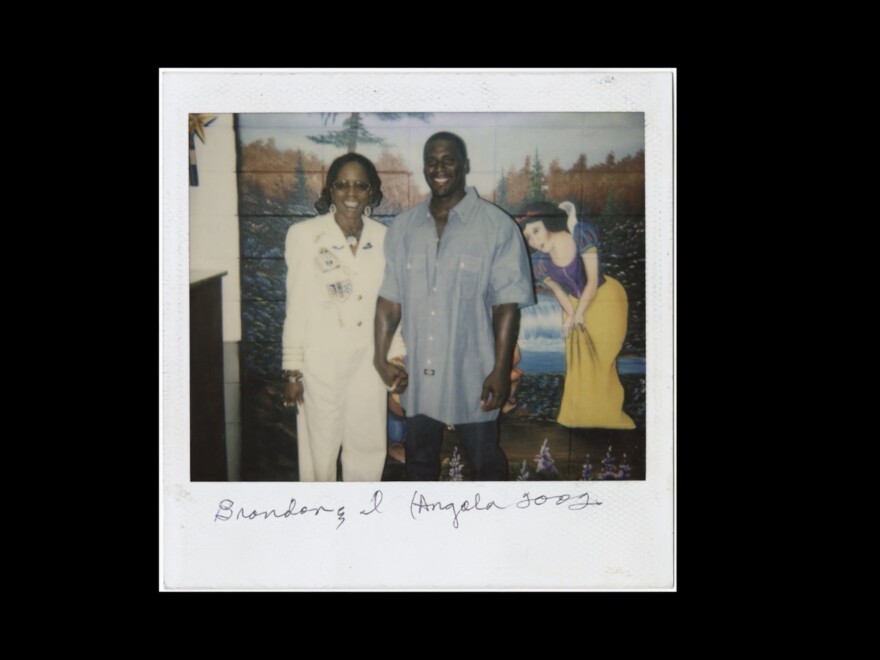

He was finally released on parole last month – after spending 25 years in prison. He said he feels blessed and joyful to be reunited with his mother.

"I'm just thankful to even be here," Jackson said. "Even just to sit at the table and drink coffee and do our Bible study together."

Jackson also said he's struggling to catch up with how much the world has changed while he was in prison.

"We went to a store and I didn't know– I stood there for maybe 30-45 minutes waiting on the lady to come check the items out," he said. "I didn't know that we are able now to check our own items out," Jackson says. "So when she showed me, I was blown away."

Jackson has maintained his innocence since his conviction. The state's case against him relied on the testimony of a man named Joseph Young who ended up changing his story a couple of times and ultimately testified against Jackson in exchange for a lighter sentence.

Jackson said he doesn't hold any grudges.

"I'm not even mad about it. I'm not angry about it," he said. "I think God allowed that thing that happened to me because he got something that he wants me to do and I'm going to fulfill it."

There are about 1,500 prisoners in Louisiana who were convicted by split juries and are still in prison. About 80% of them are Black, according to a 2020 report by the nonprofit Promise of Justice Initiative.

"All I can think about is the men that I left behind that's incarcerated under the same racist law that I incarcerated on. That's my fight," Jackson said.

But Jackson is also learning to savor the small joys of freedom, like simply going outside.

"We had a little rain, so I just walked in the backyard and just stood in the middle of the backyard," he said. "I wanted to feel God's tears just pour on me, so I just stayed there."

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.