President Biden took office a year ago promising to focus on the domestic crisis of that moment — the COVID-19 pandemic that was killing tens of thousands of Americans each week, confining millions to their homes and hobbling the world's largest economy.

Implicit in that promise was the unavoidable corollary: American involvement in other parts of the world would have to take a back seat to the domestic crisis at hand.

That is, until the reckoning in Afghanistan intruded, and before the Russians massed armored divisions on their border with Ukraine.

Biden now finds himself in the grand tradition of new American presidents who have made much the same promise but struggled to keep it. From George Washington's famous warning against "foreign entanglements" to Donald Trump's mantra of "America First," the pledge to prioritize domestic concerns has been almost as constant as the oath of office itself.

But far more difficult to keep.

Washington himself had no sooner taken that oath than the French Revolution caused convulsions on both sides of the Atlantic. Washington knew how much the French had assisted in his own military success, and also how close his fledgling nation was to renewed war with the British. Yet he held out for neutrality so he could concentrate on defending frontier settlements and federal taxing authority closer to home.

His successor, John Adams, had planned to follow Washington's lead before being derailed by a bit of intrigue known as the XYZ Affair (the letters were code for the names of three French diplomats engaged in a secret correspondence). American envoys trying to negotiate with the new revolutionary government in Paris were met with demands for money. Sentiment in the U.S. turned against the French and an undeclared war ensued on land and sea (sometimes called the Quasi-War). The U.S. bulked up its army and navy and an anti-war movement began in the brand new "Democratic-Republican Party" of Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson was himself a farmer and a believer in the agrarian economy. But when he became the third president, he promptly had to deal with pirates preying on U.S. ships in the Mediterranean Sea and the ongoing struggles between France and the rest of Europe. Unwanted as these and other imbroglios were, Jefferson took advantage of a cash-strapped Napoleon in 1803 to make the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the land mass of the U.S. for the bargain-basement price of $15 million.

You could say that was a bit of foreign policy that worked out well on the domestic front. But most foreign involvements have not be so fortuitous.

James Madison, the fourth president, had to deal with war drums along the frontier and also the return of British redcoats, who burned the Capitol and the White House in the War of 1812.

James Monroe, the fifth president, put forward his famous doctrine against European powers seeking new colonies in the "New World" — an effort to preserve a sphere of influence for the U.S. and minimize conflicts with foreign powers.

Turning inward

Monroe's time in office was sometimes called the "era of good feeling," if only in contrast to the tumult that preceded it and the descent into civil war that followed. From the 1820s on, from John Quincy Adams through Abraham Lincoln, the issue of slavery would overshadow all other conflicts, foreign and domestic.

The one "foreign war" in those decades was fought with Mexico and it was largely about territory – including much of what Americans have since regarded as America – Texas, California, Nevada, Utah and parts of four other states.

It was not until the end of that century that a foreign involvement would again play a central role in U.S. politics. President William McKinley came to office in 1897 intent on the substantial economic problems of his day. But that same year a rebellion against Spain in Cuba heightened tensions between Washington and Madrid. The U.S.S. Maine was dispatched to visit Havana's harbor, where it blew up in 1898, killing 260 on board.

Many in America blamed Spain, and McKinley was unable to resist the war fever. When the brief war was over, Spain had lost much of its remaining empire, and the U.S. had become something of a imperial power.

The rush of the 20th century

Since then, few U.S. presidents have been able to hit the hold button on foreign crises. Theodore Roosevelt, who had made a name for himself as a cavalry officer in Cuba, boldly seized territory for the Panama Canal and pursued "gunboat diplomacy" in Latin America. He also inserted himself as a peacemaker in ending the Russo-Japanese war in 1905 (for which he won the Nobel Peace Prize).

But the real plunge into the deep end of the foreign policy pool came a decade later. Woodrow Wilson was in the White House with historically ambitious plans, including a progressive income tax, and would eventually support women's right to vote. But his larger agenda was undermined when the First World War began in Europe and when the sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine started building pressure for U.S. involvement. The U.S. eventually joined the war against Germany and its allies, and thereafter Wilson not only attended the peace conference but tried to dominate it. Ultimately, his enthusiasm for a League of Nations was not shared by the Senate and the U.S. never joined.

For most Americans, the 1920s included a welcome surcease from world involvement. But the end of the decade brought a global economic depression that led to damaging trade wars and the self-destructive Smoot-Hawley Tariff in the U.S. The depression got worse, Franklin Roosevelt got elected president in 1932, and the focus remained on the domestic front for another decade. But war had returned to Europe in 1939, and the isolationist sentiment in America did not survive the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in late 1941.

The Cold War

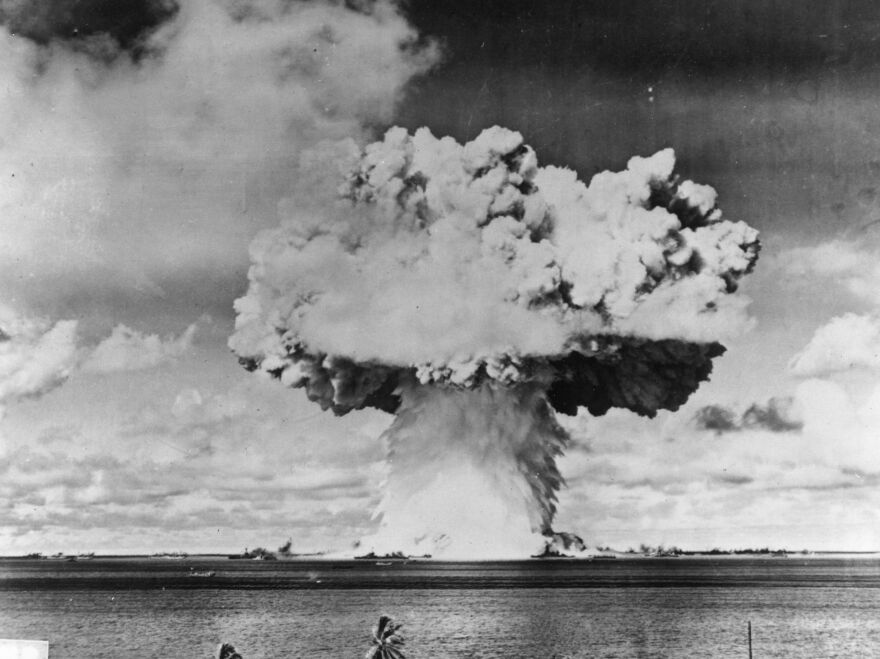

The U.S. emerged from the Second World War as the leading military and economic power in the world, its homeland unscathed by the war and its arsenal replete with the only nuclear weapons on the planet. But the Soviet Union had occupied much of Europe and was intent on maintaining a defensive sphere of influence there. In China, a long-running civil war was won by the Communists. Soon, people in the U.S. were obsessing about what many called "the global Red menace."

In this period, Harry Truman became the first U.S. president to take office in the midst of a war (succeeding upon the death of Franklin Roosevelt) and initially had little time for anything else. He saw that war through to its conclusion, including the use of two nuclear bombs, then mounted a stiff resistance against the ambitions of Russia and China. The U.S. entered the war between North and South Korea in 1950 to preserve the anti-communist regime in Seoul but the war dragged on without a conclusion.

In 1952, former World War Two commander Dwight Eisenhower was elected president largely on his promise to "go to Korea" and straighten things out himself. It was a clear break from the longtime tradition of playing down foreign affairs on the campaign trail.

When President John F. Kennedy opened a new national era in the 1960s, he was promising to "get America moving again" in an economic and psychological sense. He hoped to be able to keep that focus, but was immediately confronted on several continents by the Soviet Union. The Berlin wall went up in 1961, and an attempt to roust the communist regime of Fidel Castro in Cuba proved disastrous. A near-war crisis over the siting of Russian missiles in Cuba was perhaps the most enduring episode of Kennedy's brief time in office.

Vietnam and Iran

Lyndon B. Johnson became president upon the assassination of Kennedy in 1963. He immediately concentrated the emotional impact of that event on enacting some of his predecessor's agenda, including passage of a milestone civil rights bill. Johnson got that done, won re-election in a landslide, and came back to office in 1965 with plans for a Great Society guided by generous government spending and sweeping federal authority.

But from his early months in office, Johnson's attention had been divided. The anti-communist regime the U.S. had been backing in South Vietnam was losing. Johnson got Congress to give him authority to escalate the struggle in 1964 and used it aggressively in 1965. Before long that escalation involved half a million U.S. personnel on the ground. Casualties mounted. An anti-war movement arose and gained strength through the remainder of the 1960s, weakening Johnson's Democratic Party enough for Richard Nixon to win the White House in 1968.

Nixon campaigned on a promise to "bring us together" and an implicit promise to end the Vietnam War "with honor" if not necessarily with a clear victory. He, too, wanted to tackle the domestic unrest that had become characteristic of the late 1960s. But unlike many of his predecessors, he knew he had to deal with foreign policy first.

He dedicated most of his first term to re-ordering relationships with Russia and China to make a withdrawal from Vietnam possible. In the end, beset by scandals from his re-election campaign in 1972, Nixon resigned less than halfway through his second term. His was the rare case of the foreign-policy oriented presidency whose plans were frustrated by domestic crisis.

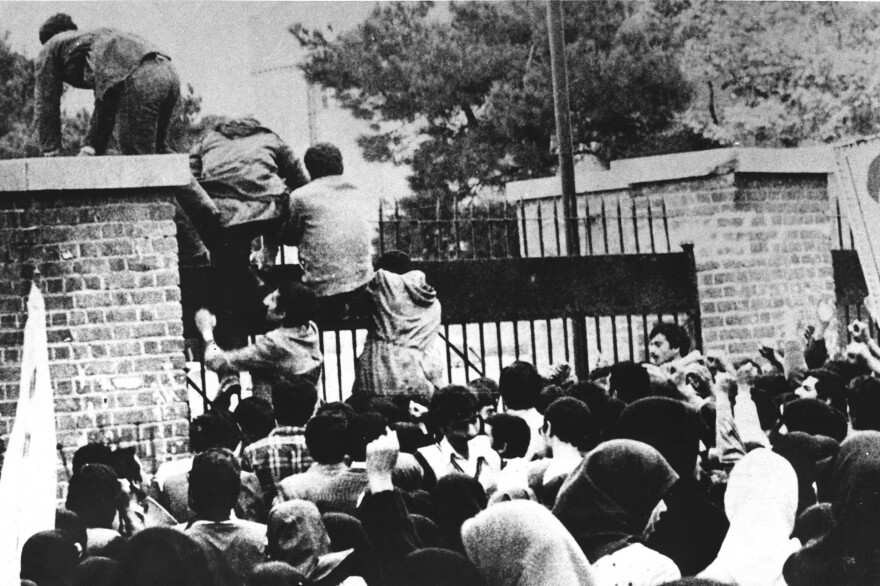

The next elected president, former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter, said little about foreign policy in his rise from relative obscurity to the Oval Office. But in office he had his high and low points defined by international events. He managed to negotiate a lasting peace deal between Israel and Egypt (the Camp David Agreement of 1978). But he ran aground on the Islamic fundamentalist revolution in Iran the following year. After Carter allowed the former shah of Iran to enter the U.S. for cancer treatment, radical students in Tehran seized the U.S. embassy there and held more than 50 Americans hostage for 444 days, releasing them the day Carter left office.

Reagan and the Evil Empire

Ronald Reagan did not beat Carter on foreign policy alone, by any means. But he was fortunate to arrive at a time when Iran and other hot spots around the world were cooling. The Soviet Union, which Reagan had inveighed against for decades as a conservative commentator and governor of California, was lurching toward its final break-up when he was president. It was difficult for Russia in that era to match Reagan's increases in defense spending.

Reagan generally enjoyed genial relations with world leaders, including with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, with whom he concluded an ambitious nuclear arms-reduction deal. Reagan also managed to minimize damage from an ill-conceived three-way deal to free hostages in Iran through a secret arms sale to that country (with profits secretly passed on to anti-communist rebels in Central America).

In the end, he could turn over the tiller to his vice president, George H.W. Bush, who promised to be "the education president" but wound up spending an extraordinary amount of his time on world affairs. He could bask in the glow as the Berlin Wall came down on his watch. He also enjoyed strong public approval for his takedown of a drug-dealing dictator in Panama in 1989 and his successful multi-national effort to drive Iraqi invaders out of Kuwait in 1991.

Still, Bush was distracted from his own domestic priorities often enough to allow Bill Clinton to defeat him in 1992 by promising to "focus like a laser" on the economy (which also came to mean health care). For a time, America's erstwhile enemies were over the horizon again. Foreign policy did not intrude until, in his second term, Clinton joined with NATO allies to resolve a war in the Balkans. Clinton was fortunate that no American personnel were killed in that brief war.

The War on Terror

George W. Bush arrived in the Oval Office in 2001 and devoted himself to two issues the elder Bush might have liked to have had the chance to pursue – a generous tax cut and an education bill negotiated with the Democrats.

But in the second Bush presidency, the world came calling in a way it had not since 1941. Suicide attacks by well-organized terrorists killed nearly 3,000 Americans in the World Trade Center in New York and at the Pentagon. Bush immediately pivoted to a "global war on terror" that would define his first term, help him win a second and ultimately trap the U.S. in the role of occupying power in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Campaigning not as an opponent of "all wars, just stupid wars," Barack Obama took over the White House in 2009 with the nation once again consumed with an immediate economic crisis (what would become the "Great Recession" of 2008-10). Eight years later, the U.S. was still stuck in its unwanted roles in Kabul and Baghdad and wrestling with successor terrorist groups such as ISIS in Syria and Africa.

A president without precedent

In a sense, Donald Trump brought his first foreign crisis into office with him, a holdover of the campaign, during which he had encouraged Russia to seek the lost emails of his opponent, Hillary Clinton. The Russians did not find those, but they did obtain thousands of emails sent by Democratic operatives during the campaign, which were subsequently published by Wikileaks.

The damage that did to Clinton is difficult to quantify. But its significance was magnified later on when U.S. investigators proved that Russian operatives, some robotic, had also been flooding social media platforms with anti-Clinton messages throughout the campaign year.

This led to a two-year probe headed by former FBI director Robert Mueller, which confirmed the Russian anti-Clinton interference but did not find evidence the Trump campaign itself had played a role in it. But soon after this crisis had subsided, a new one arose. It was learned that Trump had held up military aid to Ukraine while pressuring that country to announce an investigation into the business dealings of Hunter Biden, son of the former vice president who is now President Biden.

The House impeached Trump for that, but the Senate did not muster even close to the two-thirds majority needed to convict. Thereafter, Trump would continue to question the value of NATO and the U.S. commitment to defend western Europe.

There were plenty of other foreign issues in Trump's term. U.S. troops were still in harm's way in Syria as well as Iraq, and North Korea's dictator was warning he would arm his newest missiles with his newest nuclear warheads and threaten anyone in the Pacific region. Iran was testing the limits of the nuclear agreement it had signed with the U.S. and its European allies

In Afghanistan, nearly two decades years of U.S. military presence and all manner of aid had not established a government with enough public support to suppress a resurgent Taliban. Long a critic of "endless wars," Trump made a deal with the Taliban and set a date for U.S. withdrawal as of May 1, 2021.

But all these were issues Trump inherited from his predecessors and left to Biden. Trump's main foreign policy attitude was always to question orthodoxy and challenge existing arrangements and alliances, doubting or denying their value for the average American. If something did not benefit the U.S. at least as much as other nations involved, Trump saw it as contrary to his mantra of "America First."

For that reason, Trump's foreign policy posture remained among the more popular aspects of his presidency. And that has proven problematic for his successor, whether he tries to maintain what worked for Trump or to change it.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.