By the time a group of high school students showed up at Richard Moss' home in 1980, he was an old man in his 80s.

He was a master of shape-note singing — a remarkable old style of music he learned from his elders, who learned it from their elders in the mountains of northern Georgia.

The students wanted to document the tradition for their magazine, Foxfire.

Named after a bioluminescent fungus that glows in the hills of North Georgia on certain summer nights, Foxfire started in 1966, when an English teacher in Rabun County was having a difficult time engaging his students. Out of ideas, he let the kids design the lesson. They chose to publish a magazine that would document the mountain culture all around them.

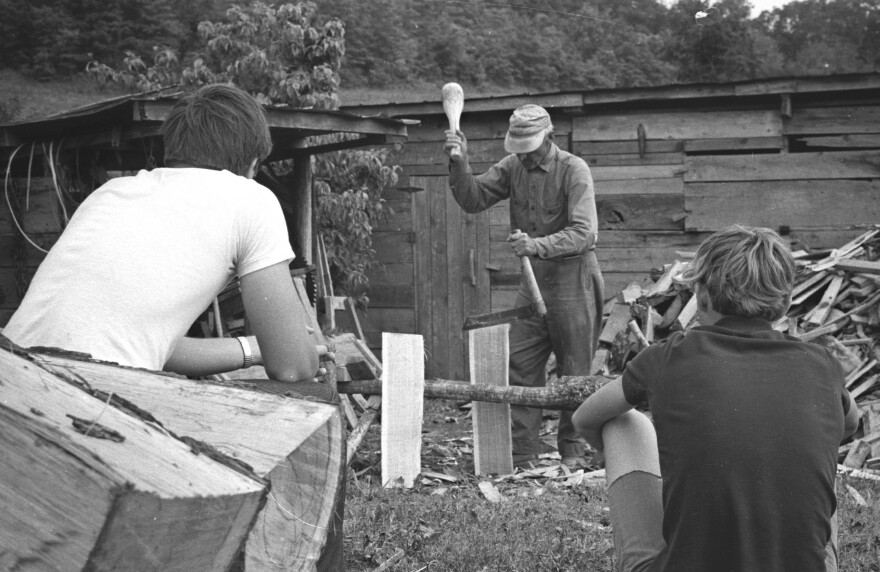

For 50 years, Foxfire students have recorded the disappearing traditions of Appalachia, and the stories of the region's mountain folks. They've told the stories of blacksmiths, moonshiners and woodworkers.

The program's impact has rippled across the country: Projects modeled after Foxfire have popped up in schools from Texas to Maine.

And the books that grew out of that student-produced magazine became national best-sellers — out of 21 Foxfire books, 20 are still in print. They sold so well that in 1974, the proceeds were used to buy land and create a museum in the mountains dedicated to preserving Appalachian culture, the Foxfire Museum & Heritage Center in Mountain City, Ga.

Set on more than 100 acres, the site is crisscrossed by walking trails and dotted with period buildings.

There's a wagon house, a blacksmith's shop, a gristmill and a church — all built or salvaged and reconstructed by students. For instance, student volunteers disassembled the 1800s gristmill, carried it to Foxfire log by log, and put it back together.

There are demonstrations in blacksmithing and basket weaving. It's a living, breathing museum, a home for traditions that are dying out — but worth preserving.

The culture of Appalachia is incredibly rich, says Barry Stiles, Foxfire's acting executive director.

"It's also a culture that's often misrepresented, a lot of stereotypes with mountain people," says 53-year-old Stiles, who has roots in the region. "And so by preserving the culture and presenting it, people become educated to the truth about mountain people."

He describes these mountain people as "very resourceful, self-reliant, hardworking, intelligent and with an amazing sense of humor" — people like Buck Carver.

"My dad was a moonshiner," says Carver's daughter, 59-year-old Kaye Carver Collins.

"When the men landed on the moon, my dad and another gentleman were out in our yard digging a big hole to put cases of liquor down in, and then they capped it off with a washtub that had grass growing in it," she recalls. "And you'd take these handles and lift the washtub up and the liquor was down inside the bank."

Kaye Carver Collins' connection to Foxfire isn't just through her father and her mother, Leona Carver, who was also interviewed by the magazine: In 1973, she was one of the high school students doing Foxfire interviews. She says the books struck a chord across America.

"No matter where you were from in this country, you could find somebody in that book that was like a relative of yours, or like your mom or dad," she says of the books' appeal. "It felt personal to everybody that read it."

Foxfire interviews have touched every aspect of life in this slice of Appalachia, from birth to death. Some are simply accounts of local lore: The first Foxfire recording is of a man who witnesses a bank robbery, while getting his hair cut.

Some entries read like a guidebook for mountain living: how to build a log cabin or split shingles. Others are words of wisdom. Students interviewed a woman they referred to affectionately as simply Aunt Addie, who told them:

I think how thankful people ought to be that they're living in this beautiful world. And I wonder how they can ever think that there is not a higher power. Who makes all these pretty flowers? We can make artificial flowers but they don't smell and are not as pretty as the flowers that we pick out there. We can't make flowers like the Almighty.

While anyone could conduct these interviews, a key part of the Foxfire philosophy is that local students — like 18-year-old Jessica Phillips, a high school senior — do the work.

"This program makes me appreciate that I can go and sit down with these people and just learn," Phillips says. "And make connections that otherwise I wouldn't make."

For instance, she recently attended the funeral for a man she interviewed last year.

Some people who grow up in small towns dream of moving to the big city. But Phillips wants to stay. Partly, she says, that's because Foxfire has made her appreciate that there's something special about this place.

And, she says, while her friends are busy tapping away at Instagram or Pokemon Go, her experience with Foxfire has taught her that it's OK to slow down.

"It makes you realize that you can take that time out ... and go sit on the porch with somebody and talk to him about their stories," she says.

Stiles, Foxfire's acting executive director, says he goes back sometimes and reads the transcripts of interviews that his grandfather and great-uncle did almost 50 years ago.

What stands out most from those interviews is the hardship. It gives him perspective.

"Sometimes I think I'm having a really bad day, and I think about some of the things people had gone through 50 years ago, 100 years ago, and I think, I'm just a whiner," Stiles says. "What am I complaining about? This is nothing compared to the flu epidemic of 1917 or even World War I or starving."

And yet, part of him longs for what has been lost. That's why he's here: to make sure it isn't lost completely.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))