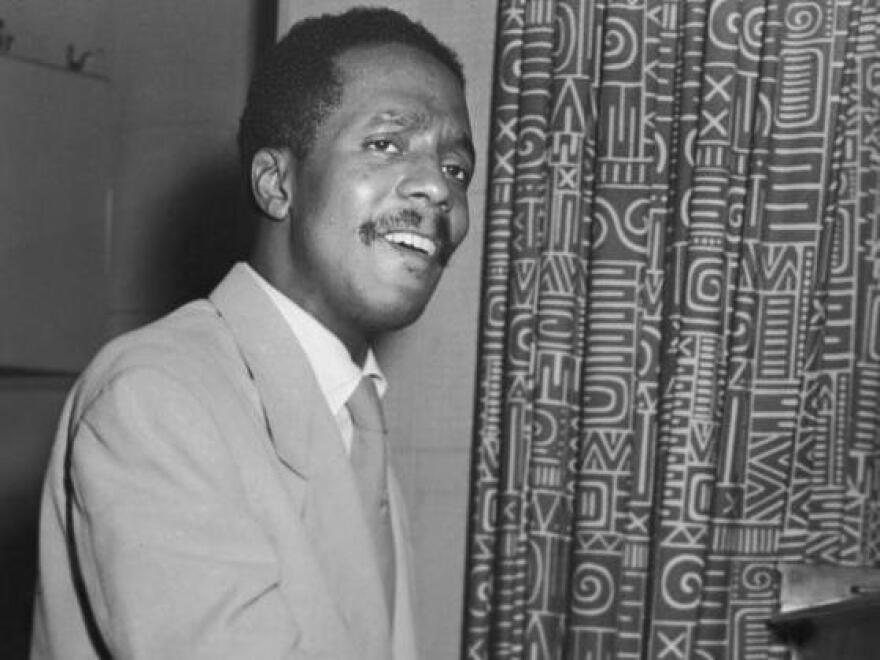

The great bebop pianist Bud Powell played several engagements at the New York jazz club Birdland in 1953. Parts of his shows were broadcast on the radio, and one listener recorded some onto acetate discs. A new collection of those recordings is out now: Birdland 1953 on three CDs from ESP-Disk'. The sound quality isn't much, but the music is terrific. The players with whom he worked there include bassists Oscar Pettiford and Charles Mingus and drummer Roy Haynes.

Powell had played Birdland before he opened there on Feb. 5, 1953, but this return engagement was a big deal. That very day, he'd been discharged from a state psychiatric hospital, after being committed for a year and a half following a drug bust. (Powell's mental troubles stemmed partly from a 1945 police beating in Philadelphia.) He was painfully uncommunicative face to face. But when he sat at the keys, it was a whole other story.

As with other versions of this material, the sound only gets cleaned up so far; filter out the surface noise and you also lose most of the cymbals. But Powell's piano punches through. His quicksilver lines could echo Charlie Parker's saxophone, breath pauses and all. Still, Powell's concept was deeply pianistic — he knew how to make the strings ring, and how to cover the keyboard. Older pianists accused bebop players of performing with only one hand. But Bud Powell's jabbing left is always part of the rhythmic conversation.

A recent biography of the pianist, the exhaustively researched and thoroughly depressing Wail: The Life of Bud Powell by Peter Pullman, spells out what a nightmare Powell's life was at the time. While hospitalized, he was subjected to at least a dozen insulin shock treatments. When he was released, it was into the custody of Oscar Goodstein, his legal guardian and business manager, as well as the manager of Birdland where Powell was appearing — shades of the old plantation. Then Goodstein pushed Powell into a sham marriage to a woman he barely knew. It didn't last, but Powell was hemmed in on all sides.

Powell named one evocative new tune "Glass Enclosure," either for the Birdland radio announcer's booth near the stage, or the apartment his manager warehoused him in, or maybe the invisible box that walled Powell off like a trapped mime. You can understand why Powell so needed to play, he'd nudge other pianists off the bench when he went club-hopping. The keyboard was the only place where he could fully express himself.

It turned out that 1953 was one of Bud Powell's most productive years. Besides his series of Birdland engagements, he had some out-of-town gigs, including a celebrated Toronto concert that reunited him with his bebop peers Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach. He also recorded a batch of material for the Roost and Blue Note labels, the latter released under the rubric The Amazing Bud Powell. The performances on Birdland 1953 confirm that that adjective was no idle boast.

Copyright 2021 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))