Every day in the streets of Baghdad, U.S. troops are subjected to random attacks by insurgents who easily blend in to the civilian population. Every car and truck on the crowded roads is a potential bomber, and any suspicious behavior can draw American fire. Innocent civilians often are killed, breeding resentment and sympathy for the insurgents.

One such fateful encounter happened a year ago, between two men, nearly the same age, from opposite sides of the world.

Romero's Call to Duty

Staff Sgt. Joe Romero shot and killed Dr. Yasser Salihee on June 24, 2005. The U.S. Army found the shooting justified under the rules of engagement. Iraqi witnesses saw it as murder. For the people closest to the shooting -- the soldiers and Iraqis on the street that day, the shooter and the victim's family -- this one incident had a profound impact.

Joe Romero, 33, grew up in Lafayette, La. His mother, Carrie Durand, says that when he was a boy, he wanted to be a soldier. His father, a pilot in Vietnam, died in a plane crash before his birth. Romero grew up to become an elite Army Ranger and sniper. He briefly left the Army, but after Sept. 11, he wanted to serve his country again.

He joined the Louisiana National Guard, 256th Combat Brigade, and arrived in Iraq in October 2004.

A dozen people NPR spoke to in the 256th described Romero as an excellent soldier.

"When you looked at him, you could just tell he was a man," said Pvt. Corey Prince, who served under Romero in Baghdad. "And he was intimidating … this guy would make you do more pushups than any drill sergeant you ever had. If something's wrong with you, he's gonna fix it. And he's going to make sure you remember to fix it the next time."

But Romero's military career would end in bitter controversy and a 14-month jail term. He was tried and convicted just a few days before the 256th left Iraq. This was not for the shooting -- but for the possession and distribution of drugs. He is still in military prison and is appealing his sentence.

Salihee's Call to Duty

Yasser Salihee, 30, was a Sunni physician at Baghdad's Yarmouk Hospital. He sported wire-rim glasses and a buzz cut, and was married to a fellow doctor; they had a two-year-old daughter, Danya. But when the chance came to translate for foreign journalists -- including NPR -- he jumped at it. His first translating assignment was in fall 2003.

At the time of his death, Salihee was working for Knight-Ridder newspapers and was receiving solo bylines, a rarity in the Iraqi press corps.

His widow, Dr. Raghad Wazzan, says that Salihee felt he was helping people by being a journalist.

"He told me many times, 'I hate medicine. I love being a journalist. I love making all the world know the truth of what is happening inside Iraq. If I stay a doctor, I'm doing just one job when an explosion occurs. If I do both jobs, I'm saving lives and telling people the truth,'" she recalls.

June 24, 2005

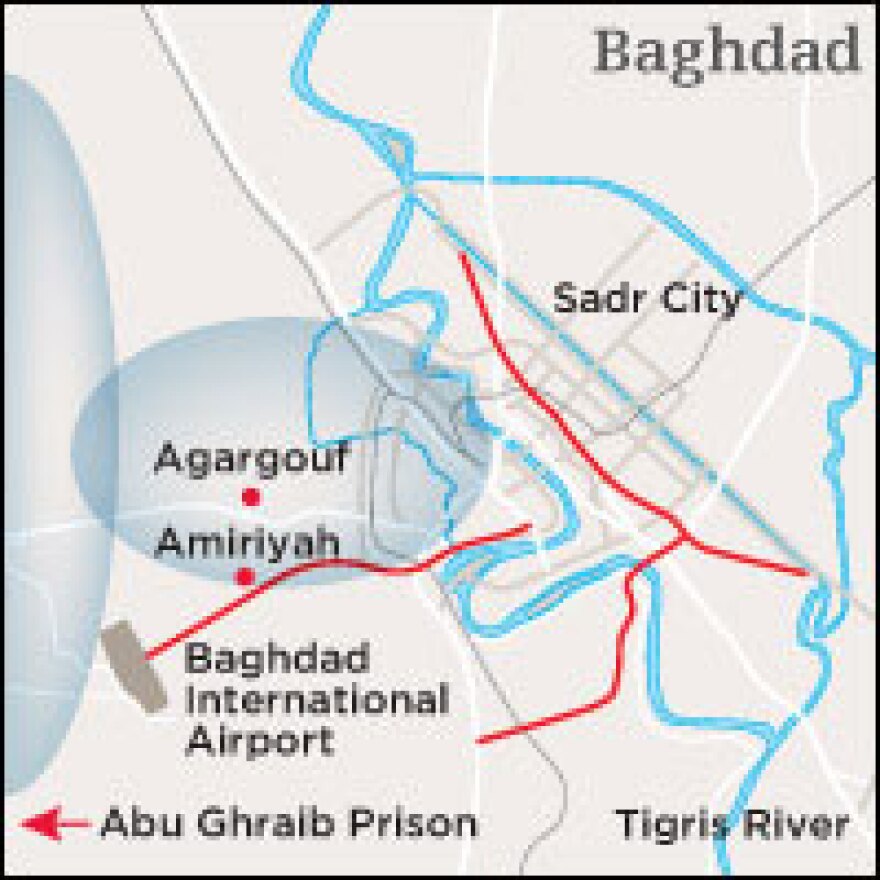

The Salihee’s moved to Amiriyah in Western Baghdad, a former stronghold for the regime. Neighborhood walls were painted with black slogans calling for the killing of Americans. Then came the morning of June 24, 2005. It was a Friday, the Muslim day of rest.

Wazzan remembers how the day started. She and Yasser awoke at 10 a.m. and ate breakfast. Then they got ready to go swimming at Al Alawiyah club. At the last minute, Salihee decided he wanted to shave his hair. He said he'd be back in 10 minutes. An hour went by.

About the same time that morning, a platoon with the 256th's Bravo Company, along with soldiers from the Iraqi army, rolled into Amiriyah. Staff Sgt. Romero volunteered to go along. He said snipers were not in demand in Baghdad, so he had been stuck in a headquarters company. He wanted action.

"I enjoyed going to work. I enjoyed doing my job. I enjoyed going out there. I lived for that rush to be out there. That's what I wanted to do," Romero said, speaking from a military prison in Ft. Lewis, Wash.

Four other members of that patrol who were contacted by NPR say they were edgy that morning. Just one day earlier, another soldier from the unit, and a friend of Romero's, had been seriously wounded by a sniper's bullet at a major intersection. When the patrol reached that same intersection that morning, another shot rang out. The platoon dismounted in haste and most of them headed into a nearby building.

Romero and his partner, Christian Jones, positioned themselves so they could keep watch on the street outside. Iraqi soldiers took up position across from them and quickly stopped one car with hand signals and shouting. Speaking on the phone from military prison in Ft. Lewis, Romero explained what happened next.

"Another car was approaching," Romero said. "We could see it way down the road. It was coming straight at us. We could tell it was coming at a rapid rate of speed. We started waving and pointing weapons to get it to stop. At that time, it didn't stop and I started making out the driver."

Romero noted that it was a single man driving a white vehicle, fitting the profile of a suicide car bomber.

According to Iraqi and American witnesses interviewed by NPR, the car was going 30 to 40 miles an hour and was about 100 meters away. Romero now had about six seconds to make a life and death decision.

Romero says that he and his partner, Jones, stepped into the middle of the street and fired warning shots.

"I know I shot toward the hood of the vehicle and in the front. Jones shot the tire," Romero said. "The vehicle is still coming at a high rate of speed. I make eye contact with the driver, he looks like he's crouching down, his hands weren't up, looked like he was hiding, vehicle kept coming. At this point, it's 30 to 25 meters from me when I had to fire my last shot and I took a shot at his head," Romero said.

The rules governing contact with civilians call for a gradual escalation in force: a warning shot, a disabling shot, and finally, the lethal shot.

Romero says he never saw Salihee hit the brakes after the warning shot. He says that when the car rolled past him, he saw blood as the driver's hand dropped away from his head. Air was hissing from the tire shot out by Jones.

Stores line the intersection in Amiriyah and shopkeepers have challenged Romero's version of events.

Discrepancies

Ice-seller Majeed Mahmoud Aboud, 24, told NPR that Jones and Romero took up positions next to his tiny metal kiosk on the corner. He and at least one other Iraqi witness say that the very first shot was the lethal shot.

"My mind is not like a computer but I can remember this," Aboud said. "We were waiting, it was a hot day and the Americans came in and they took the saw I used to cut the blocks of ice. I was chatting with the other shopkeepers when I saw the driver coming fast. There were four Iraqi national guards on the street. When the driver saw the guy, he tried to stop. But as he hit the brake, he was shot. In one or two meters, he stopped."

Clothing-store owner, Bahjat Adnan, 47, also witnessed the shooting.

"There were two kids in the middle of the street and they said 'Stop! The Americans are in the street and they will shoot you,'" Adnan told NPR. "This is what got my attention and made me turn around and look. The kids were about 10 or 12 years old. I heard three shots. The first one was when the car tries to stop. The car screeched to a halt. I know that it was just a civilian guy who got shot and I don't know why he got shot except that he was coming very fast."

A bullet distorted by the heavy windshield glass crushed the bones around Salihee's eye and made a gaping wound on right side of his head.

Others thought an Iraqi soldier might have fired the deadly shot, but Romero had no doubt that the bullet was his.

NPR retrieved the bullet from an Iraqi police station and hired an independent expert, who concluded that the bullet came from an M-14, the type of weapon Romero said he was using.

An Order to Leave the Scene

Members of the patrol say they searched the car, took pictures, and found no weapons or explosives -- only Salihee's press credential and his cell phone.

"They just left the body in the car and after 10 minutes, the whole unit left," store-owner Adnan said.

Romero and other platoon members say they were ordered to leave the scene, even after the platoon commander questioned the decision. Salihee's body was left behind in his car when the temperature was soaring above 100 degrees.

"We left the guy there like a piece of meat … like a bad guy," Romero said. "I didn't like it, I didn't understand it, I didn't believe it and I definitely didn't agree with it. That's probably one of the worst commands I've ever seen given."

Platoon members say that the order to leave the scene was given by a battalion commander whose code name was Bandit Six.

Lt Col. Daniel McElmore was the battalion commander that day. He says he does not recall giving the order.

"That does not sound like the way we conducted business in Baghdad," McElmore said.

At the scene, one of the eyewitnesses picked up Salihee's cell phone and started making phone calls. Dr. Raghad Wazzan, Salihee's widow, was the first to arrive. Aymen Salihee, his brother, was also summoned.

"When I saw the car surrounded by, I think, two Iraqi police vehicles, I just knew that Yasser is gone," Aymen Salihee said. "And I run to the car … Two guys try to throw me out and I pushed them away and I saw him … I couldn't open the door because they just stopped me. Everything changed in my mind and I couldn't think and I couldn't see my way. I think it's over for me because Yasser is everything for me. He's not just my brother."

After an hour or two, Iraqi police arrived. They made a rudimentary sketch, noting a skid mark on the road behind the car.

The Official Response

The shooting received international publicity. As in all serious incidents involving death or injury or major property damage in the 256th, an investigator was appointed. The investigator was Maj. Andre Vige, and his first duty was to offer condolences to the family.

"The tension was so thick, you could cut it with a knife. The elders of the family, I think they were not sympathetic towards what happened but I think they were sympathetic towards me for having to be the one to go there," Vige said. "And of course everyone wants to look at blame and place blame and that's understandable. I guess in a sense, you're looking for a magical answer to give them to make everything OK. But there is nothing. There's nothing that you can do. I mean we're human," he said.

Wazzan remembers the visit.

"When he come, he start to cry," she recalled. "He said, 'I'm sorry for what's happening. I'm sorry. I know your husband is so young.' He said, 'I'm so sorry for what's happening but what can I do?'"

Wazzan was not happy with the compensation paid for her husband's death: $2,500, the same amount the Army paid her for the car.

"They represent Yasser as a car," she said. "They represent him as a machine! I'm telling them, 'He's a father. He's a son. He's a husband. He's a doctor. He's a journalist.'"

Yet Vige found that the shooting was justified, and the only person at fault that day was Yasser Salihee.

In a letter sent to NPR, Vige wrote, "I will state for the record that Mr. Salihee would still be alive if he had been more attentive and in tune with his environment. Tragic as it may be and with the sympathy I hold for his family, I must admit that he was not very wise in his decision-making process on the day of the shooting. Mr. Salihee would still be alive and with his family if in fact he had been more alert."

Vige's report did fault the unit for leaving the scene; saying it "couldn't have had a positive impact on the local populace."

He was right.

Mahmud Salman, 48, is a watch repairman whose shop was just beside Salihee's car.

"The Americans left the body in the car, and it seemed to us that that was cold-blooded," Salman said. "Watching it, based on my experience, when they left the body this way, it will further increase the resistance and the people's hatred of Americans."

Eyewitness Khalid Eider, 27, watched from his shop as soldiers left Salihee behind, slumped behind the wheel of his car. He says he hated the Americans then, "Not just for that day, but for what they are doing daily."

"We welcomed them, because we thought they would build our country," Eider said. "They have not built, but they have harmed us. They're proving daily that they're occupiers. Their objective is to get rid of us. They do not want to bring democracy in the wake of the dictator Saddam. I hope that Saddam and his entire dictatorship returns. He at least kills people far from our view."

A Brother's Investigation

Aymen Salihee, frustrated with the U.S. Army, did his own investigation. He interviewed witnesses, visited the morgue and photographed the bullet. He says that Vige's report, which he received several months later, is a cover-up.

"The American soldiers are protected by law and do whatever they like," Aymen Salihee said.

In particular, he said that Vige should have mentioned in his summary that Vige's own diagrams show Romero standing off to the side of the road, where he might not have been visible to someone coming up the street.

Vige's investigation included interviews with three Iraqi eyewitnesses; their names are redacted. Two of those accounts match what Iraqis told NPR: Yasser Salihee "stopped" his car, but the Americans fired on him anyhow.

One witness said the driver "was not paying attention" when Iraqi soldiers tried to stop him. Aymen Salihee -- and most of the neighborhood -- believes his brother did stop.

For his part, Romero remains confident that he did the right thing, and not one of his fellow soldiers or commanders that NPR interviewed has questioned his judgment on that day.

"I think about it every once in awhile," he said. "But I can live with myself. I didn't murder the guy. I could have blatantly shot the guy. I don't know how I would have lived with myself. He has a family, you know? But I can come to terms with it because I did what I needed to do at the time."

Recalibrating the Rules of War

According to Maj. John Dunlap, the chief law officer for the 256th, the brigade investigated about 40 serious incidents involving injury or death to innocent Iraqi citizens during its year in Iraq. There is no way of comparing that number with the record of other units since, at the time, most didn't release those figures.

The most publicized 256th case was the wounding of Italian journalist Giuliana Sgrena. She had just been released from captivity as a hostage and was being transported to the Baghdad airport when American soldiers fired on the convoy, killing an Italian intelligence officer. In another case, a family in a white pickup was shot, killing the parents. In late August, an Iraqi Reuters soundman was killed and a cameraman was shot.

In all cases, the 256th found that the rules of engagement were properly followed and no disciplinary action was taken.

"You don't want to create an environment where every time a soldier pulls the trigger, they think there's going to be an investigation," Dunlap said. He said it's important to understand that these investigations were carried out only to determine whether the rules of engagement were followed and to capture lessons learned. They were not criminal investigations.

"Soldiers were called upon to make decisions on a daily basis in snap seconds," Dunlap said. "And we did not want to create an environment where soldiers thought they were going to be second-guessed and prosecuted for making decisions that would save their life. Rule number one is to come home alive."

Today in Iraq, commanders are trying to recalibrate the rules of engagement, recognizing that to put the protection of U.S. forces above all else may interfere with winning the war. Ret. Gen. Andrew Krepinevich is with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessment.

"When you see some of these unintentional killings that still fall within the rules of engagement, it may not be the fault of the soldier, but at the end of the day, it's losing a battle," Krepinevich said. It's losing a battle for the center of gravity in this war, which is the population, the people of Iraq."

Aftermath

But the impact these killings have is not just on Iraqi civilians. Platoon Sgt. David Reith, who was on the street that day, says the memories of killing innocents, like Yasser Salihee, will always be with him.

"It happens a lot," Reith said. "I think it was one of the hardest things I had to deal with, physically shooting somebody, not a bad person. You know he just did the wrong thing. That's the hardest thing to deal with."

Another soldier in the 256th, who didn't want to be identified for fear of retaliation from command, says he is still trying to cope with killing noncombatants.

"It's a real hard situation to face. You know, sometimes you'll be in a firefight with two people and there's hundreds of people around them, which happened to myself and Sgt. Romero. … There's times when I felt I couldn't take being involved in one more innocent civilian being killed. You know, it tears you up inside every time it happens. And I still don't deal with it. You know I've dreamed of being in the military since I was a little kid, like a lot of little boys, but honestly, I'm ashamed of everything that went on over there."

But Vige, the man who investigated the Salihee shooting, says the nature of the war in Iraq makes close-call shootings like Salihee's inevitable.

"Now we can go back and we could hash it out from now until the end of time. It's not going to change that this guy is dead," Vige said. "If he would have maintained full situational awareness, he would still be alive."

"That's part of the bad part of war," Vige added. "Innocent people -- children, women, fathers, mothers, daughters -- are going to die. That's what war is all about. Can't change it."

In the aftermath of this shooting, the lives of those closest to Romero and Salihee have changed profoundly.

Romero remains in prison until August. He was convicted of possession and distribution of drugs. He has maintained his innocence and is appealing his case. He doesn't know what the future holds.

"I would probably go back to Iraq as a civilian contractor or I was going to teach at sniper school for the National Guard," he said from his prison cell. "But with the charges I have on me, I don't know what I'm going to do ... I've spent 12 years of my life in the military so I don't know what I'm going to do."

Aymen Salihee, the victim's brother, went to Mecca with his grieving parents, where he met foreign fighters from Tunisia and Pakistan. He turned down offers to avenge his brother's death. Iraqis should fight their own wars, he says, including the one against U.S. soldiers. But he doesn't want to join the fight.

"I'd like to get out of this f----ing place, because I hate this place. I just lost everything. My future is not here," Aymen said.

Dr. Wazzan is raising her daughter and coming to terms with her husband’s death. Yasser, she says, is at peace.

"I think that he is very happy now, because I saw him many times in my dreams, in paradise," Wazzan said. "He is with me and Danya everywhere I go."

In July 2005, the U.S. Army began tracking the deaths of Iraqis killed at U.S. checkpoints or shot by U.S. convoys. In February, Lt. Gen. Peter Chiarelli, the commander of day-to-day operations in Iraq, said preventing such deaths is a priority. The number of these types of shootings has dropped from an average of one a day in 2005 to an average of one per week.

Produced by NPR's Emily Ochsenschlager.

Independent journalist Phillip Robertson, in "Salon" magazine, was the first to write about Joe Romero. NPR acknowledges that his identification of Romero contributed to this story.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.