Vicky Myrick from Hope Mills, North Carolina, remembered the first time she saw her doctor.

“He immediately said, ‘the biopsy is not necessary. I’m 99% sure you have ALS,’” she recalled.

ALS is a neurodegenerative disease that impacts the motor neurons in the brain, the wires that connect the brain to the muscles throughout the body. It’s disabling and life-shortening, with no known cure. Myrick’s friends first noticed her foot drop in March 2024 — her difficulty lifting her foot caused an audible slap when she walked.

Now, the disease has progressed so that there’s a pain “like a dull toothache” in her leg, her voice is changing, and she is constantly tired.

As scary as it may be, Myrick is staying hopeful. Her doctor, Dr. Richard Bedlack, will make sure of that. He is a neurologist and the director of the Duke ALS clinic. To him, boosting hope is more than just a kindness. He believes that if he can foster hope in his patients, then he can impact their outcomes with the disease for the better.

“I’ve worked on this disease almost every single day, almost every single night, almost every single weekend,” he said. “I haven’t found a way to fix it yet, but I have found something that I think helps. It’s called hope.”

Foregrounding hope in ALS treatment is a radical practice given the degenerative nature of the illness. But, these conversations inspire Bedlack’s patients, and in turn inspire him. Knowing the desires of his patients helps him serve them better, and keeps his emotional tank full.

One way that he boosts hope is by wearing fabulous outfits. It’s a part of his philosophy, which he calls “stitching strength.” It keeps him upbeat. It’s also an icebreaker for nervous patients, who can’t help but comment on his eye-catching style.

The day that Bedlack saw Vicky Myrick in the clinic, his outfit was ‘70s inspired: floral shirt with a flared collar, over flared jeans, with a clay-colored jacket. Knowing who she was meeting, Myrick dressed up too. She wore a colorful blouse and special silver sandals, which she wears without the usual brace that cradles her affected foot. She had on a touch of red lipstick.

“I’m trying to keep up with Dr. Bedlack,” she smiled.

The Science of Hope

Across many diseases, having hope is correlated to better quality and satisfaction with life, from cancer patients, heart transplant recipients, and those in acute medical rehabilitation. Bedlack said that more hopeful people have different patterns of brain and gene activation; they have less inflammation; they engage in healthier behaviors, like eating well, exercising, and avoiding smoking and alcohol; they live longer.

“It’s hardly ever talked about in medicine,” said Bedlack. “I don’t know why it’s not a whole class in medical school.”

Not many studies have been conducted on how hope impacts people living with ALS, according to an article authored by Bedlack. He endeavors to change that. In five clinics, including the Duke ALS clinic and the ALS clinic at the University Virginia, doctors are testing whether speaking about hope with his patients can cause measurable impacts on their health.

Bedlack says that Duke’s Parkinson’s disease clinic, and a pediatric and general neurology clinic will also enroll patients in the data-gathering process which he designed. After two years of data collection, he hopes that the data from this program will be promising enough to design a formal trial.

Hope is more than a mushy feeling…

…it’s a cognitive construct, according to Medical Psychologist Shir Galin, who works with people who suffer from chronic illness and their caregivers. She authored a study that showed that people with ALS who were hopeful had greater satisfaction with life.

Hope theory was defined by the psychologist Charles Snyder in 1991. It says that hope has two defining features. Galin explained that one is pathways: “You can see the way to have a better future.” The other, she said, is agency, “which means that the person can see himself as the generator of the ways for a better future.”

This makes it distinct from other feelings like optimism, which, Galin says, can sometimes manifest as rose colored glasses, where people are positive in a way that is disconnected from reality. On the other hand, people can feel hopeful even in dire situations, because it is connected to actionalizable plans.

Hope takes work and practice, Galin says. In some ways, that’s what Bedlack is training with his patients.

In his project, he first measures his patient’s baseline satisfaction with life and baseline hope scores. For one group of his patients, he will leave it there, moving on to the rest of the appointment. But for others, he will ask them questions about hope. Over a course of many visits, he will repeat the same measurements with the same groups. Eventually, he expects to see the satisfaction with life and hope scores rise significantly more in the group that got to reflect about hope compared to the other patients who didn’t. And, maybe their medical outcomes will improve significantly more, too.

Bedlack asks about hope by going through two questionnaires. At the end of this stage of the project, he hopes to pick one to test in a clinical trial setting.

“Tell me two or three things that you’re hopeful about today”

In one, he asks the patients to name three things they are hopeful about. He says that very rarely did people say that they hoped to be cured.

“We hear very specific things that people want to accomplish, and now that we know about those things, we can personalize our approach to their care," Beldack said.

Commonly, people respond about a concrete milestone. For example, they might want to make it to their grandson’s graduation. Bedlack is therefore able to ask concrete follow-ups that support the patient towards their goal, such as: “Based on your disability, what kind of travel are we going to have to try to help you arrange? Where are you going to stay?” or “How are we going to get you equipment that can match with that access?”

Turbocharged Living

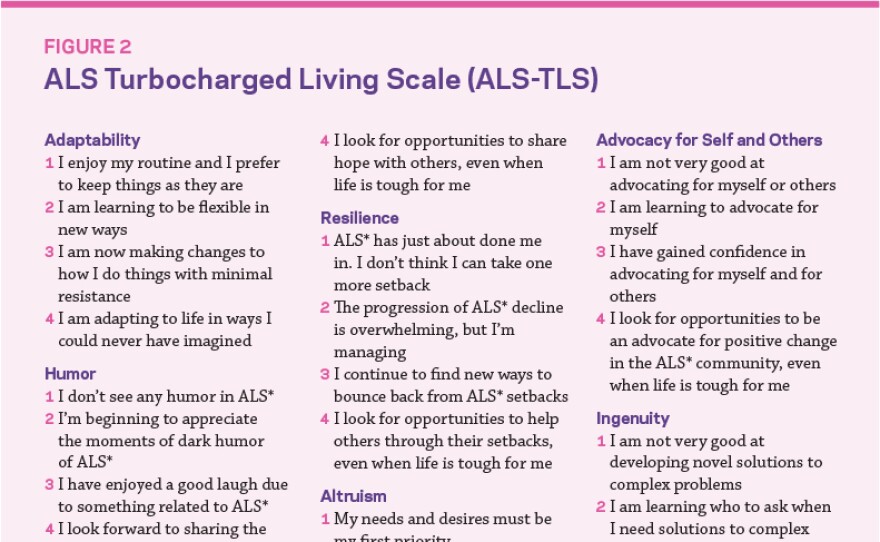

The second questionnaire that Bedlack asks was originally developed by the late James Plews-Ogan, a pediatrician at the University of Virginia who lived with ALS.

In an article for the University of Notre Dame’s Institute for Social Concerns, Plews-Ogan and his wife, Margaret Plews-Ogan, co-write that the progression of ALS is usually recorded by a scale that marks decline. In response, they wondered, “What if we began tracking ALS with a companion scale that documents progressive growth?”

Thus, the turbocharged living scale. It asks about the immutable parts of a person with ALS, including their sense of humor, altruism, and fierceness.

For Bedlack, this tool is a way to invite discussion and boost a person’s self-perception. Instead of handing the patients a clipboard and pen, he reads out the scale and uses it as a prompt.

“If they say, ‘Oh, humor is one of my strong suits,’ I say, ‘Well, tell me more, tell me a joke,’” said Bedlack. “You want to be able to really focus on… getting patients and families to talk about these qualities.”

Connecting with his patients in this way has allowed Bedlack to keep practicing after 25 years, in a field of medicine which can otherwise be grim.

As a medical psychologist, Shir Galin said that the fact that there’s no cure to ALS can undermine a doctor’s willingness to engage with patients meaningfully. “They become stiff, and it's harder for them to treat these patients,” she said.

But, talking about hope has made Bedlack a resilient doctor, too. “I see people beat ALS spiritually all the time by not letting it change the best parts of them,” he said.