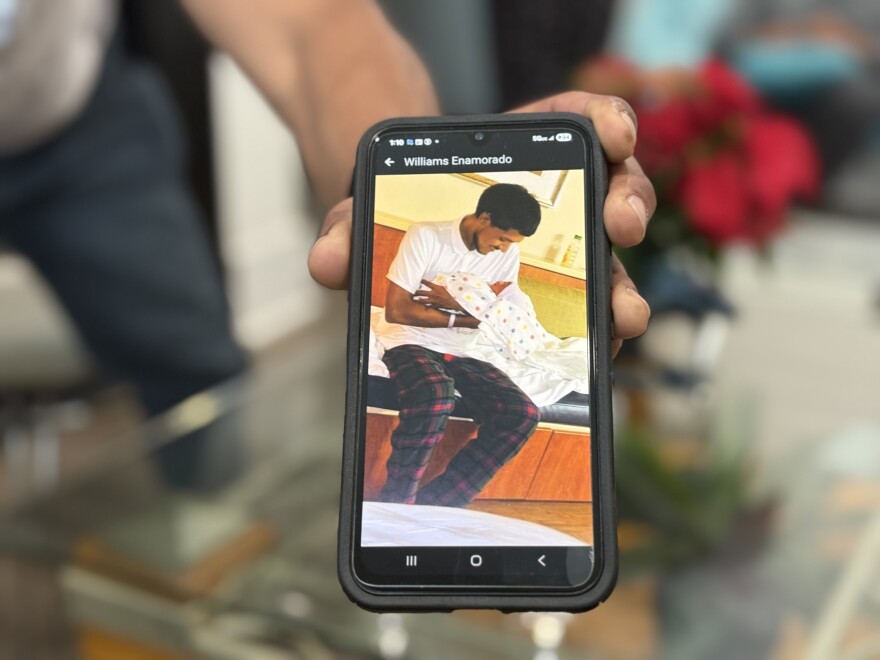

A Charlotte family says their son — a 27-year-old Honduran man with end-stage renal failure — was denied dialysis and pressured into signing a voluntary deportation order after being detained during last month's immigration operation known as "Charlotte's Web." Federal immigration officials deny the allegation.

An attorney for Williams Javier Toro Enamorado said his client remains in ICE custody as of Monday, and that after he raised concerns about the officers' alleged actions, ICE agreed not to enforce the voluntary deportation order and to allow Enamorado's case to go before a judge.

The family says they’re now worried about his health and fear what could happen if he’s sent to a country with far more limited access to dialysis.

A call from 360 miles away

Inside a small living room in north Charlotte, the blinds were closed and the curtains drawn. A family huddled together on a couch while a baby rocked and chirped beside them.

Above them hung a framed image of George Washington crossing the Delaware, the American flag billowing in the wind.

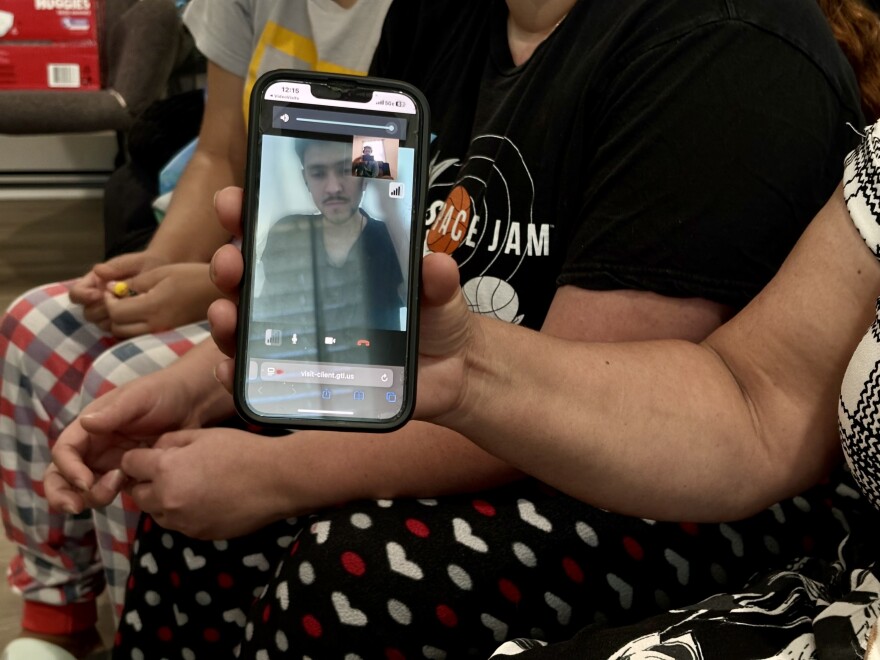

They leaned around a cell phone, straining to hear Enamorado through heavy static from more than 360 miles away inside ICE detention facility in Folkston, Georgia. He was taken there after federal immigration agents stopped him on Nov. 19 while he was driving to a routine dialysis appointment.

"William? Te escucha?" his mother asked as his sister tried to refill his phone account before the call dropped.

Enamorado has end-stage renal failure and needs nearly five-hour-long dialysis sessions three times a week. Missing an appointment can cause serious health problems that manifest within hours or days — including heart attack and death.

But Enamorado said that after immigration officers stopped him, they put him in a van and transported him more than five hours away without treatment. By the time he arrived in Georgia, he said his feet were swollen and his stomach felt sick.

"I wanted them to take me to the hospital the day I came here," he said through an interpreter, "but they told me no."

The next day, he said officers took him into a room and told him something worse — that he wouldn't receive dialysis unless he signed a voluntary order for deportation.

"I told the officer if they give me dialysis, I'll stay and fight my case, because dialysis is life or death," he said. But the officers told him no, he said, telling him, "If you want to leave, sign. If not, you're going to die here."

Thinking about his newborn son and family — and how he had no way to contact them because he didn't have their phone numbers memorized — Enamorado signed. Only then, he said, was he taken to a nearby hospital for a shortened dialysis session.

Attorney calls the account "classic duress"

Immigration attorney Jeremy McKinney took on Enamorado's case after being contacted by a local immigration advocacy group. He said the account, if true, amounted to "classic duress" and could raise "a whole variety of potential torts" and legal issues.

In a statement to WFAE, the Department of Homeland Security called Enamorado a "criminal illegal alien," citing past arrests for cocaine, marijuana and other "lethal drugs."

But McKinney said Enamorado has never been charged with possession of anything beyond a small amount of marijuana when he was 18. WFAE could not locate criminal records consistent with the government's statement.

DHS also said Enamorado "chose a voluntary deportation," and that any allegation that ICE intentionally withheld treatment to pressure him is false.

Even still, McKinney said DHS has since told him it will not enforce the voluntary deportation order and will allow the case to go before a judge in January.

McKinney said he believed Enamorado was eligible for and should be granted a green card. Until then, Enamorado's family worries he hasn't been getting full dialysis sessions while in custody, and that officers haven't been giving him his proper prescription medications.

'We came here to work and nothing more'

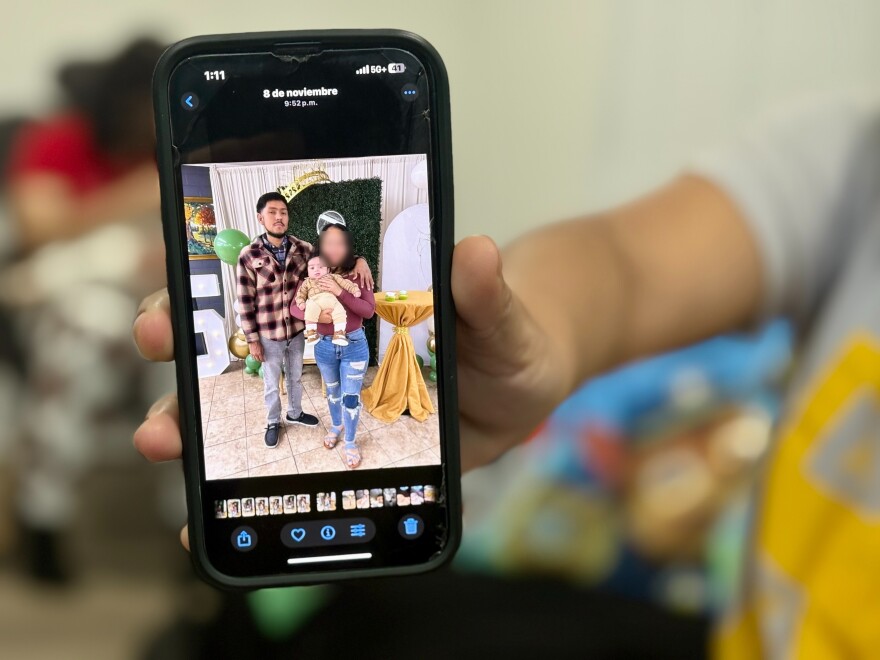

Back at the home, Enamorado's stepfather held the phone above Enamorado's 3-month-old baby, who smiled at his father on the screen.

His family said Enamorado hadn't been working in recent months. He spent most of his time at home with his child or going to dialysis, all while his medical bills were mounting.

The family said he came to the U.S. a decade ago by himself at 17 years old, seeking health care. The rest of the family followed, hoping to escape poverty and gang violence in Honduras and build a life here.

It's why they hung the picture of George Washington on the wall.

"We came here to work and nothing more," his sister said through an interpreter. And even if America had taken her brother, she said her feelings toward the country hadn't changed.

"It has nothing to do with people's hearts," she said. "There are many good people who are supporting us. People from here."

Enamorado's stepfather, Mario, said he supports efforts to deport people who commit crimes, but said his stepson didn't fit that description.

"In this case, my son wasn't doing anything wrong," he said through an interpreter. "He was going to dialysis, essential for his life."

He said he would ask immigration officers to look inward — "because before we are immigrants, we are also humans. We feel just like them."

He turned back to the couch, where the family huddled around the cell phone. By then, the call had dropped — Enamorado's minutes were used up. So they added a few more dollars to the account and waited, hoping the screen would light up again with his face from 360 miles away.