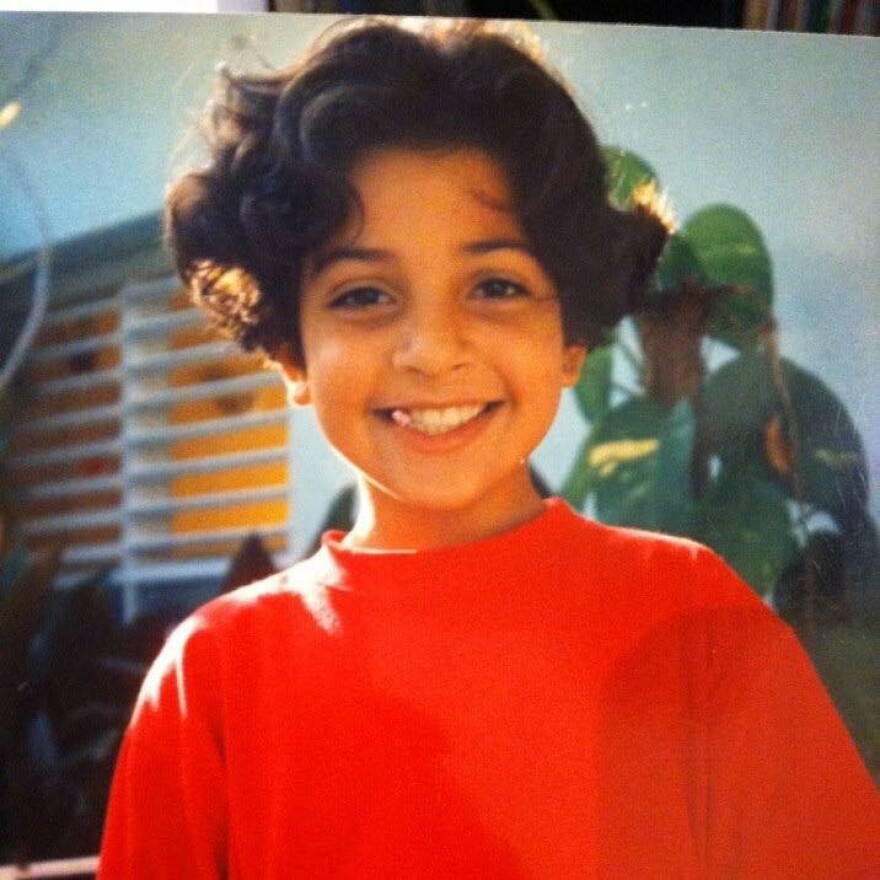

Ana Nuñez was nine years old before she ever stepped foot inside a grocery store or tasted an apple. Nuñez grew up in Cuba with intermittent access to food and medicine and abundant electricity shortages. In 1991 her father defected to the United States, and a couple years later the family followed.

But when nine-year-old Nuñez arrived in Florida, she did not speak any English and struggled in the classroom. Today she is a lawyer in Raleigh who practices criminal and immigration law.

She talks to host Frank Stasio about her journey from the suburbs of Havana to the Triangle. She also shares how the resilience she had to develop as a young girl helps her today in her high-stress job. She is a partner at Fay and Grafton law firm in Raleigh.

INTERVIEW HIGHLIGHTS

On being in Cuba in the late 80s and early 90s:

In history it's called the “special period,” but I just knew it as growing up — which was a period of scarcity in Cuba. There wasn't a lot because of Russia falling. So there was no gasoline. There were no dairy cows. Cubans went on a soy-based diet — that's not known — but there was a lot of soy yogurt, soy bean products and all that. And that was just how I grew up, because that's all I knew.

On how her parents thought about the “special period”:

I think professionally for them, it must have been very frustrating, because their work wasn't appreciated as some professional work is appreciated here in the United States. They were restricted in their travel. They couldn't go to conferences that they wanted to go to. They couldn't maybe talk about the ideas or theories they wanted to talk about at that time. So, I think professionally it must have been difficult for them at that time.

On adjusting to school in the U.S.:

It was frustrating, because in Cuba I was already in the fourth grade. And I didn't get to finish, so I had to essentially repeat all of fourth grade over. I was a year ahead, and now I was a year behind … And I didn't understand anything. The way math was taught was different. The way teachers engaged students was different … It was certainly a lot more regimented than what I was used to. In Cuba you had a lot of freedom as a student, even a young student.

On being an assistant public defender:

I was faced with the reality of the issues we have in our communities with poverty, with racism, with mistrust or distrust of police and law enforcement, and how all that substance abuse and how all these issues just show up in the courtroom every day ... Sometimes you would play social worker, sometimes you would play mom, when all you're trying to do is play attorney … I learned that as a lawyer in criminal court when you're representing indigent defendants, you have to understand that they have other issues going on. This isn't their number-one — sometimes it is their number one priority, but sometimes it's not — and it's your job to stop and listen and figure out where they're at and try to help them the best way that you can.

I was very privileged in how I came into the United States. I had an opportunity to travel here and come here legally, like a lot of folks do not have.

On going back to Cuba:

I went to my old school. I went to my old house. I went to a bunch of places that I remembered. But it's different to see the country the way it is now, because it's so much better than what I remember. It's certainly progressed forward, and I think the people of Cuba are trying to move on — I guess that's the best way to put it — and I wish the whole world would move along with them.