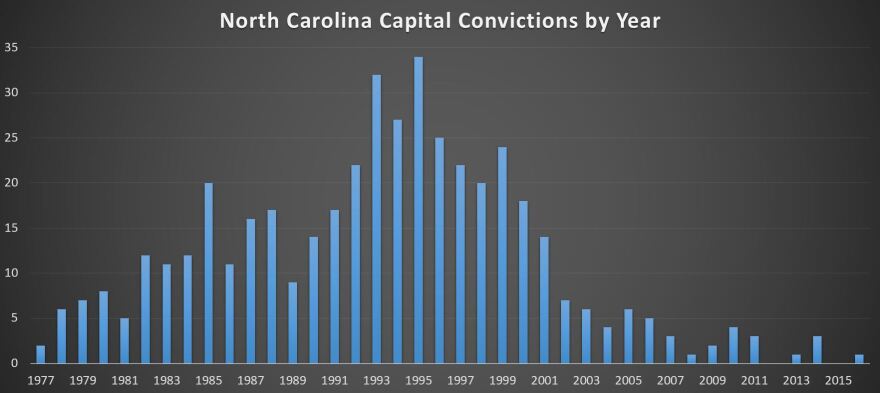

North Carolina has not executed a condemned prisoner since Samuel Flippen was put to death by lethal injection more than 10 years ago. Still, 16 convicted murderers have been sent to death row since then.

Some 147 prisoners, three of them women, sit on North Carolina's death row, awaiting a fate that might never come. All but 46 were convicted before 2001.

A court-ordered stay put a halt to executions in North Carolina. Litigation over the lethal injection protocol has dragged on and is still pending. A stay on executions has been continually in place since 2007.

This de facto moratorium, coupled with a decline in capital murder prosecutions, has stoked the death penalty debate. Plus, a recent rush to carry out executions in Arkansas has inflamed passions over this sensitive topic.

Opponents raise moral as well as practical arguments against the death penalty: It costs too much, it is subject to bias, the risk of executing a wrongfully convicted person is too high, and it violates constitutional provisions against cruel and unusual punishment. Proponents of the death penalty, however, often rely on emotionally powerful arguments about justice for victims who suffered horrible deaths and their bereft families.

For Jon Hardister, abolishing the death penalty just makes good common sense. Hardister, 34, is a conservative Republican state representative from Guilford County – and he's the House Majority Whip.

"It's actually more expensive to try to put somebody to death, or to try them, for a capital case than it is to sentence them to life in prison without parole," Hardister said.

Studies back up that claim.

Economist Philip Cook is a professor with Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy. He studied state data from 2005 to 2006 to determine what it cost North Carolina to try murder cases capitally.

"My estimate for both the trial courts and the appellate process was $11 million a year extra because the death penalty was being applied," said Cook.

Those heightened costs apply across the board, to prosecutors, the defense, and the courts.

Tom Maher compared the costs to the defense of capital trials against murder trials in which the death penalty was off the table. Maher is executive director of the North Carolina Office of Indigent Defense Services, or IDS, which was created by the General Assembly in 2000 to oversee public defender offices and to represent defendants facing the death penalty.

"Kind of a rule of thumb, the average case that's declared capital costs four times what the average first-degree murder case that's not capital. And so you're spending significantly more money and, you know, the outcomes are actually, oddly, not that much different," said Maher.

According to a 2015 fiscal year study, IDS found that over an eight-year period starting in 2007, the median cost of defending someone in a death penalty case was more than $60,000. The cost for non-death-penalty cases was $14,920 – less than one-quarter the cost – and more importantly, Maher said, having the death penalty on the table didn’t really affect the outcomes in plea deals.

"The number of people who plead guilty to second-degree murder facing a capital prosecution and the number who plead guilty to second-degree murder facing a non-capital prosecution are almost identical," said Maher.

Maher said he has tried to emphasize that point in meetings with District Attorneys, arguing, like Republican Representative Jon Hardister, that pursuing the death penalty just isn’t fiscally sensible.

Nobody knows better than Wake County District Attorney Lorrin Freeman how costly pursuing the death penalty can be for prosecutors' offices. Each case gets two prosecutors plus their legal assistants, jury selection is long and laborious and in addition to the guilt-innocence phase of the trial there’s a separate hearing on sentencing.

"Often that is all those prosecutors may be engaged in for three to four months out of a year and so again, these are cases – and they should be, it is our state's harshest punishment – but they are very resource intensive."

And for Freeman, a Democrat, it's clear that in Wake County there's a diminishing return on that investment. Wake County juries declined to come back with the death penalty in seven straight capital cases.

The last one was the Nathan Holden trial in February. Holden was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole after being convicted of killing his former in-laws and of attempting to murder his ex-wife.

"Again and again in cases in recent years what we are seeing is that ultimately the juries are not coming back with capital sentence verdicts," Freeman said.

Freeman said her office would be foolish not to acknowledge that trend and to have it inform the decisions they make about declaring cases capital.

However, Freeman is not saying she would stop pursuing the death penalty in appropriate cases.

"You know, as soon as a prosecutor is to say we've decided we wouldn’t pursue capital cases then there will be a case that the community and justice cries out for the imposition of the most serious punishment under the law."

For Jim O'Neill, Timothy McVeigh's 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City is just such a case.

"What's the appropriate punishment for killing 20 children? Life? To me that … is disproportionate," O’Neill said.

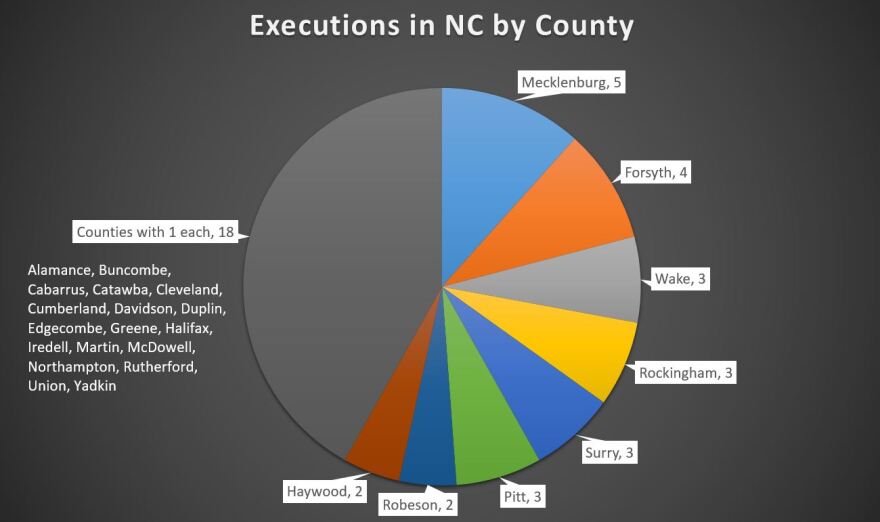

O'Neill is the Republican District Attorney in Forsyth County, a job he has held since 2009. He was an assistant D.A. in that office for 13 years prior.

Every time O'Neill enters or exits his office in Winston-Salem he passes a bulletin board adorned with photos and other mementos.

"And the reason I keep them out here is every morning I come in, I look at them and every evening when I leave I look at them too," he explained.

The photos are of victims in capital murder cases his office has handled – O'Neill recalls the victims' names and the tragic details from each of the cases. Bira Gaye, the Senegalese cab driver, working multiple jobs to send money to his homeland, shot in the back of his head; Robert Denning, an elderly, homebound man, killed in a home invasion along with a woman, Anne Magness, who, with her husband, Bill, was delivering food to Denning as a volunteer with Meals on Wheels; and Matthew Harding, a high school student working a summer job, who was robbed and shot coming out of the restaurant where he worked, he was then thrown into the trunk of a car.

O'Neill also keeps a quotation from the Bible on that bulletin board and on the wall inside his office. The quote comes from Genesis 9:6: "Whoso sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed: For in the image of God made he man."

For O'Neill, getting justice for these victims and their families means the cost of prosecuting death penalty cases is beside the point. Also, O'Neill pointed out, his office only pursues the death penalty in a small fraction of murder cases.

"In a place like Forsyth where we average maybe 20 murders a year there might be one case or two cases out of that 20 that is appropriate to be declared a capital case," he said.

Juries in O'Neill's district have not shown the same reluctance to recommend death in capital cases as have Wake County juries. In Forsyth County, juries sent defendants to death row three times between 2008 and 2014.

The jury results in Forsyth County mirror statewide polling trends. A 2015 High Point poll of 446 adults across the state found 63 percent favored execution as a punishment for the crime of murder.

In 2013, an Elon University poll found 61 percent of respondents favored the death penalty in murder cases – that from a telephone poll of 770 North Carolina residents. In 2010, the conservative organization Civitas conducted a poll of 600 registered voters in North Carolina and found 71 percent favored the death penalty.

Despite the polls, prosecutors are seeking capital punishment less frequently than in the past, not because of a decline in public support for the death penalty but because they can.

Prior to 2001, state prosecutors were bound by law to seek the death penalty in cases where at least one of several aggravating factors existed. Then the legislature changed all that.

"When I first started here and you had a defendant that met the statutory criteria to proceed capitally you had no choice you had to go forward. But in 2001 they gave prosecutors discretion and I think, obviously, what you saw was a drastic reduction in the number of cases that were prosecuted capitally and death verdicts that were coming back," Forsyth County D.A. Jim O'Neill said.

Once he determines a case is appropriate for the death penalty, O'Neill said he sits down with victims' families and carefully discusses the options – he makes sure they have the emotional fortitude to endure what could take years to resolve.

"It's not something that's going to happen in a year or two years if you're successful in terms of prosecuting it capitally but it will go on, of course, with litigation for years and years to come," he said.

Ben Streett and his family had that conversation with a previous Forsyth County D.A., Eric Saunders.

Streett's two-year-old niece, Britnie Nichole Hutton, was murdered in 1994 by her step-father Samuel Flippen.

"There was no question in our minds that this should have been a capital case because you're talking about, again, a defenseless, little two-year-old that was beaten for over a 20-minute period of time before she finally died."

Street said his family's commitment to seeking the ultimate punishment for his niece's killer never wavered, even though it would take a dozen years to happen.

On August 18th, 2006, the state put Samuel Flippen to death by lethal injection – the last execution to take place in North Carolina.