As Housing Booms, So Does Inequality

As the longest economic expansion in modern history heads into a new decade, pockets of people in North Carolina have seen their fortunes grow.

Unemployment levels are at historic lows, and workers with 401k or IRA retirement plans have added to their wealth. But a bleaker picture lies underneath the rosy numbers – one that shows many North Carolinians left out of the boom.

Low and moderate income families must work multiple jobs to keep their heads above water. Middle class workers have, for the most part, not seen a spike in their paychecks. Although inflation has stayed largely in check, housing costs in parts of the state have soared. That’s forcing middle class families into less desirable neighborhoods, working class families farther away from their jobs, and low income families at the brink of homelessness, or forced to live in decrepit – and dangerous – federal public housing.

Cities like Raleigh, Charlotte, Durham, and Greensboro now comprise the bulk of economic activity in the state. That has driven population trends toward North Carolina’s urban counties. Wake and Mecklenburg alone saw a larger population increase than 94 other counties across the rural parts of the state. As people consolidate, it causes property values in those areas to rise.

WUNC reporter Jason deBruyn and photographer Ben McKeown spent months exploring the trends. What emerged was a story of stark inequality that has left tens of thousands locked out of the American Dream, even as they can peer through its windows and see others living a vastly different reality.

Chapter 1: A Thriving Housing Market Leaves Some Behind

Adrian Brown walked through an empty house in North Durham on a recent December day. The clop-clop of his shoes echoed through the hallway as he strolled through each room. Brown, a Realtor with Inhabit Real Estate, knows the Triangle market. On that particular day, Brown showed a home in Colonial Village.

“Homes here tend to be a little more affordable and tend to have a lot of character, which a lot of people really like,” he said. “Which of course you see as soon as you walk in with the hardwood floors that run throughout the entire house.”

This 1,352 square-foot house had three bedrooms, one-and-a-half bathrooms and a modern kitchen.

“Good closets,” added Brown as he stepped into the third bedroom, which housed the half bathroom but sat on the opposite side of the house from the shower. “All the windows have been updated.”

The sellers bought the house in 2008 for $150,000, according to Durham County property records. Brown noted that was after renovations had already occurred. A decade later, they listed the property for $259,000, almost 75% more. It sold in three days for $281,000, according to county property records.

“I will say this type of house in this neighborhood, it was competitive,” said Brown.

This kind of scene is playing out across the region. The caveman advertising “We Buy Ugly Houses” has popped into mailboxes in neighborhoods from Apex to Zebulon. Even homeowners who weren’t necessarily thinking about a change have looked into the value of their property.

According to Triangle Multiple Listing Service data, the median sales price has increased by 50% since 2011, to $278,000. Homes now spend just 31 days on the market, on average, down from 126 days in 2011. The final sales price comes in above the asking price enough times that sellers now receive a full 98% of the original asking price, on average, one of the highest marks in recent history.

“We have way more buyers than we do sellers, which of course makes it great for sellers. Just makes it very competitive for buyers,” said Brown. “I do think people are recognizing that. Certainly the people who still want to buy something. And so they’ll make an adjustment. I mean this is a one and a half bathroom house; ideally, people want two bathrooms.”

While that reality means a certain segment of the population can’t afford all the amenities they want, there’s another segment of families who would love to have those problems.

“Housing is one of those areas where you’re just seeing a ratchet up of cost. For those who are doing well in the economy, that’s fine. But for those who are kind of in those jobs that don’t see a lot of pay increases, those people that are fighting for $15 an hour wages…those folks are being left behind.” – Henry McKoy, professor of finance at North Carolina Central University

Generally, housing is deemed affordable when it comprises no more than 30% of a household’s budget. For most metrics, that includes mortgage or rent plus utilities. According to the N.C. Housing Coalition, more than 25% of all households in the Triangle don’t meet that criteria. That means more than 170,000 households in Wake, Durham, Orange and Johnston counties face a cost burden to put a roof over their heads.

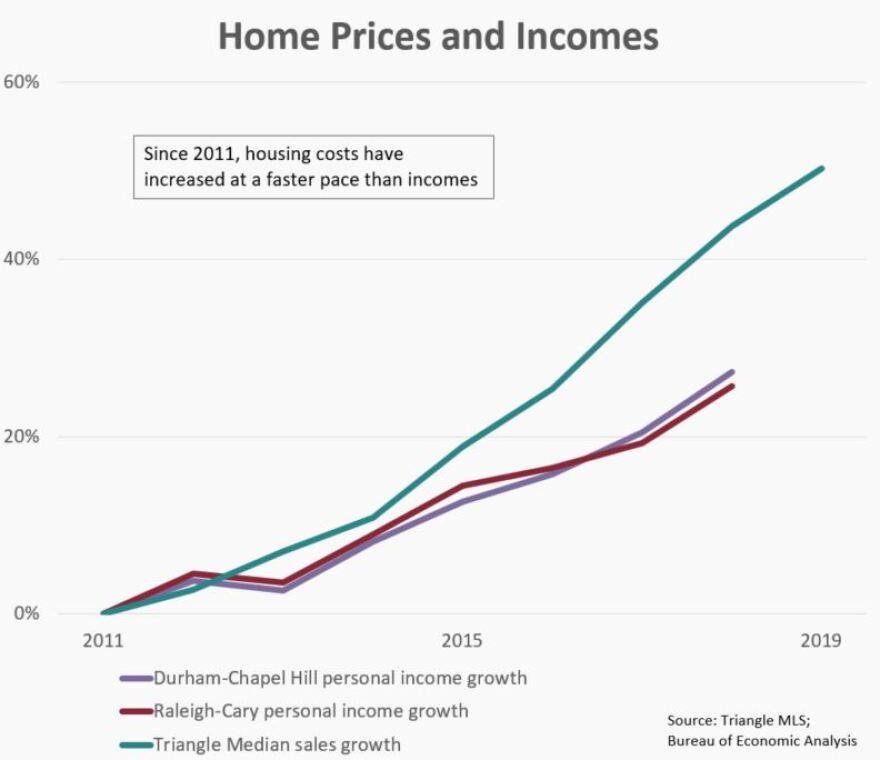

Housing Costs, Household Income Impact Crisis

It’s easy to look at housing costs as the culprit. And certainly it’s a contributing factor. But household incomes play an equally important role. After all, if income growth outpaces even a fast-growing market, households won’t feel a pinch.

“And so we have to have a real conversation about what’s happening with people and their incomes, upward mobility, job opportunities,” said McKoy.

In the Triangle, household incomes have increased by about 18% since 2011. That’s less than 3% each year during a time of massive economic expansion. For comparison, the S&P 500 stock market index increased by 158% in those years. The majority of economic gains have concentrated at the upper ends of the income spectrum, widening income inequality.

“If all the resources are going to the top, and none of them are staying at the bottom, then what does that mean for the future of society?” said McKoy. “And I think right now we are in some perilous times.”

McKoy’s sentiment is felt acutely at places like the Women’s Center of Wake County, where people like Renate Laredo have turned as a last resort. On a recent visit, she told a story of how she first saw her hours cut from a job at a discount store, before she lost that job altogether. That left her short on rent money.

“My landlord took me to court, and they wanted me out, and here I am,” she said as she sat in the office of the women’s shelter, which takes in women suffering from homelessness. The center has seen a noticeable uptick in need, according to Nora Robbins, the center’s development officer.

Laredo echoed the sentiment.

“It’s just tough being a single woman out here. And not having enough places to go,” said Laredo, an immigrant from Germany who moved to the United States in 1983. “If you lose your place today, and you can’t find an empty bed at a shelter, you’re pretty much out there in the cold.”

Of course, housing demand also plays a role in rising costs.

“Municipalities all over the country, they compete very aggressively to attract firms, and the hope is they’ll create this sort of demand for their city,” said Andra Ghent, an associate professor of finance at UNC’s Kenan Flagler School of Business.

By many metrics, Raleigh, Durham, Chapel Hill and other Triangle towns have succeeded in those efforts. The Raleigh and Durham-Chapel Hill metro unemployment rates dropped to as low as 3% by the end of 2019, down from rates above 9% in 2010, according to data from the N.C. Department of Commerce.

But employment alone doesn’t paint the fullest picture. One of the enduring truths about this protracted economic expansion is how little wages have grown, particularly at the lower and even middle income levels.

When companies do expand higher paying positions, they attract at least some of that talent from outside the region. City leaders generally agree those are desirable outcomes, but the question for local policy makers comes down to what happens to the existing residents who don’t directly benefit from those successes.

Triangle J Council of Governments advises policy makers on a range of civil issues, including housing. Perhaps ironically, council senior planner of community and economic development Erika Brown said she and her partner were in the process of looking for a home to buy themselves. Her professional conclusions about the hot housing market meshed exactly with what she experienced as she hunted for a home.

“And so starting to look at houses, I was realizing, ‘Wow, there’s really only a few that are really below $250,000,” she said. “Where they are, is usually not ideal. And then on top of that, the quality of those houses are not that great.”

New Residents And Cash Buyers Limit Options For Others

Brown says that realization, and the influx of talent coming in, creates issues for those already living in the Triangle.

“There’s a lot of folks who have higher incomes that are coming from outside of the region that are competing for those houses right now,” said Brown, adding that it’s not just the higher incomes that contribute to escalating prices. “On top of that, folks who are coming from out of the region who have properties that they sold to move here, they may have equity that they’re using for that cash-on-hand transaction. So that really limits first time homebuyers, younger property owners who maybe have student debt.”

In addition, the market has attracted cash-rich investors with even deeper pockets. Brown said investors’ market data shows they can sell housing stock for $300,000 or $350,000, so they know they can recoup their investment, even if they have to pay an extra $10,000 over what a buyer might offer.

“Investors have cash on hand, they can move quickly. That’s their job. Whereas me, I am just sort of trying to figure this out with, you know, a limited budget.”Erika Brown, Triangle J Council of Governments Senior Planner of Community and Economic Development

Chapter 2: Gentrification Brings More Whites To Minority Areas

On a warm and sunny late fall day, Wanda Morgan swept the last of the autumn’s leaves off her front porch. The brick on her house and front walkway was weathered, showing the home’s age, but also the quality of its foundation.

“I’ve lived here since 1959 when I was born,” said Morgan. “My mother and father built this house.”

She hasn’t lived here continuously; Morgan moved back to the house near Chavis Park in Raleigh to care for her mother, who is now in her late 90s.

“Being poor is (seen as) a crime. It’s not a crime, but it’s visualized as being a crime. So if you are poor, you are not worthy of being my neighbor. But they could be some of the best people in the world.”Rep. Yvonne Holley

Morgan’s house sits along South State Street, historically a majority black section of town. Now, it has become one of the many blocks in the south and east parts of the city going through changes. As Morgan stopped sweeping for a minute, she looked to her right where, not 50 yards away, stood two much larger houses under construction. Morgan didn’t know those new homeowners specifically, but said she has seen the effects of gentrification firsthand.

“When they buy these homes, they border them off,” she said. “They put up what they call ‘privacy fences.’ So that means we’re not coming out to you the neighbors, and the neighbors are not coming in to us.”

Morgan paused to reflect on what she had just said, and added that didn’t apply to every newcomer.

“I have noticed that working out here in my yard, or things like that, (a newcomer) will pass by and we speak to each other and might start up a conversation. But some of them don’t. Depends on I guess where they come from or who they are. But it’s like you don’t really know your neighbor. You know? That’s the big change.”

East and south Raleigh have a long history of black homeownership. But in the past decade, that has started to change. In the 14 Census tracts to the east and south of downtown Raleigh, the white population increased by 82% from 2010 to 2017, according to a WUNC analysis of Census population figures. During that same time, the non-white population increased by just 5%.

“It’s been rapid,” said State Representative and area resident Yvonne Holley. “It’s been rampant and rapid. It went from zero to 150. It didn’t happen with one or two houses.”

Holley lives in a historically black neighborhood off Glascock Street in the Oakwood area, a part of Raleigh that was among the first to gentrify. New people coming in isn’t a bad thing in and of itself, she said. But when it comes at the cost of displacing too many existing residents, it tears at the fabric of a neighborhood.

“So then you have a community here,” she said. “And then the community is fractured.”

Both Holley and Morgan said that gentrification doesn’t have to carry a negative connotation. After all, investing into a dilapidated property raises the value of all homes around it. But when it comes at the expense of the community in a neighborhood, or if it displaces residents – that’s when they take note.

“I see two sides to it,” Morgan said, as she leaned on her broom. “I see the improvement of the community. And I like diversity. I don’t have a problem with diversity. Just as long as, you know, it’s done in a respectful way, and you’re not trying to, I guess, downplay people or try to push them out where they don’t have anywhere to go.”

Over on Bragg Street, just a few turns from Morgan’s front porch, that’s exactly what makes some people nervous.

Tommy Pelzer and Stormi Bova sat outside of their rental units on the same warm autumn day that Morgan swept leaves from her porch. Bova said she has lived there longer than any of the other residents and acts sort of like the mayor of the complex. She doesn’t want to leave.

“I see two sides to it. I see the improvement of the community. And I like diversity… Just as long as it’s done in a respectful way.”Wanda Morgan

“I’m just very comfortable,” she said. “And if there’s any trouble, I go ahead and try to help my landlord get it straightened out. You know, help people out.”

But she’s reading the tea leaves. Just one block over, the intersection of East and Hoke streets isn’t recognizable from just a few years ago. Where once stood a row of abandoned houses and overgrown weeds, now stands modern homes with brightly colored front doors and green lawns.

“And I’m scared that they’re going to push us out next,” said Bova.

Pelzer worried that would likely mean only one place left for them to turn.

“The streets,” he said. “Is that what the answer is going to be? I’ll be in the streets homeless because of the simple reason that you can’t afford (rent). So we are getting pushed out, or bulldozed out.”

That’s exactly what Representative Holley fears as well. She said that when the middle class moves in, the lower class is forced out.

“What we saw on Bragg Street, there is no respect. We are here long enough for you to get out. How fast can you go? We are here to take this community over. We don’t want you in here because you are poverty,” Holley said.

It’s not an explicit effort to expunge a community of poverty, but Jesse McCoy, a lecturing fellow at Duke University’s Law School and supervising attorney for the Duke Law Civil Justice Clinic, said market forces can have the same effect.

“This is one of the few countries in the world that does not declare housing as a right. And so housing for us is a commodity that is going to be subject to the whims of supply and demand,” he said. “And unfortunately, when you look at it from a business perspective, then what happens is we essentially penalize those who are not able to keep up with the demand that we expect from pricing. So if you aren’t able to continuously pay your rent, for the term of your lease, we don’t really look to see why. We look to see, ‘You didn’t do it, so you have to be out’.”

Of course, Raleigh isn’t the only place to gentrify. Across the Triangle, Census tracts near the centers of Durham, Chapel Hill and other towns have become more affluent and white, while tracts farther away from the city centers have seen minority populations increase.

Stagnant wages exacerbate this divide. Stagnant wage growth has been one of the enduring legacies of the 2010s economic recovery. But while all racial groups experienced stagnation, black households have experienced it acutely.

The Census Bureau publishes household income by race by county. In its 2018 figures, the most recent available, there were 11 counties with black populations too low for the Census to make accurate estimates. Of the remaining 89 North Carolina counties, not a single one showed that black median household income was greater than white median household income. Furthermore, white household income sometimes outpaced that of their black neighbors significantly. In 11 counties, white median household income was more than double black median household income. In 60 counties, white families had a median income at least 50% higher than black families, and in 85 counties, the figure was at least 24% higher.

In a sign that the racial income gap has only widened, the growth of black median household incomes from 2011 to 2018 was higher than that of white families in only 38 counties.

“At the end of the day, we can’t have a real conversation about the issue of affordability of housing without having a real conversation about real wages,” said McKoy, the finance professor at North Carolina Central University.

He pointed directly at political decisions made by middle class America as a culprit for sustained inequality.

“Particularly middle income people say, ‘Well you know I don’t agree with this person’s philosophy. But hey! My 401k never looked better,’” he said. “And so it gives you this sense that there is a tradeoff. That you are willing to say that basically as long as I’m doing alright, or as I’m watching my resources increase, that I’m actually willing to turn a blind eye to what other folks are experiencing. And maybe I give the guy on the corner a dollar or two when I see him. Or maybe I still give money to my church. And maybe I make some donations. But some of the larger pieces. That’s where you see some of the disconnect.”

Chapter 3: For Those Struggling Economically, Housing Adds To Stress

Ernest Alston has the kind of warm and inviting smile that would put anyone at ease. He’s a Marine Corps veteran who sits and stands straight. Not at attention, exactly, but with his shoulders back. He had a post-military career as a truck driver, and claimed he could still back a long trailer down a narrow alley.

Now he spends his free time fishing, reading the Bible, and singing gospel songs like Amazing Grace. He broke out in tenor through the first stanza.

“That’s my testimony,” he said after he finished. “I was blind, but now I see.”

As a younger man, Alston struggled with depression and anxiety. Those illnesses led to drug abuse and homelessness. He cycled through shelters or rented rooms where he could.

“It’s bad being homeless,” he said. “It’s painful. I lost a lot of hope.”

The picture of homelessness to many in the middle class is that of a person sleeping in a tent or on a street corner. In truth, only about a quarter of those considered homeless are truly unsheltered, according to the N.C. Coalition to End Homelessness. The remaining 75% find beds in emergency shelters or transitional housing. While these places provide a roof, they’re often far from safe.

“You’re constantly on guard for one thing. You don’t know who’s sleeping next to you. You don’t know what the next person has on his mind. You don’t know if he has a disease, or if he’s ready to rob you.”Earnest Alston

A study by the National Institute of Mental Health found that nearly a quarter of individuals experiencing homelessness suffer from a severe mental illness, compared with just 6% of the American population as a whole. Nearly half of all those who experience homelessness show a history of a mental illness, and homelessness exacerbates mental stress.

“You can’t really relax. You have to keep your antennas up. Because if you don’t, you’ll get got,” said Alston. “Laying down with your pants under your head, because you’re scared to let them get too far from you.”

The Challenge of Counting Homeless Populations

The N.C. Coalition to End Homelessness estimated that 27,900 people across the state experienced some kind of homelessness in 2019. Although the group estimated that homelessness has decreased by 24% since 2010, it noted that rates have increased again for two straight years.

Housing costs are one driver of that recent trend. As values rise, landlords can charge more rent. As rents increase, it prices out more people. Data from the Administrative Office of the North Carolina Judicial Branch bear this out. Evictions spiked in the years directly after the recession, but fell sharply until 2016. Since then, however, eviction totals have flattened, or even increased slightly. There were more than 106,000 evictions in fiscal year 2019, according to courts data.

Three years ago, Alston caught a lifeline. He moved into an affordable housing unit operated by CASA, a nonprofit that provides access to stable, affordable housing for people who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless.

“CASA aims to serve people at the very bottom of the income spectrum,” said Jess Brandes the nonprofit’s senior director of real estate development. “Our typical tenant has a disability, has experienced homelessness or near homelessness, and earns usually less than $10,000 a year.”

From an organizational standpoint, the model is straightforward. CASA buys housing units, and rents them out at below market value rates. But that can present some challenges. As a nonprofit, it takes CASA time to line up financing to buy a new project. In a lukewarm housing market, that’s no problem and sellers would often work with them.

“But the market has really shifted in the last five or six years and those days are largely over,” said Brandes. “CASA is out there trying to compete in the market with out-of-state – sometimes out-of-the-country investors – who know that the Raleigh-Durham area is a hot market. And they are competing with cash offers and extremely quick closings on the properties. And it’s very difficult for us to compete in that market.”

Around the Triangle, city leaders are clear-eyed about the need for greater affordability. Newly elected Raleigh Mayor Mary-Ann Baldwin has called housing affordability her “moonshot,” and has said the city will put an affordable housing bond on an upcoming ballot. In Durham, Mayor Steve Schewel lobbied hard for the $95 million bond that passed in 2019.

“If I walked right now from City Hall down to Five Points, I would pass someone or maybe two people who are homeless, and who ask me for money,” said Schewel. “The chances are 25% that someone would also come up to me and say, ‘Mayor Schewel, I can’t pay my rent in Durham anymore. The price of my rent has gone up so much that I’m going to have to move’.”

A big driver of unaffordability is that Durham – and the Triangle region – has grown its employment base and raised the standard of living for many. “But the problem is, 20% of the people who live in Durham, do not share in our newfound prosperity,” said Schewel. “And the question is, can we make the city we love a city for all? That’s our challenge.”

As options diminish for those at the bottom end of the income spectrum, it means they must accept lower standards of living. While public housing operates largely separate from the private housing market, its forces can affect public housing units. After all, if public housing residents were able to afford market rent, they likely would.

In Durham, residents of McDougald Terrace, the oldest and largest Durham Housing Authority property, are feeling those effects acutely. More than 200 families were evacuated in early January because of elevated carbon monoxide levels, and residents detailed putrid living conditions including sewage backed up into tubs, mold growth simply painted over, and cockroach infestations.

The Durham Housing Authority receives funding from Housing and Urban Development, a federal department. Although funding comes from Washington, residents often look to local governments for help. In Durham, the bond will help fund $160 million to deal with the affordable housing crisis, including $60 million for the redevelopment of DHA projects.

“As people in Durham know, our Durham Housing Authority units are very old and many of them are just simply crumbling,” said Schewel. “We’re not getting the support from the federal government that used to come in order to keep those even basically maintained. We have units that are permanently out of service because of mold in the Durham Housing Authority communities.”

Estimates show that across the nation, cities lose 10,000 to 15,000 units per year due to disrepair and lack of HUD funding.

Looking back at evictions, early warning signs indicate they could increase more sharply in the coming years. Completed evictions have been up slightly in the past few years, but initial eviction filings have increased more sharply, according to court data. Initial filings for the 2019 fiscal year were 6.7% higher than initial filings in fiscal 2017, the data show.

“Durham is dealing with roughly about 900 eviction filings per month,” said Duke University’s Jesse McCoy. “That’s one out of every 28 Durham residents.”

Even if a family ultimately survives the initial filing and stays in their home, the fight can be costly.

“Things that for someone who is of moderate or affluent means might be a minor setback. These things could be a catastrophe to the low-income demographic,” McCoy said.

Durham County has bucked the recent trend of increasing initial filings, though data show they were up slightly from fiscal 2018 to 2019. McCoy said that Durham has many respectable landlords who work with tenants who fall behind on rent, or need repairs in their houses. But he added that doesn’t apply to everyone.

“And then we have another category that I have affectionately called the bad landlords,” he said. “They do everything from threatening to deport members of our undocumented community for complaining about habitability concerns. They discriminate on the basis of race as to who they are going to house and when. They know that they are operating places that are in deplorable conditions. And yet, still sit with a smile on their face and evict people for not paying them. As if a lease was only a one-way street.”

As property values skyrocket, McCoy said it becomes that much harder for even the good landlords to cater to a low-income renter. With increasing values comes an increasing tax burden and costs to make repairs.

“On top of that if a Tennessee or a Texas corporation, or even a Russian or a Chinese corporation comes and says, ‘Hey we understand you have some hardships with the upkeep of your property, we’ll buy all your units and cut you a check for $1 million, and you can go into the sunset.’ It’s going to be tempting!” McCoy said. “Even if you have the best intentions for the community that you serve.”

Chapter 4: YIMBYs, The Missing Middle, And The Future Of Affordable Housing

The plight of public-housing residents in Durham’s McDougald Terrace put the issues many low-income people face squarely in the headlines. Even so, the underlying societal truths that lead to sometimes deplorable or difficult living conditions for some often go largely unexamined.

But a recent dramatic work in Chapel Hill took affordable housing issues out of city council chambers and onto the stage

“Affordable Housing: The Musical” is the brainchild of Maggie West. It is set in the cleverly named fictional town of Church Mound, where a city council wrestles over what to do with a particular piece of property. Affluent – and largely white – characters call for the town to make it a park, or allow a private developer to make it a high rise, or any number of other uses, while poor “residents” – largely black – beg the council for affordable housing. The actors in the play – some played by individuals who have experienced homelessness themselves – described the roadblocks faced by those looking for places to lay their heads.

Throughout the musical, the affluent crowd offers some form of the same spiel: “We support the need for affordable housing, just not here, or now.”

The idea for the play didn’t come out of thin air. West, a former co-director of Chapel Hill’s Community Empowerment Fund, advocated for the Orange County housing bond in 2016. The Orange County Board of Commissioners considered putting a $10 million housing bond on the ballot at the same meeting in which it considered a $120 million bond for schools. The board approved the full school bond, but cut the housing bond in half, to $5 million.

“We had 20 people there who were either homeless, or formerly homeless, sharing their stories who left just devastated. And I think experiencing that difficulty of getting the connection to happen from the commissioners who are elected to serve these folks and the three minutes at the microphone to share your story in a way that folks can really connect, and that disconnect really inspired the idea to turn that into a bigger artistic rendition.”Maggie West, former co-director of Chapel Hill’s Community Empowerment Fund

Local land use and zoning policies can dramatically affect housing affordability, especially zoning that prioritizes single-family detached housing, or that restrict homeowners’ abilities to make additions like mother-in-law suites not connected to the main house, or put duplexes and triplexes in neighborhoods of single-family homes.

Almost always, these policies don’t seem to be discriminatory on their face, and yet that’s the effect. One detached house on one plot of land for one family is the most expensive use of residential land. It not only drives up the costs for that parcel, but also eats up swaths of land quickly. A one-quarter acre property might not seem big, but when multiplied by the thousands of families in the Triangle who live in that setup, it will quickly take up much of the residential land nearest the jobs, pushing more affordable properties farther away.

Too often, however, any proposals that would help with affordability are met with fierce resistance from NIMBYs, or Not-In-My-Back-Yard residents. Like some of the characters in Church Mound, NIMBYs can be progressive and supportive of affordable housing in theory, but fight it in practice in their own neighborhoods.

This leaves the obvious question: If not here, where?

Across the country, people calling themselves YIMBYs, or Yes-In-My-Back-Yard, are speaking up. In Raleigh, Brent Woodcox is a YIMBY. He has worked in Republican political circles most of his career, and holds to a general philosophy of small government; he also argues that fewer zoning restrictions would lessen the burden for public housing.

“(Duplexes) will create more affordable housing in the private market, which will alleviate some of the burden that the public sector is currently trying to take on,” he said. He acknowledged that it might be a hard sell to some people, but that it’s one worth selling. “Human nature is to be afraid of change. And sometimes that’s good and serves us well, and sometimes it’s bad. Currently with our housing cost problem, it’s bad.”

Policy advocates have come to see the problem as a “missing middle.” Many cities allow for single-family detached housing, or large multi-family units like apartment complexes, but very little in between. In Raleigh, for instance, single-family detached housing accounts for 44% of units, and multifamily complexes account for 38%. Townhouses account for another 15% leaving just 1.3% for duplexes and 1.8% for mobile homes, according to Raleigh housing data reported to the N.C. General Assembly.

“If we’re defining better as more inclusive, more opportunity, more ability for people to buy in for the first time to a home, or to have rent that’s affordable compared to what they’re bringing in, then we’re going to need different types of housing.”Brent Woodcox

“And so that might mean that the duplex next to you has two families instead of the single family home that you’re used to. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that it has to change the character of the neighborhood. It could bring better character to the neighborhood, because more people are allowed to live there,” Woodcox added.

David Smith is the CEO of the Affordable Housing Institute, which consults with governments on housing policy. He put it more bluntly: “We have zoning which is actually contributing to making housing less affordable. And choking off the production of affordable housing,” he said. “The cities that have the absolute most difficult housing problems are the ones that have the most dominance of single family zoning.”

Advocates have argued that the growing problem of housing affordability does not apply just to those at the bottom of the income spectrum. Nurses, police officers, and other crucial foundational positions don’t come with the same salaries as investment bankers or tenured professors. And they have seen their options in the housing market diminish, to the point where may not be able to live in the communities they serve.

“Housing is where jobs go to sleep at night,” said Smith. “And affordable housing is where the foundational jobs go to sleep at night. And the foundational jobs are essential, but they don’t pay as much. And because of that, the employees who work in foundational jobs must live farther and farther away from the jobs that they have.”

In Durham, for example, more than half of the city’s 2,700 workers live outside the city limits. That includes 55% of police officers, and 75% of firefighters. In Raleigh, 62% of the city’s nearly 4,000 employees live outside the city limits.

Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean all of those employees live outside the city limits simply because they can’t afford prices inside the city. But it is also clear that housing prices play a role in where people choose to live.

By many accounts, Raleigh took a sharp turn toward more inclusive policies this year. Critics had lambasted the previous council for dragging its feet on this issue, and several candidates campaigned on a platform to take more forceful action against developers. New Mayor Mary-Ann Baldwin has called housing affordability her “moonshot.”

“I think we all want thoughtful growth that includes affordability,” said Council member Nicole Stewart. “The difference here, for me, is that if we focus on keeping things the way they are then we only keep them affordable for the people who already have them.”

In early January, the Raleigh City Council approved new rules around parking, cottage courts, and lifted a cap on height restrictions, all relatively simple changes that could encourage more affordability.

In Durham, voters approved a $95 million affordable housing bond that will likely help as many as 15,000 people find more secure housing.

And there’s more hope here than in some places. The Triangle area still has relatively low housing costs compared with other large metro areas around the nation. Smith, the housing consultant, said that if there’s a silver lining to the Triangle’s affordable housing situation, it’s that there is still time to adjust policies and create a more equitable future.

“So you have a real opportunity to avert the ghost of Christmas yet to come,” he said. “So my message to people in the Triangle is: Everybody who lives in the Triangle area has a stake in making sure the Triangle area has enough affordable housing that is well-located. If you think green space matters, you should think affordable housing matters. And you should devote as much attention and as much focus to making sure that we have a place for those people to live as you do to making sure that everyone has a place to recreate. It is everybody’s job.”