Updated at 10:30 a.m. ET Friday

When North Korea conducted its latest nuclear test, the ground trembled more than 3,000 miles away in western Kazakhstan. Recording the shaking was AS059, an automated seismic station that's part of a global network designed to detect underground nuclear explosions.

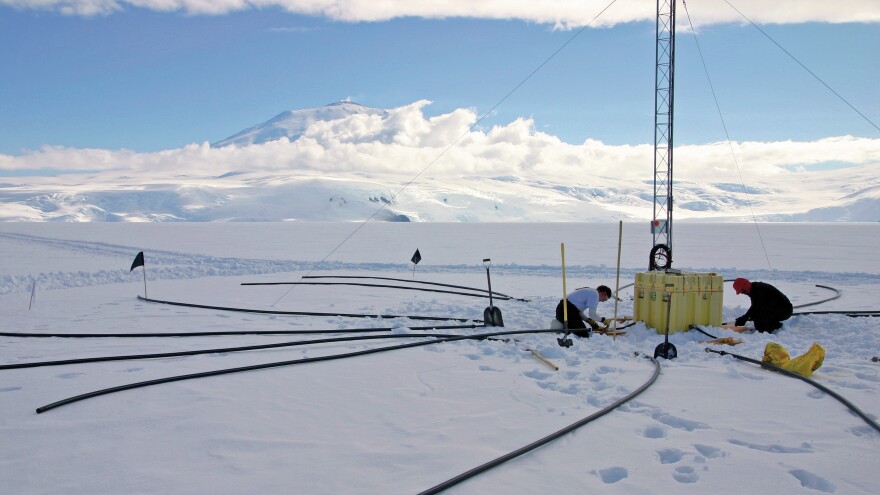

The network is run by the (CTBTO), a U.N.-affiliated group devoted to monitoring for illicit nuclear tests. While the test ban treaty itself is not yet in force, the United States and other nations fund the monitoring network.

This wasn't the first time a North Korean bomb shook AS059. The station has detected each of the North's six nuclear tests. But as the above chart shows, this test on Sept. 3 was far more powerful than previous ones. In fact, 36 of the CTBTO's seismic stations contributed to the initial analysis and more than 100 recorded the event, which the organization says was equivalent to a magnitude 6.1 earthquake. (The U.S. Geological Survey put the blast closer to 6.3 in magnitude.)

The shaking was also reportedly felt in China, and satellite photos show the explosion also triggered rock slides near the test site.

Independent estimates have put the test in the range of 120 kilotons to 160 kilotons. Friday, in an unusual move, the CTBTO provided it's own yield estimate of 100-600 kilotons (small uncertainties in the size of the shaking creates large uncertainties in the size of the bomb itself).

Update of #DPRK announced #NuclearTest yield estimates from different sources based on #CTBTO data & comparing previous tests. pic.twitter.com/GffiKAo2Wo

— Lassina Zerbo (@SinaZerbo) September 8, 2017

That's more consistent with a powerful thermonuclear weapon than with a conventional fission bomb. The North has claimed it conducted a hydrogen bomb test.

The organization continues to monitor for other signatures from the blast, including trace amounts of radionuclides that could have leaked from the site of the test. These radioactive gases could provide clues about the type of bomb that was tested. Weather models suggest that the gases could be detected in the coming days.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))