For the first time, scientists have created embryos that are a mix of human and monkey cells.

The embryos, described Thursday in the journal Cell, were created in part to try to find new ways to produce organs for people who need transplants, said the international team of scientists who collaborated in the work. But the research raises a variety of concerns.

"My first question is: Why?" said Kirstin Matthews, a fellow for science and technology at Rice University's Baker Institute. "I think the public is going to be concerned, and I am as well, that we're just kind of pushing forward with science without having a proper conversation about what we should or should not do."

Still, the scientists who conducted the research, and some other bioethicists defended the experiment.

"This is one of the major problems in medicine — organ transplantation," said Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, a professor in the Gene Expression Laboratory of the Salk Institute for Biological Sciences in La Jolla, Calif., and a co-author of the Cell study. "The demand for that is much higher than the supply."

"I don't see this type of research being ethically problematic," said Insoo Hyun, a bioethicist at Case Western Reserve University and Harvard University. "It's aimed at lofty humanitarian goals."

Thousands of people die every year in the United States waiting for an organ transplant, Hyun noted. So, in recent years, some researchers in the U.S. and beyond have been injecting human stem cells into sheep and pig embryos to see if they might eventually grow human organs in such animals for transplantation.

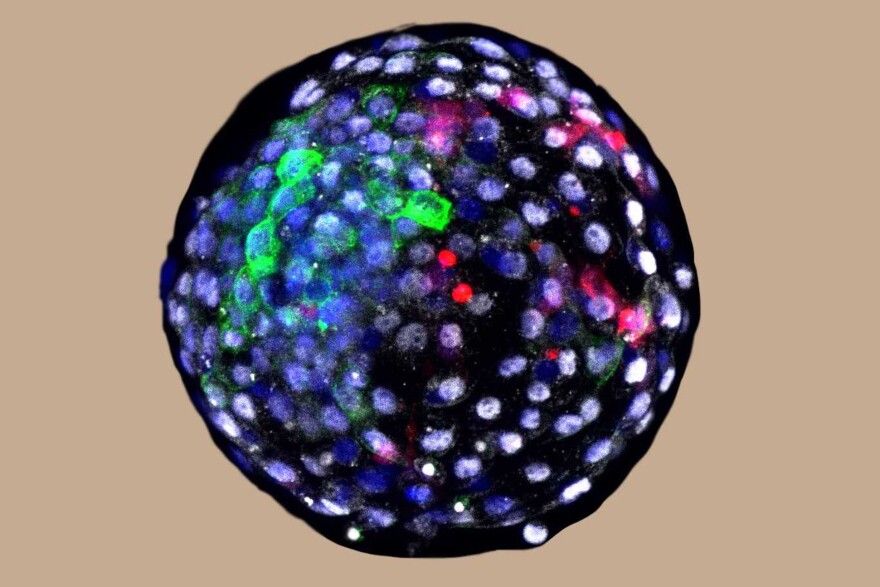

But so far, that approach hasn't worked. So Belmonte teamed up with scientists in China and elsewhere to try something different. The researchers injected 25 cells known as induced pluripotent stem cells from humans — commonly called iPS cells — into embryos from macaque monkeys, which are much more closely genetically related to humans than are sheep and pigs.

After one day, the researchers reported, they were able to detect human cells growing in 132 of the embryos and were able study the embryos for up to 19 days. That enabled the scientists to learn more about how animal cells and human cells communicate, an important step toward eventually helping researchers find new ways to grow organs for transplantation in other animals, Belmonte said.

"This knowledge will allow us to go back now and try to re-engineer these pathways that are successful for allowing appropriate development of human cells in these other animals," Belmonte told NPR. "We are very, very excited."

Such mixed-species embryos are known as chimeras, named for the fire-breathing creature from Greek mythology that is part lion, part goat and part snake.

"Our goal is not to generate any new organism, any monster," Belmonte said. "And we are not doing anything like that. We are trying to understand how cells from different organisms communicate with one another."

In addition, Belmonte said he hopes this kind of work could lead to new insights into early human development, aging and the underlying causes of cancer and other disease.

Some other scientists NPR spoke with agree the research could be useful.

"This work is an important step that provides very compelling evidence that someday when we understand fully what the process is we could make them develop into a heart or a kidney or lungs," said Dr. Jeffrey Platt, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Michigan, who is doing related experiments but was not involved in the new research.

But this type of scientific work and the possibilities it opens up raises serious questions for some ethicists. The biggest concern, they said, is that someone could try to take this work further and attempt to make a baby out of an embryo made this way. Specifically, the critics worry that human cells could become part of the developing brain of such an embryo — and of the brain of the resulting animal.

"Should it be regulated as human because it has a significant proportion of human cells in it? Or should it be regulated just as an animal? Or something else?" Rice University's Matthews said. "At what point are you taking something and using it for organs when it actually is starting to think and have logic?"

Another concern is that using human cells in this way could produce animals that have human sperm or eggs.

"Nobody really wants monkeys walking around with human eggs and human sperm inside them," said Hank Greely, a Stanford University bioethicist who co-wrote an article in the same issue of the journal that critiques the line of research while noting that this particular study was ethically done. "Because if a monkey with human sperm meets a monkey with human eggs, nobody wants a human embryo inside a monkey's uterus."

Belmonte acknowledges the ethical concerns. But he stresses that his team has no intention of trying to create animals with the part-human, part-monkey embryos, or even to try to grow human organs in such a closely related species. He said his team consulted closely with bioethicists, including Greely.

Greely said he hopes the work will spur a more general debate about how far scientists should be allowed to go with this kind of research.

"I don't think we're on the edge of beyond the Planet of the Apes. I think rogue scientists are few and far between. But they're not zero," Greely said. "So I do think it's an appropriate time for us to start thinking about, 'Should we ever let these go beyond a petri dish?' "

For several years, the National Institutes of Health has been weighing the idea of lifting a ban on funding for this kind of research but has been waiting for new guidelines, which are expected to come out next month, from the International Society for Stem Cell Research.

The notion of using organs from animals for transplants has also long raised concerns about spreading viruses from animals to humans. So, if the current research comes to fruition, steps would have to be taken to reduce that infection risk, scientists said, such as carefully sequestering animals used for that purpose and screening any organs used for transplantation.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))