Hip-hop may reign supreme in 2017, but it took several years of a digital revolution to shift dominance from music corporations, empower artists and prioritize the consumer before rap and R&B could bring home the gold.The crowning began with an unprecedented pocket of music history that saw hip-hop's pantheon of kings release this year's most anticipated compositions within a first quarter once written off as a dead zone on the album release calendar.

In March, Drake announced to the world that he would drop his anticipatedMore Life,a global cornucopia of a rap album the Canadian MC referred to as a "playlist." Three weeks later, Kendrick Lamar deployed an Instagram post along with the last bar of "The Heart Part IV" — a lyrical exhibition that shot venom towards naysayers, Donald Trump and unnamed rap peers — to announce the date for his eventual double-platinum triumph DAMN.

The preceding cold months were kept litby a high wattage of trap music. In January, Migos clamped a vice grip onto 2017 that has yet to loosen with the release of Culture. Future, revered by loyalists as the current king of trap, optimized February by serving fans his fifth (FUTURE)and sixth (HNDRXX) albums in succeeding weeks. The following month, Rick Ross offered his ninth and arguably finest composition Rather You Than Me.

But Ross' March release date wasn't selected by anyone employed by his label Maybach Music Group (MMG) or his distributor EPIC/Sony. Instead, its inspiration derived from someone much closer. "Way back in like August or September [of last year], Ross said that he wanted to put his next album out on his daughter's birthday," Kendell "Sav" Freeman, president of MMG, says. "That happened to be March 17."

The days of major labels dictating album releases or manipulating consumer interest are gone. The age-old formula of dropping an act's lead single, announcing a release date, then shipping said act off on a promo tour of free performances and media interviews is a dinosaur model. As artists increasingly drop albums with little or zero advance notice, the pre-announced release date is nearing extinction. "They're the enemy of creativity," as pre-eminent hip-hop producer Dr. Dre says in the HBO documentary The Defiant Ones.

This new level of sovereignty today's marquis rappers wield over their careers is a byproduct of the digital age and the on-demand culture resulting from it. Artists are increasingly charting unpredictable album rollouts based on their own strategic and creative self-interests. The trend may be the biggest disruptor to the old way of doing business since the emergence of Napster. With compact discs joining the music biz museum and streaming sites sterilizing the impact of piracy on the most "bootlegged" genre of music, hip-hop artists with leverage increasingly have more input on when and how their music is disseminated.

When Kendrick Lamar released his album on the second Friday in April, the determining factor for that date was simple: K Dot was invited to headline one of the world's biggest music festivals that same weekend.

"With Kendrick, he's going to work until we snatch [the album] out of his hands," says Terrence "Punch" Henderson, president of Top Dawg Entertainment, Lamar's boutique label. "But we had Coachella coming up and we didn't want to do a bunch of To Pimp A Butterfly songs."

"[Today] everyone is so savvy about what happens in the music business that you don't necessarily need that structured roll out that the label used to set up back in the day," says Henderson. "So if fans can get something refreshing from the artist, then it's a plus. But Kendrick is such a big artist that, at this point, we can minimize everything and it will still draw a gang of attention."

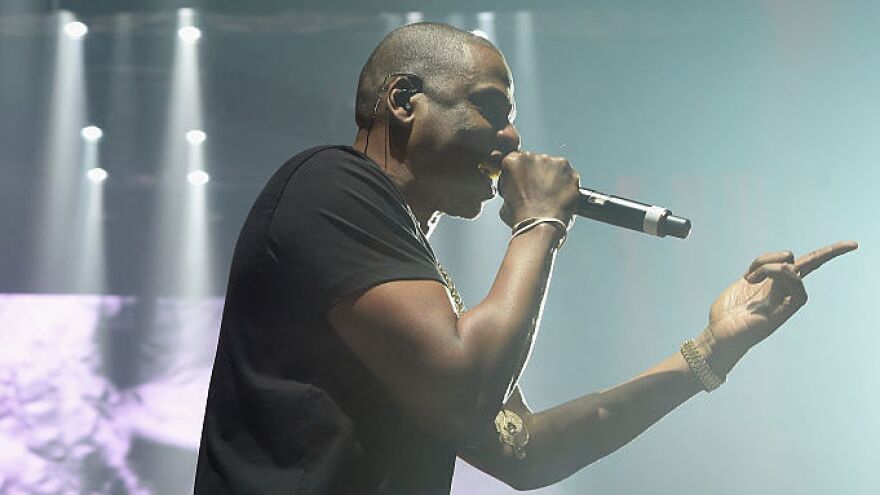

For such artists, less truly is more. To launch a national ad campaign three weeks before releasing his latest album, Jay-Z erected clandestine billboards in L.A. and New York featuring nothing more than the mysterious numerals 4:44. Like Lemonade, Beyonce's surprise visual album of 2016, 4:44 debuted exclusively on the streaming service Tidal.

After four years of starving his faithful of a follow-up to the gorgeous Channel Orange, Frank Ocean dropped two albums in August 2016: Endless, a 45-minute video album released exclusively through Apple Music, fulfilled Ocean's contract with Def Jam Records. One day later, he released a follow-up LP Blonde, which, due to his newly independent status, earned him an estimated $1 million in first-week profits, to the ire of his former label and its parent company, Universal Music Group.

But when an artist delivers an album may no longer be as important as how it's delivered, according to Ian Holder, the VP of A&R at SONY/ATV who signed Ocean to his BMI publishing deal in 2011.

"Everyone is realizing the power in a rollout," Holder, a 14-year industry vet, says. "The A-list artists are setting the tone by creating an experience for the consumer. It's up to us — the industry, community of artists, managers, executives — to create an experience for the consumer. Because they don't have a problem paying, they just don't want to feel shorted. Twenty years ago, we took the consumer for granted and we dictated what we were gonna give them and then charged what we wanted to charge them. That was standard back then."

But the game has been rearranged. Last year, streaming accounted for more than half of the revenue generated by recorded music for the first time ever, as Craig Marks reports in Vulture's recent look at the power of streaming playlists. Major streaming platforms — ranging from Spotify to Apple Music and YouTube to Pandora — combined to generate nearly $4 billion in 2016. Considering that hip-hop outsold country music in 1998, the year before the launch of Napster, there's an argument to be made that rap's dominance in consumption may have gone underestimated for years due to the increase of bootleg CDs and illegal MP3 sharing. (Nielsen ranked rap/R&B as the most popular genre for the first time in June.)

"[Hip-hop has] been the No. 1 genre probably for the last 20 years," Dina Marto, who formerly ran Island Def Jam's Atlanta office before starting Twelve Music & Studios, says. "But it's the way we now measure music that has changed. So now that we've had to change with the digital age and are allowing streaming to be a part of measurement, we're now realizing that urban culture has always set pop culture."

Before the impact of streaming, the fiscal interests of record companies governed album rollouts. Companies viewed the first quarter as infertile ground for hip-hop, offering the lowest volume of product. Five years ago, the only official rap releases in the first quarter of 2012 were debut studio albums by Diggy Simmons and Odd Future, and Rick Ross' Rich Forever, a mixtape pushed by Def Jam and MMG's distributor Warner Bros to become one of the most downloaded ever.

Inversely, labels have historically viewed the fourth quarter as rap's richest terrain. The latter 92 days of the year were reserved to hedge final fiscal sales by strategically releasing the largest acts during the holiday season, when music fans were most excited to purchase. "Another reason [record companies favored fourth quarters] was numbers tend to get inflated when released during the holidays," Holder says, explaining that year-end profits are the easiest to exaggerate. "During Christmas, numbers are, at times, doubled and even tripled."

Meanwhile, the Internet continues to make artists and consumers, respectively, more sophisticated and selective than ever. The on-demand boom has created the ability to quench consumer thirst at the touch of a button. The increase of media, and platforms on which to consume it, has stoked a ravenous hunger and shorter attention span in the market. Subsequently, the resulting insatiability has caused rap/R&B artists to evolve by utilizing shorter windows and fortifying new relationships with streaming companies such as Spotify and Soundcloud. This is a revolution of reciprocity between music act and fan.

Future is clearly a student of the times. He only gave a week's notice before dropping his first 2017 LP. He made history when, seven days after his self-titled album debuted atop the Billboard 200 album chart, he doubled down with another full-length LP that immediately shot to No. 1. By dropping two albums that were fully supported by his record label, he set a new industry precedent.

"Looking back on it, we couldn't have released these albums any other way," LaTrice Burnette, senior VP of marketing at Epic Records, says. "Future first mentioned that there would be a FUTURE HNDRXX album release years ago [and] both albums show a very different, but brilliant side of [him]." If Future can't decide which track should be his next hit, he can easily uncover which of his songs are streaming best. In fact, he and his team did just that to identify the hit potential of "Mask Off" before it went platinum in April. "One thing streaming has done is it's allowed you to actually measure the impact of your music," Future's manager Anthony Selah says. "I loved ["Mask Off"]; I thought it was dope. But I didn't know it was going to be [that] big. The future of music has a lot to do with experiential marketing and it has a lot to do with analyzing data and knowing what your consumers and fans like, and focusing on that."

This new day in the business of hip-hop music has loosened major-label dictatorship and empowered the artists, creatives, entrepreneurs and fans. Drake has the freedom to drop a playlist to be consumed as an album. Jay and Bey can stream their projects on their own platform. Ross is able to pinpoint his daughter's birth date for a new release. And a new generation of Soundcloud rappers has an audience at its fingertips. So what exactly is the role of a major record label in 2017?

"It's a collective effort," Freeman, who's worked in conjunction with EPIC since Ross signed with the label at the top of 2016, says. "It's everyone coming together to ensure the success of a record. The artist comes with their ideas and the label puts it in play. They're the engines."

Henderson agrees that it's a true partnership between TDE and Interscope Records, but he insists that the former has the first and final say. "Our relationship with the label is hand in hand. If someone has an original idea we'll incorporate it into what we're doing. That's if it's authentic. But our creative control is the most important thing. We never compromise that."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNzg0MDExMDEyMTYyMjc1MDE3NGVmMw004))